First, a disclaimer.

My earliest memories are of a rented lower-portion house in Lahore, which abutted a school. Though we lived on the ground floor, the tenancy allowed us access to the roof, from where we could look down upon the school ground. I must have been very young, because my mother is incredulous when I insist that I remember, but I remember being taken up there by her in the mornings and hearing the schoolchildren recite the national anthem. Once, held by her, I was allowed a glimpse over the roof wall. I remember a grid of children in dark colours – your navies and maroons, aspiring to featurelessness – facing away from me and towards a dimension governed by time. I, being no more than three, lived firmly outside of this dimension.

In this same house, we planted an orange tree. My mother made an exciting event of it. In the corner of the tiny yard, she encouraged me to pat the earth where the seeds had gone. Five years from now, she said, there might be fruit.

Will we eat it? I asked.

Maybe. If we are still living here then. If we’re not, the next family will have an orange tree full of fruit in their yard.

Before I was inducted into the themes and imageries of social studies textbooks in primary school, life made obvious for me the threads that run between home and country, individual and collective, present and future, sowing and reaping.

At first, it dismayed me to think of strange children eating from my orange tree.

Later, it dismayed me to think of my great-grandfather’s pre-Partition prosperity in India confounded into a modest life in Pakistan, far away from the border, that tensile cord. If he hadn’t been forced to flee, we would still be landed. If he hadn’t been forced to flee, I would be eating from an orchard of orange trees.

Later still, it dismayed me to think that accounts of my great-grandfather’s pre-Partition prosperity may have been exaggerated. Some people I met rolled their eyes and laughed and said, oh yeah, everyone’s great-grandparents were nawabs back in India. Sometimes, these people belonged to families who lived on vast properties in Lahore strewn with reminders of hurried evacuations by former Hindu or Sikh inhabitants. I rolled my eyes back at them. I had heard those stories, too.

And later, when I was far too old to be learning of it for the first time, I learned of the sheer scale of violence my country perpetrated against itself, or what was once a part of it. When I asked my elders about the 1971 genocide of Bangladeshis, they said oh, you mean the war of ’71? Our armed forces should have returned victorious. It was a complete disaster, they said. It was, I thought, aghast, but not for the reasons you think. Some replies were facetious, to do with getting holidays from school because the air would be hot with sirens.

Last year, I moved away from Lahore. My partner and I left Pakistan, like scores of others our age, or a little older, or a little younger, homogenised mainly by an urgency to get out. We crossed several borders, and crossed them in pre-approved ways. I cried all the way to Istanbul. On reaching Helsinki, I felt bereft. But there, right where I felt scooped clean out, sat privilege.

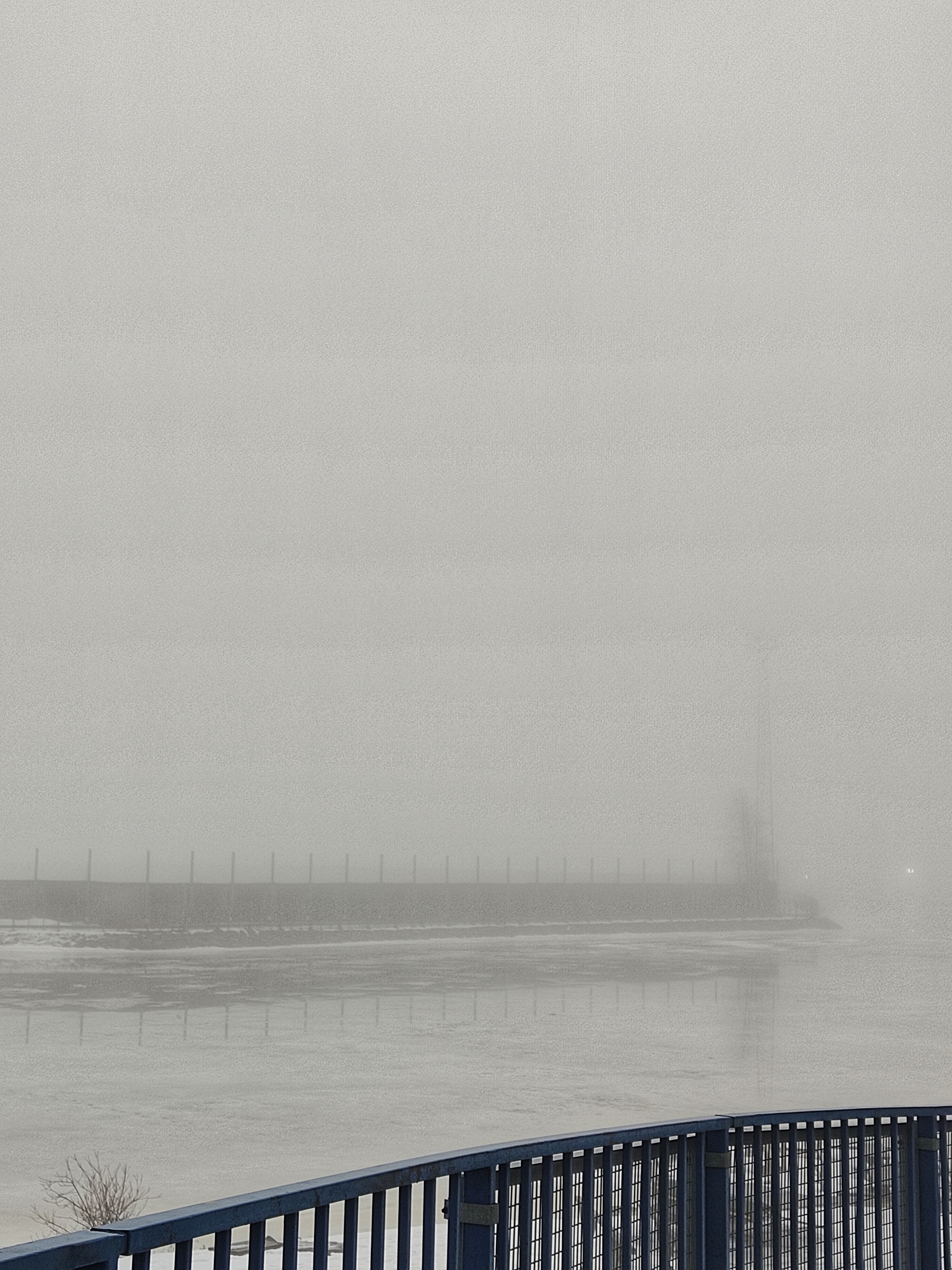

In the morning, I looked out the window of our apartment. There was a jungle gym underneath. Then some grounds, sloping down and away. In the distance, on the wall of a building that was a school, a clock, big and white.

I resisted this. When I was initially asked, I declined to write about being a Palestine supporter newly arrived in Europe. What does my experience of the genocide in Gaza – mediated in every sense of the word – have anything to do with anything? I’m not Palestinian; I have none of the Palestinian courage or faith. I have only looked on, like countless others, in leaping anguish at instance after instance of this courage being tested. And if I loved my land even a fraction as fiercely as the Palestinians do theirs, I would not be sitting in Europe, wringing my hands.

Europe.

I have been here eight months. Which is to say that there are days when I feel like I am camouflaged, like I have mastered the facial and verbal reticence that is the norm here – certainly, the norm in Finland – and that I have wound down, wound down to a deep and silent trickle, the boisterous workings of my South Asian blood. In 2021, high in the north of Pakistan, I had felt the heat of my failings in the vast, cool presence of a glacier. And somewhere, running beneath or through the enormous icy ridges, had been a trickle of water. And somewhere, where the trickle receded, a small black bird sang to and in spite of the ice.

Your lessons can be impossibly disparate but time will find a way to connect them.

Now, five out of eight months of ice have taught me delay. How to practise it or, at the very least, aspire to it. But there are days, still days, when the people, the landscapes, the streets, signs, sounds, feel alternately alive, in thrall to a different time.

In the wake of October 7, 2023, this began to feel truer. Life carried on in the wide, empty streets of Helsinki, people moved briskly about, curt and invariably contained. Meanwhile, a torrent of images from Gaza. Nothing as it should be. Every conceivable vessel – homes, bodies, wombs, archives – blown apart by Israel, with American bombs. A spillage to drown the world thrice over. But life carried on. Here. As well as in Pakistan. On call with my parents, I would try to loop them into an exchange of horror and incredulity. How can this be allowed to happen? Have you seen what they did today? And my father, after commiserating, would remind me to be careful. My partner and I had come here to study; we should grieve in our hearts and perform respectability – the good foreigner, functional vessel, keeps contents inside.

In November, December, and January, I attended protests. While the numbers here were sparser compared to other Nordic capitals like Copenhagen and Oslo, it felt productive, somehow, to chant Free Palestine! in Finnish. I admired the spirit and resolve of Sumud, the Finnish-Palestine network organising these protests in increasingly hostile, sub-zero temperatures. Weekend after weekend, even as attendees dwindled, the young organisers would lead us on a march from the railway station to the parliament house for speeches, songs, protestations. Finland, which does not recognise Palestinian statehood, struck a 316-million-euro deal with Israel in 2023 to acquire David’s Sling, a high-altitude missile defence system. Israel, peddler in ironies and bloodshed (in characteristic fashion, deigning itself the underdog when it is and has always been the implacable, armoured brute), prides itself on arming much of the world while claiming victimhood, sainthood, brotherhood. The camp that still wishes to ascribe nuance to what is unequivocally a black-and-white situation ought to consider: a country who thrives on military industry is certainly not interested in a world without war.

Divest from arms deals with Israel! Protestors would shout, facing the steps of the parliament house. Stop bombing children! Stop bombing children! A Finnish woman next to me at one of the marches screamed herself hoarse. Her rage soothed me, because three months into the genocide and the lies, it became imperative to seek in the mild, impassive faces around me some assurance that the horror was not singularly felt. That the occasional keffiyehs on strangers taking the same bus or the tiny Palestine pin on the odd backpack were emblems of a shared fury.

In my graduate programme, we talk a lot about sharing. We talk of cultures of care and collective action and a return to the earth. This is symptomatic of much of Western art education at this point. But no matter how well-intentioned, it is hard to see these leanings as completely divorced from centuries of imperialism and industrial capitalism. When, little by little, family, kinship, and community have all been subsumed by the useful individual, and when useful individualism has directed the focus of desire only inward, inward, inward, something is bound to feel off eventually.

So, we talk of materiality (not to be confused with materialism, it is reiterated) – what it means, what artists can make of it, how it can awaken a greater sense of communion with the earth and one’s environment. We read and talk at length about stones, soil, compost. We talk about the memory of stone and the memory of flesh, of impressing upon and embedding in. We look at artworks that attempt to capture the inchoate grandeur of storms, the strange rhythms of wetland life, the impinging and receding of floods. A guest lecturer talks about the expansiveness and specificity of touch. Touch as container. Touch as cord. Another reads from Ursula Le Guin’s Being Taken for Granite (“I am still here and still mud, but all full of footprints and deep, deep holes and tracks and traces and changes. I have been changed. You change me –”). Another talks about indigenous wisdom and we read from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (“…an invitation to settler society to become indigenous to place feels like a free ticket to a housebreaking party”).

And everyone, everyone, skirts around Palestine.

We talk of how there are different kinds of time – deep time and, one assumes, shallow time. How time for the West is linear and for many indigenous societies, cyclical, non-linear. You may plant an orange tree knowing its fruit will go to someone else. I think of a harrowing essay by Suja Sawafta about the sea of Jaffa, which keeps bringing back to shore the evidence of Israel’s destruction of Palestinian homes and lives; what debris is dumped in the sea, the sea leaves strewn on the shore, again and again. The sea remembers, the land carries traces, what you do has repercussions. But those who are proficient in governance, in modern time-keeping, hem themselves in, hem in others, in a tangle of stopgaps. They make their time the only time, and their time dictates instantaneity, acquisition, get, get, get with it, or be left behind.

I think of all this as everyone, everyone, skirts around Palestine.

I think of this as I take the metro home and on my phone see the ambulance that went to rescue little Hind shelled to inconsequence by Israel, see Aaron Bushnell go up in flames because he lost his footing on expediency and found his moral centre.

I think of all this at home as I hear the children during recess in the ground outside – a confusion of shrieks, whoops, and the urgent scorekeeping and negotiating of the young. The children of Gaza had held a press conference in November, begging the world to protect them. In English, a language they felt would be understood everywhere, they had said, “We face extermination, killing, bombs falling over our heads. All this in front of the world.”

“The [Israeli] occupation is starving us,” they had said.

“We invite you to protect us.”

I think of it as I hear the schoolchildren queueing up to go back to their lessons, recess over. I see them getting initiated into time.

On certain days, the clock in the distance catches the glare from the snow and erupts in an angry, jubilant obfuscation of time.

Dua Abbas Rizvi is a visual artist and writer from Lahore, Pakistan. She has written on art and culture for The Herald, Dawn, The Friday Times, ArtNow, and The Aleph Review and contributed essays on South Asian and Islamic art to Encounters: The Art of Interfaith Dialogue (Brepols), the Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception (De Gruyter), Image Journal (for which she also serves as an editorial advisor), and Selvedge Magazine. In 2022, she was awarded a South Asia Speaks Fellowship to develop her first book of visual nonfiction. She is currently studying towards a master’s degree at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki.