In 1965, the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Raza Pahlavi, visited Pakistan. For a state dinner in the Shah’s honor, West Pakistan governor Amir Mohammad Khan wanted to put on a show. He asked renowned actress Cynthia Alexander Fernandes, better known by her screen name Neelo, for a dance performance. Neelo refused, allegedly because she did not want to perform for a gathering of autocrats (Mohammad Khan sahab was also Nawab of Kalabagh, a feudal with generations of wealth; the Shah was, well, the Shah). Predictably, the governor was furious. He had the police forcibly bring Neelo to the event. Humiliated, she overdosed on sleeping pills. Upon stepping onto the dance floor, she fainted.

Habib Jalib, the progressive Marxist poet, wrote a famous poem about the incident. Addressing Neelo, he mockingly wrote:

Tu ke nawaqif-i-adab-i-shehanshahi hai abhi

Raqs zanjeer pehen kar bhi kya jata hai

(You are unfamiliar with the rules of the king

Didn’t you know one can also dance while in chains?)

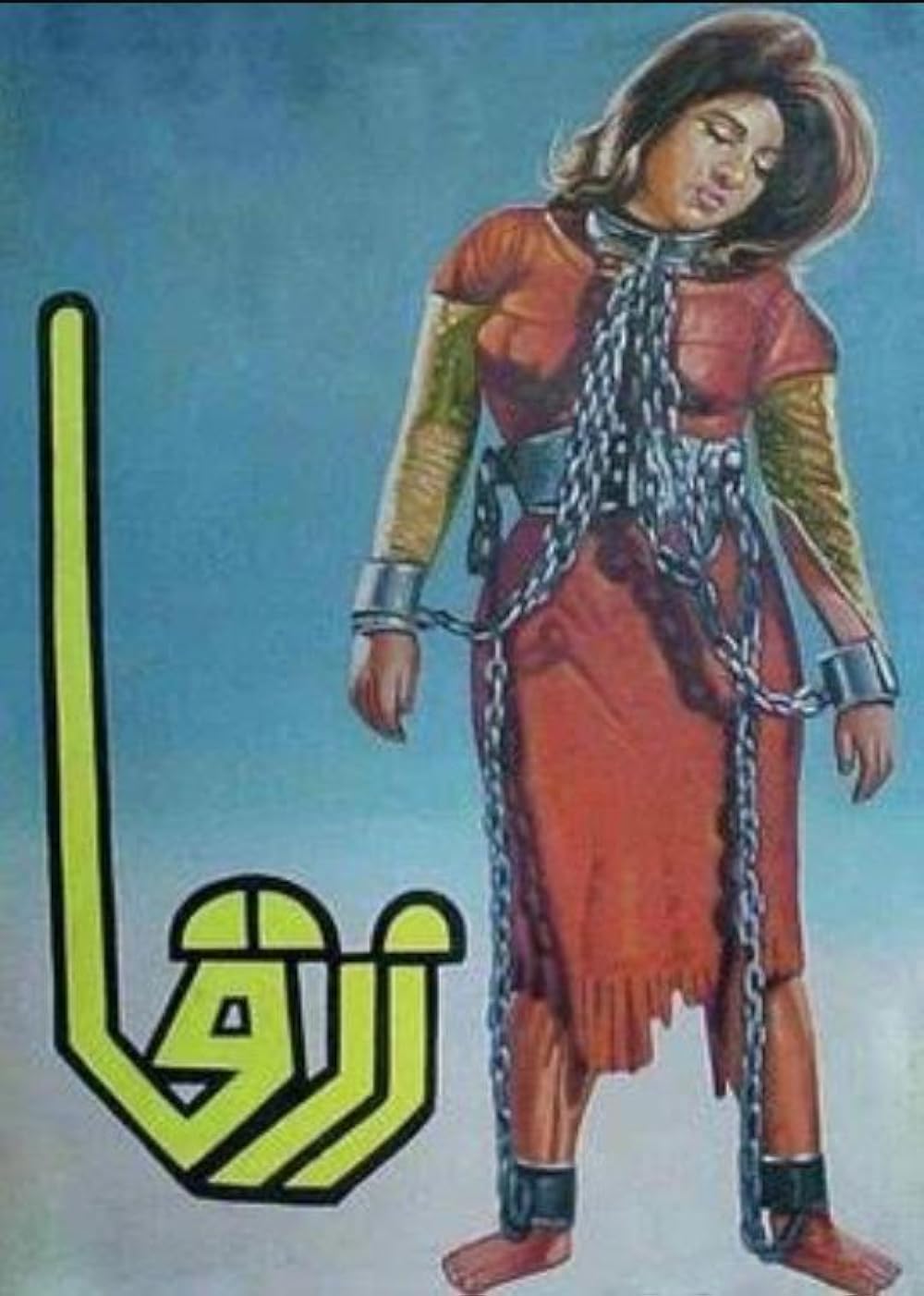

Like with so much of our national history, this story lives on as oral lore. I heard about it from my father, although one can also find several retellings on the internet. In the past few weeks, I’ve gone back again and again to this story, and to Jalib’s poem. Partly, this is because the poem was later turned into a song for the hit film, Zarqa, which tells the story of a Palestinian dancer who becomes a freedom fighter. In what is perhaps the film’s most memorable scene, the eponymous Zarqa, played by Neelo, dances in chains in front of an Israeli general. Mehdi Hassan’s voice shivers in the background.

Raqs zanjeer pehen kar bhi kya jata hai

I am also thinking of this poem because I live in the US, where the current environment is stifling and hostile. Students have been shot at for wearing keffiyehs, artists speaking against Israeli occupation have been penalized, and several institutions have canceled events discussing the ongoing bombardment of Gaza. Amid all this, seeing artists, writers, and thinkers continue to pretend at business as usual and prolong the charade that artistic freedoms in the US are absolute and unchallenged has been nothing short of horrifying. In Pakistan, of course, we more forthlightly gave up on the charade a long time ago. What happens in Turbat and Torkham was never our business to begin with. Daily, I wonder if we are all living Jalib’s prophecy, dancing while in chains. In another famous poem, he wrote:

Zulmat ko zia, sarsar ko saba, bande ko khuda kya likhna

(How can I call darkness light, or the desert wind a morning breeze, or a mere mortal by the name of God?)

Like most gestures at fatigue, mine is ill-earned. A search through the chequered, bullet-ridden, bomb-ravaged past century of ours shows that art and music have constantly played their part in resistance. Mahmoud Darwish, the famed Palestinian poet, devastatingly said towards the end of his life, "I thought poetry could change everything, could change history and could humanise...but now I think that poetry changes only the poet." But that did not stop him from writing verses that, in their lyrical aspirations and indelible imagery, shed light on the cruelty of the occupation. Darwish was born in 1941 in Al-Birweh, a village in historical Palestine. In 1948, he and his family were among the 750,000 Palestinians forced out of their ancestral homes, in the mass displacement that is known today as the Nakba. Darwish was designated a present absentee, a dystopian term in Israeli bureaucratic vocabulary for Palestinians who were displaced from their houses but remained within the occupied territories. One of his most famous volumes of poetry is titled “In the Presence of Absence.”

Today, it has been 15 years since his death, and 75 years since his family was driven out of the Galilee, but any time Palestine faces assault, many of us go back to Darwish’s words for solace and strength. He is considered the national poet of Palestine, even though the label grated him throughout his life. “It is a burden,” he said once. But who gets to choose their burden in this life? Certainly not the Palestinians.

So is that what art does best, then—provide comfort and strength to those who succeed us on this earth? Perhaps being an artist means believing, even if reluctantly, in immortality. One’s art must outlive the body and feed the revolutions of tomorrow. I’m not convinced that it can feed the revolutions of today. Jalib’s words didn’t take down Zia; a C-130 flying over Bahawalpur did. Darwish recited in football stadiums filled with thousands of Arabs. Iqbal Bano’s voice and Faiz’s words boomed at Gaddafi Stadium. The Shaheed Minar went up in Dhaka to honour the martyrs of the Bengali Language Movement. Susan Sontag helped the Bosnians stage Samuel Beckett’s famous play, Waiting for Godot, in war-struck Sarajevo. Political murals donned wall after wall in the Northern Ireland of the nineties. All for what? Susan didn’t stop Srebrenica. At the end, the things that made a difference were either more lethal or more prosaic. A plane crashed. Important men signed papers in Dayton, Ohio. There was a resistance army by the name of Mukti Bahini. The Palestinians still wait for Godot.

Often, art resists best at a slant. A necessary lesson in humility for any artist is to witness material resistance, whether it is that of the freedom fighter asserting their dignity or the surgeon keeping children alive or the journalist fighting to get the truth of war out. It is necessary for us to see that even as we daily face the task of housing a small fraction of human experience—cruelty, resilience, bravery, horror—within the insufficiencies of language, the task of daily survival remains in other hands. What art does instead is give us the audacity to survive, by showing us why this life, in all its injustices and imprisonments, is worth fighting for. Faiz wrote:

Mai-khana salamat hai to hum surkhi-mai se

Taz.in-e-dar-o-bam-e-haram karte rahenge

(As long as the tavern lives on, we will continue to use

The dye of wine to adorn the sacred mosque)

Art is the tavern that lives on.

There is also art that does not call itself that. There are moments of poetry that do not announce themselves as heroic. How a besieged mother symmetrically portions out bread among her children. How a father sculpts his body to protect his daughter under bombardment. How people line up empty containers to fill with rainwater. How a stone makes a perfect arc as it approaches the tank.

I return again to Darwish, who said, in an interview, “I very seriously advocate [the Palestinian people’s] right to be frivolous. I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous. The sad truth is that in order to reach that stage of being frivolous we would have to achieve victory over the impediments that stand in the way of our enjoying such a right.”

In the light of grave injustice, so much of the art that we make and enjoy can seem unserious and frivolous. How to describe the precise grey of the beloved’s eyes, or paint the sea, or sing about the circus, when confronted with the horrors of war? But even Darwish, imprisoned, exiled, censured—Darwish the present absentee—knew that what we all want, what we all deserve, is a life that allows for frivolity. The oppressed fight not only for the survival of their bodies, but also the continuation of their levity and laughter, of the laughter of their children, and of their art.

On December 6, 2023, Israeli forces targeted and killed renowned Palestinian poet and intellectual Refaat Alareer. The final verses of his last poem—”if i must die / let it bring hope / let it be a tale”—are haunting and prophetic. Within a week, they have been scrawled on train station walls all over Manhattan, made into placards for protests, and translated into most major languages. According to Euro-Med Monitor, Dr Alareer’s murder happened after weeks of “death threats…received online and by phone from Israeli accounts.” For years, he had been educating writers across Gaza, arming them with the English language so that they could tell Palestine’s story to the world. In a lecture given in 2019, he rejected the defeatist attitude artists sometimes assume. Speaking of the great Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan, he says:

“Of course, we always fall into this trap of saying, “She [Fadwa Tuqan] was arrested for just writing poetry!” We do this a lot, even us believers in literature … [we say], “Why would Israel arrest somebody or put someone under house arrest, she only wrote a poem?” So, we contradict ourselves sometimes; we believe in the power of literature changing lives as a means of resistance, as a means of fighting back, and then at the end of the day, we say, “She just wrote a poem!” We shouldn’t be saying that…Don’t forget that Palestine was first and foremost occupied in Zionist literature and Zionist poetry.”

The oppressor has art too—art that is weaponized to dull the senses, char judgement, provide catharsis where resistance is required. We must remember that empires have always needed stenographers to document their inevitability, just as resistance has always needed the artist to beckon its future.

Dur e Aziz Amna is the author of the novel American Fever, winner of the 2023 APALA Award and the SABA Award. She has also been published in the New York Times, Financial Times, Aljazeera, and elsewhere.