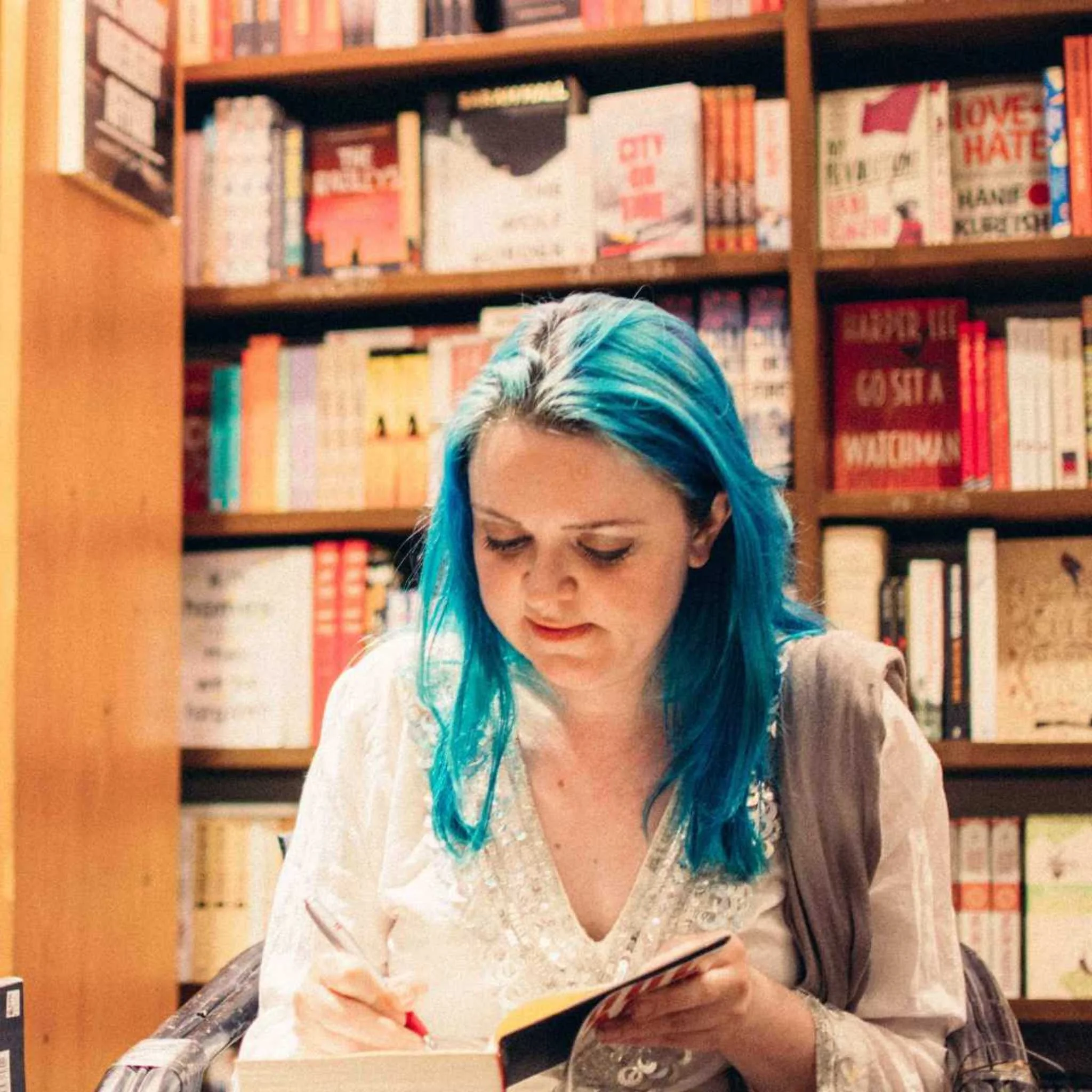

Iwas supposed to interview Alex von Tunzelmann for the Indus Conclave in October last year but she had to pull out at the last minute because of Covid. So earlier this year on the sidelines of the Lahore Literary Festival I met with Alex von Tunzelmann in Lahore. She looked at home in her flowing animal-print shirt and signature bright blue hair. Alex has authored several books on history and ‘Indian Summer’, arguably the most popular of her work in Pakistan, is about the end of colonial rule in British India. Among a sea of books defending the British Raj and arguing for the benefits it gave us as a society, her book stands out as it takes an honest look at the struggles that led up to the independence of the Indian subcontinent, with an admiration for Indian actors that shines through the narrative. Her latest book, ‘Fallen Idols’, written and published during the Covid-19 lockdowns, focuses on the histories told through statues and what we attempt when we pull them down. With a great sense of the ridiculous, the book is a delight to read. During the following interview, which has been edited for clarity, we discussed the writing of history, Alex’s inspirations, digging through the archives and why the British should give back their former colonies’ artifacts.

You have a degree in history from Oxford University. How did you become interested in the subject?

I thought, growing up, that I’d probably study English Literature at university. I’d always had an interest in it but when I was studying for my A Levels, I realized that I was so enjoying the history course. I was connecting with it, looking to the past not just to understand the present but also to develop an understanding of the world. I changed my mind at the last minute and decided to do history. I never regretted it.

Did you specialize in one area during your undergraduate degree?

At Oxford they refuse to let you specialize. They actually have almost a policy where you can’t do two chronological papers next to each other. So you have to split and take modules in various periods in time. What’s called Modern History at Oxford is AD so they have a very different idea of what “modern” is. And then the other is Ancient History. Modern History isn’t what most people would consider modern – we think that is the 20th and 21st century history. But that was very interesting for me because it forced me to think about a lot of periods of history that I wouldn’t have thought about. One of the best papers I did was on the Spanish Conquest of America.

‘Indian Summer’ was your first book (apart from ‘Reel History’). How did you become interested in the subject?

I actually hadn’t done any Indian history at university. After I graduated, I became a researcher, doing background research for busy authors who didn’t have time.

Can you tell me who?

Yes, I am credited in the books. So I worked for a British journalist Jeremy Paxman. The first book I did with him was “Political Animal”, then I did “On royalty”. Through these I was learning because I was reading thousands of books and immersing myself in all this rich history. I became interested in Lord Mountbatten and the extraordinary life he had had. I read an offhand comment in a book (I don’t remember which) about his wife’s relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru and found it extraordinary that two of the main people at the forefront of these historical events may have had a romantic relationship. I decided that I wanted to write a book with this at the center, not in a tabloidy invasive way, but because I think we arrange history a lot around wars and politics, but we don’t think about the human relationships that propel it, we don’t think about love. It was deliberately a somewhat radical take. And it was important for me to respect the Indian and Pakistani positions on what happened. My father was a New Zealander, somebody from the periphery of the Empire who had moved to Britain and he definitely took a very anti-colonial position, which was not pro-British. I definitely failed the Cricket Test! But then I went to a place like Oxford, which is at the very center of the British Establishment, and I found a lot of it quite ridiculous, and that really comes through in the book. Not to underrate the violence and damage caused by the British Empire, but I especially found the pomposity ridiculous. It needed highlighting.

‘Indian Summer’ is at least a decade old now. How did you research for the book, as well as your recent ‘Fallen Idols’?

I went into the archives, in various places. I spent a lot of time in Southampton where the Mountbatten archives are, and of course a lot of the Mountbatten archives you’re not allowed to see. The archivists there are incredible, very helpful but of course there are certain documents restricted by the family, like the letters between Lady Mountbatten and Nehru. That is a decision taken jointly by the Mountbatten and Nehru-Gandhi families. I tried to persuade Sonia Gandhi at the time to let me look at them. I got absolutely nowhere.

As the daughter-in-law, I’m sure Sonia Gandhi’s position was especially difficult, not having the sort of authority to say “yes, go ahead”. Maybe if it was Indira Gandhi, you could have gotten somewhere.

Yes. I think so. It’s a very big decision and I understand her position would be difficult. Of course I had to try but I didn’t expect to get anywhere. There was a lot of material I was able to use and they were incredibly helpful. I went to Delhi and went through the archives there, which was much easier to do back then. It’s harder for researchers to get visas now.

Even for you?

Oh yes!

Because for Pakistanis wanting to write our own history, I only know of Ayesha Jalal who’s been able to research archives in both India and Pakistan.

It is a real problem. And we need South Asians to write history. This just makes it very obstructive. For Brits, previously you could go on a visit visa [to India] but now they dont let you. You have to get a proper visa and that is very difficult. When I was writing ‘Indian Summer’, I contacted the archives and asked if I needed a special visa for research and they laughed at me. I researched in the National Archives in Delhi and the Teen Murti House, which is the Nehru Memorial Museum. There have been political changes so it’s a different attitude now.

When you were at Oxford, were there many South Asians teaching history?

There are much more now than there were then. There are many more people doing that, like Yasmin Khan and Priyamvada Gopal at Cambridge. And there is a lot more room for greater diversity.

There is some conversation now about colonial artifacts in foreign museums. What is your opinion on that?

‘Fallen Idols situates me firmly within that debate. There has been a lot of talk recently about the Elgin Marbles, now called the Parthenon Marbles, and we’re moving much closer now to repatriating them. It would be the right thing to do, there’s no question.

Do you think that Greece being a white country has played into this decision? As opposed to returning artifacts to other formerly colonized countries, especially countries like Pakistan and India who can’t decide what belongs to whom?

Maybe it does, yes. Look at the Koh-i-Noor. Fascinatingly, the King and Queen have said they don’t want to use it for the Coronation, which I’m sure is because of the controversy around it. And this is just my hunch, that King Charles, who has quite an international perspective, would probably love to give that back. The question is: who do you give it back to? It would be such a statement to give it back, and they don’t want it. I mean, it’s basically a paperweight! And they’re not even using it. I’ll refer to Anita Anand and William Dalrymple’s brilliant book on the Koh-i-Noor when I say: “Who do you give it to?” Because India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan all have a claim, so what happens? How do you decide between these competing claims?

And coming to your question about Greece, about whether there is a racial element. I think it works in a couple of complicated ways. Firstly, there is definitely some racism in this whole discussion. But you also hear racist remarks in Britain about the Greeks and that these people can’t look after the Parthenon Marbles. Although the Greeks are white, I think there is racism against them in Britain, as if they’re not the ‘right’ kind of European. On the other hand, the British see themselves as Ancient Greeks, whore considered the pinnacle of European civilization. There is this sense in the British elite that we are learned and cultured like them, so of course these belong to us, which is of course ridiculous. So the racial question is very complicated.

Like Edward Said says, about this identification with the Greeks.

Yes. Edward Said is the perfect reference here. But politically, I think we’re moving much closer to repatriation in recent months. And museums are getting much better at understanding the criticism and pushback. Some museums are doing wonderful work, such as the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford under Dan Hicks, who wrote “The British Museums”. He’s doing fascinating work. And I was just in Vienna, Austria and they have a colonial museum, which in the past was very regressive and they’ve completely changed that. They’ve refigured it around the collectors, so they’ve told the story of colonial looting and what happened. It has a whole room discussing whether it is even appropriate for them to have all this, how they should deal with it, what they should do. They’re encouraging discussion and looking much more at the motives of the collectors very critically. They talk about how destructive they were.

In art history, there is a lot of scholarship around the art stolen from the Jewish people by the Nazis for the Linz Museum that Hitler wanted to build. And a lot of legal work has also been done on restitution. It would be fascinating if this sort of work would be done for formerly colonized countries.

It would and I do think there’s been a start and conversation has started. Not everything should be repatriated because some things were travel souvenirs and not necessarily taken by force. I would like to see cultural exchange and would like to see museums communicate with other museums in places like South Asia and ask, ‘what can we give you?’ There are some things that should very obviously be repatriated, but exhibitions of others would also be great. And one of the things that should be returned is human remains taken from places like Australia and New Zealand. And these places have very strong feelings about the remains of their ancestors. It’s completely inappropriate that they’re being displayed in any way.

Are you working on another book?

I’m just about to but I’m afraid I’m not quite ready to talk about it yet.

Madeeha Maqbool is a civil servant and a writer. Her work has appeared in The News on Sunday, The Friday Times, and Libas, amongst others. She is obsessed with non-fiction and runs a popular Instagram account called @maddyslibrary where she talks about books, colonization, and women's rights.