This is a story that was published in a Pakistani newspaper:

Dr Muhammad Aslam Khaki, advocate has asked [ ] to clarify a statement published by daily 'Jang' in her name on Nov 18 and tender an apology for it.

In a legal notice to [ ], the advocate said that the statement attributed to her whom he accused of being a model girl, was a serious violation of Islamic Laws. He said it hurt the sentiments of Muslims. [ ] has reportedly said that a Muslim woman should be [ ].

He said her statement was a threat to the honour and dignity of Muslim women. He said propagation of an idea contrary to Islamic teachings was an offence, carrying rigorous imprisonment and fine or both.

Dr Aslam said he would initiate legal proceedings against [ ] if she did not apologise within one week.

The notice was signed by 21 other advocates of Islamabad.

—

If you had to guess when this happened, which year would you date this to? It might be from a few years ago, about the trigger-happy mob that hounded Qandeel Baloch until her death (2016). It could possibly be criticism of Malala Yusufzai for questioning the utility of marriage (2021). It might even be a description of a scene from Zindagi Tamasha (2023), or the deeply foreboding short film Swipe (2020). It could be any story about the late, great Asma Jahangir. It sounds like it may even be from earlier this year, when a terrified woman was forced to apologise for being perceived as causing offence by wearing a dress that had the Arabic word for sweet printed on it.

This story is actually from 1989, when the model and actor Anita Ayub was asked to apologise for saying that women should also be allowed to have four husbands. (She said this in the context of women’s rights, her opinion of Pakistan’s male-dominated society, and in an interview to The Star, she offered fairly stereotypical views on marriage, believing that parents “should be given the mandate to select the spouse” and that “the wife should listen to her husband and the husband should see to it that he is not dominating. Understanding is must” while also criticising bigoted clerics and ‘mullahism’. She clearly contained multitudes.)

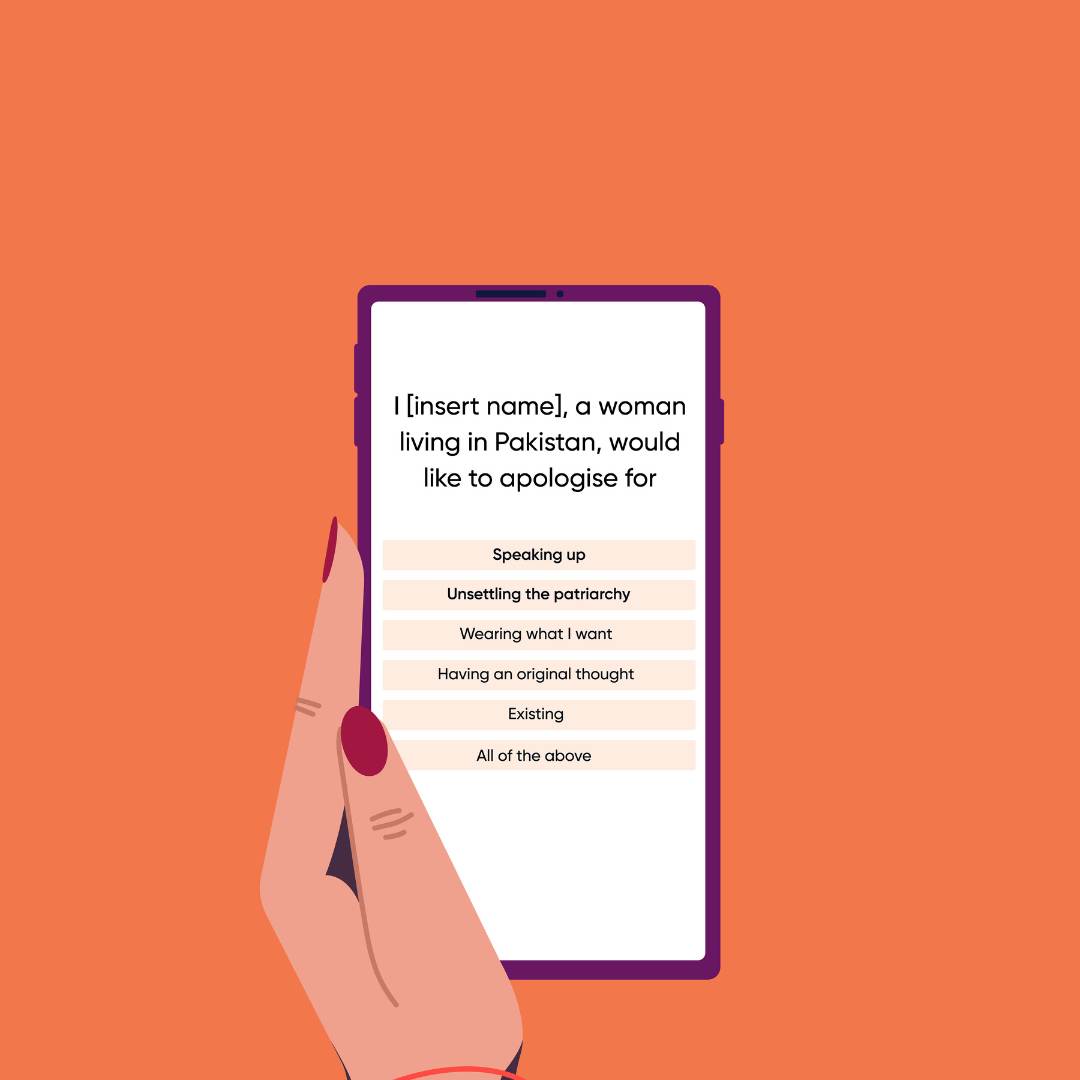

I left the name blank, because you can insert any woman’s name, depending on the era, and this would read like it had happened just last week. If there is something deeply disconcerting about watching a woman apologise, it is also familiar, because people are often made to apologise publicly in Pakistan for things that are perceived to have caused offence, not actually be offensive. When it comes to religion, of course, no one is spared, but women seem to face the brunt of the apology demanding machine. Sometimes these demands for apologies come attached to women who are considered ‘rebels’, but the reality is that women are expected to be forever penitent, forever apologising for offences past, present, future, and imaginary — and if they don’t comply, they can always be charged with defamation and forced to apologise.

For the last five years, while immersed in a project that has revolved around the life of a woman who was subjected to a trial by Pakistani society and the press, I have been constantly reminded that how much of what we see today are simply precedents set by the past. I’ve read hundreds of pages of newspapers from the 1960s and 1970s, and the headlines are often as jarring and ludicrous as the events of today. When people lament and yearn for an imagined past in which Pakistan was a tolerant place, I wonder how to make them understand that they are wrong. It is simply not true, as far too many people will insist, that this is not who we were. In fact, this is who many Pakistanis were: right-wing, ultra-right wing, conservative, ready to riot, even in the 1950s and 1960s and 1970s, decades that are valorised by too many Instagram accounts and black and white ads for hotels. But what has changed is that there is now a real prospect of imminent death. The notion that you could be killed in a shop or a cafe or outside your house for the idea to have caused offence, to be forced to apologise as if there is a literal knife to your throat, that the police would organise your apology tour as it just did in Lahore — this is what has changed. There is a long, horrible history of women being forced — nay, expected — to apologise, for an offence that only exists in people's imagination.

In February 1971, a representative for the People's Party had to tell the press that Nusrat Bhutto hadn't intended to offend people by criticising the practice of exchanging money for brides. “The Convener of Rawalpindi District Women’s Wing of the Pakistan People’s Party, Begum Habib Khan, said in Rawalpindi on Friday that Begum Nusrat Bhutto’s mention of the practice of receiving money for giving daughters in marriage in a TV programme was meant not only to insult rural population but only to condemn an un-Islamic and immoral custom still prevalent in the society,” reads a story published in The Pakistan Times on February 27, 1971. (For those of you following along at home, that’s 53 years ago). “… She pointed out that both Mr. Z.A. Bhutto and Begum Nusrat Bhutto belonged to village culture and said they could never think of insulting the village people. But, she said, it was the duty of every right thinking person to point out and condemn bad customs.”

The problem with being old, as I have unfortunately realised, is that not only have you seen this before, but that this script plays out with a depressing familiarity. Every generation has a story like this: a disconcerting tale of a woman being forced to apologise publicly. The first generation absorbs the incident with a sense of shock, and then it becomes acceptable, almost like a template; and it is this acceptance which should cause alarm. Sometimes, watching these videos and demands for apologies, I wonder if one is in a fever dream: has this happened before? Of course it has. Watching the video of the woman apologising in Lahore, I was reminded of something that happened sixteen years ago, that even then was laughable, and now, as I recount it, seems almost unbelievable. In 2007, the then-minister Nilofer Bakhtiar was harangued (by Lal Masjid’s clerics) for hugging her instructor after completing a parachute jump in France (for charity, no less). The photo was printed in newspapers, and this ‘hug’ took on national importance, even as Bakhtiar said it was a congratulatory pat on the shoulders (which is even more innocuous than a hug, not that it even matters!)

Frankly, if I had just fallen out of the sky I would have hugged anyone, kissed the ground etc, but this instead became a rallying cry for this woman’s death. She resigned, and the story dominated headlines for weeks; so pervasively that is still imprinted on my mind nearly two decades later. Of course, it was patently obvious that there is a double standard, particularly in a culture in which if a man had done this it would have been fine, especially given that ageing politicians’ questionable virility is part of their appeal to the electorate, but that’s neither here nor there, is it?

You may think this might not happen to you - after all, you might not be wearing a dress with innocuous words on it, you’re not a controversial person, maybe you never express any opinions in public, let alone about the number of husbands one should have, and you’re not doing a parachute jump for charity.

But a few years ago in a real estate agent’s office, several men began talking, unprompted by me, about Aurat March, and what I thought of a man’s placard. Someone shoved a phone with a video at me, he demanded that I offer my opinion (which really meant that he wanted me to denounce the man, the march, women, my gender, the whole nine yards.) I had to talk the man down — a skill I only know from years of working as a reporter. Reader, I was there to ask about rental apartments. It was a good reminder to not use that real estate agent, and that we’re all one off-the-cuff remark away from facing down a lynch mob. You should have a Notes app apology, a disguise, and a ‘get out of this country barely alive’ plan at all times. Or perhaps, in lieu of this, a kurta with an apology inscribed on it, and then another apology apologising for the kurta, and so on, until we’re all just apologising, all the time.

Saba Imtiaz is a writer. She is the co-author of the upcoming book Society Girl: A Tale of Sex, Scandal, and Lies in Pakistan (Roli Books) and the author of the novel Karachi, You’re Killing Me!

Saba Imtiaz is a writer and researcher. She is the co-author of the upcoming non-fiction book Society Girl. Her first novel Karachi, Youre Killing Me! was adapted into the film Noor starring Sonakshi Sinha. Saba has contributed to the New York Times Magazine, the Guardian, and Marie Claire. She writes about culture, food, and urban life, and is the co-host and co-producer of the Notes on a Scandal podcast.