Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1220 to 1250, was a polymath who was fluent in five languages, including Arabic and Greek. He had translations made of works by Aristotle, Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina, and then had copies of these sent to newly established universities in Paris and Bologna with cover letters explaining his need to “inhal[e] tirelessly [knowledge’s] sweet and balsamic perfumes.” Raised in multicultural Sicily, Frederick was surrounded by Arab intellectuals and craftsmen who produced their works now for their new Christian rulers. The Emperor, writes William Dalrymple in his new book, was “a model of inquisitive tolerance and multiculturalism in an age of religious absolutism.”

“The Golden Road” traces the evolutions and dissemination of ideas from ancient India to the rest of the world, ideas that reached Frederick II through Arab intellectuals who had adopted Indian mathematical and astronomical innovations, the idea of madrassahs from the Buddhist viharas, as well as Greek teachings, to create a formidable intellectual structure by the middle ages, ranging from Haroun al Rashid’s Bayt al Hikmah to universities such as Al Azhar. These ideas, discussed in the latter half of the book, present the strongest arguments and form the most comprehensive part of the entire narrative. Dalrymple narrates a fascinating history of how ideas from ancient India traveled to the Arab world, helped along by a multilingual family called Barmakid who served as royal viziers in the Ummayad, and then the Abbasid courts. They spoke fluent Hindi, and had access to writings on Indian mathematics and astronomy because, before converting to Islam, they had been rectors of one of the biggest centers of Buddhist learning, Naw Bahar, in Balkh in what is now Afghanistan. Encouraged and disseminated by intellectually voracious rulers, these ideas found an audience in the Arab courts, from where they spread via the Spanish Muslim kingdoms to the rest of Europe.

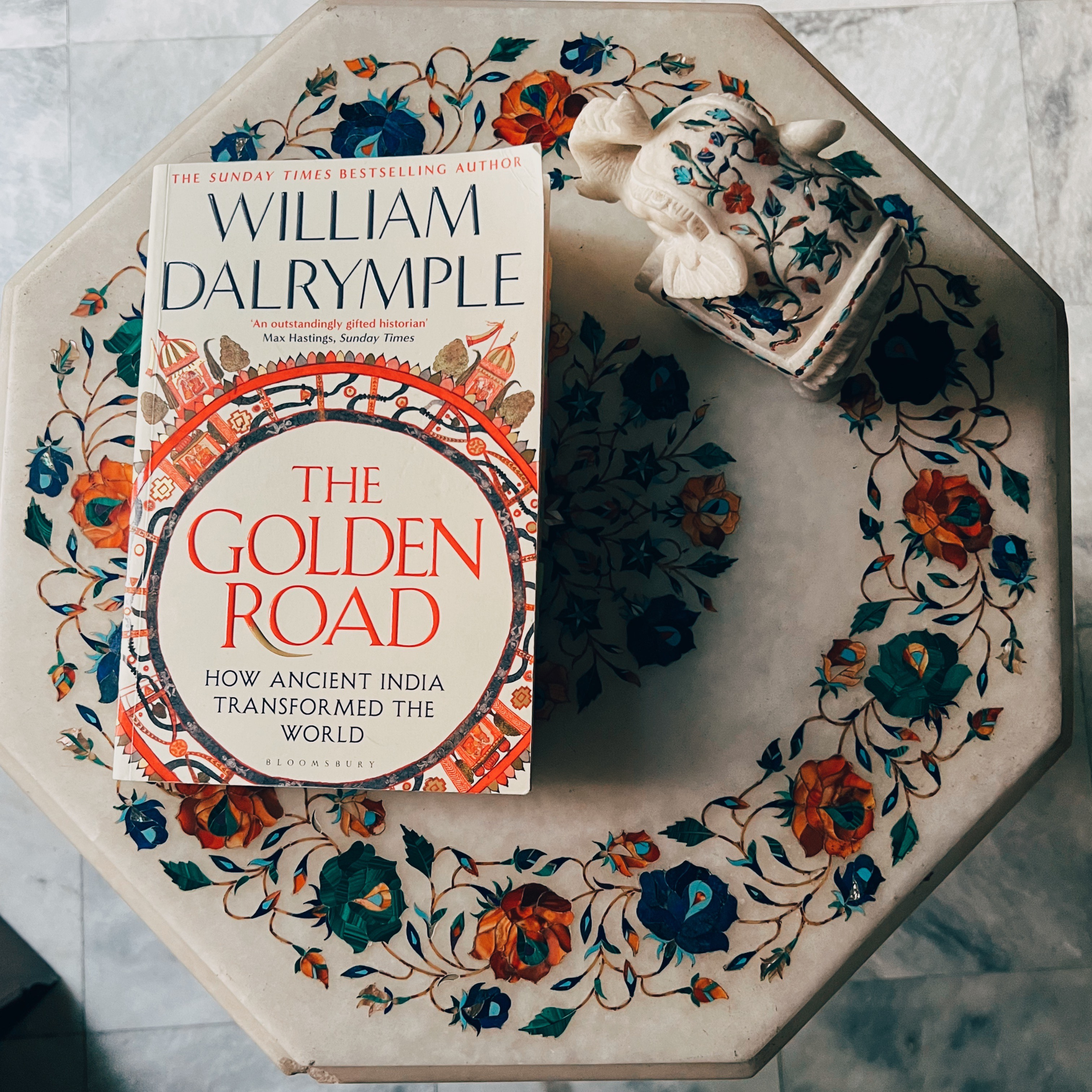

William Dalrymple introduces his latest book, ‘The Golden Road: How ancient India transformed the world’ as a reminder that India’s position as “a crucial economic fulcrum” and “civilisational engine” in ancient and medieval times was “fully on a par with and equal to China”. He presents the idea of a “golden road” as a counterweight to the Chinese Silk Roads that have been written about ad nauseam, and are at the heart of China’s “Belt and Road” initiative. This is a premise that is sure to be popular in the saffron-washing, anti-Chinese political climate in India fostered over the past decade by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party government. The road that is at the heart of Dalrymple’s book is more a rough geographical area corresponding to monsoon rainfall patterns than an actual road, and charts the spread of elements of Indian thought and culture across a large swathe of Asia and Europe. Moreover, what exactly constitutes “ancient India” is not particularly clear. Dalrymple has been criticized in the past by the Hindu right-wing for his focus on the Mughals and the British. This book may be seen as a way to pacify some of these critics by writing an ode to the ancient Indian civilizations. However, his focus is more on Buddhism and the later mathematical and astronomical developments that contributed to the flowering of Muslim dynasties. Although described in some detail, the development of the Hindu religion interests him more in terms of the architectural proofs of its influence across Southeast Asia, with special attention paid to Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

Dalrymple traces the development of Buddhist thought and its expansion to China and Southeast Asia in riveting detail. The book is filled with evocative descriptions of forests, mountains, monasteries, stupas, sculptures, libraries and temples, and especially people. The last is where the author is most comfortable. His previous books have largely focused on recounting stories about individuals, whether it was the dramatis personae of the Mughal Empire or the British Raj. Here too, he narrates personal histories of the people involved in encouraging Buddhism’s import to and spread in China, histories that crowd out the discussion of intellectual and religious influences. An example of this is the space given to narrating the rise to power of Empress Wu Zetian, who patronized Buddhism. However, the details of the actual “civilisational conversation” are mentioned as just that in a single sentence towards the end, and not elaborated on. Dalrymple pays attention to the archaeological evidence of trade with the Roman Empire and with Egypt, such as the gold Roman coins found at Indian sites, the Indian peppercorns filling the nostrils of Egyptian pharaohs’ mummies, and Pliny the Elder’s complaints of the Empire losing money to India just so rich women could wear see-through clothes. This all makes for entertainingly informative reading.

It is only at the end of the book that the author mentions the contemporary religio-political climate in which he has written this book. He mentions the “Nehruvian” policy of developing history curricula that played down historical differences between Hindus and Muslims to counter the sectarian violence that broke out during the Partition of 1947 and to build a secular nation. He alludes to the paradigm shift in contemporary India in one line, stating that “the reverse is true” now under the BJP. He then proceeds to reiterate the lessons taught by the aforementioned “left-leaning” elite historians who posited that the Turkish invaders assimilated into India, and highlighting the tolerant policies and cultural exchanges of rulers like the Mughal Emperor Akbar and Dara Shikoh. This unwillingness now to dwell on the BJP’s record of revising history to fit its increasingly rightwing and violent creed is a significant departure from his own essay penned in 2005 for The New York Review of Books which traced the historical evolution of Indian thought and of its twentieth century record of shifting points of focus in history-writing. It is that Dalrymple who may have been better suited to write The Golden Road. Perhaps in that case, such fundamental shifts would be more fully explored; the book would have certainly been richer for it.

Madeeha Maqbool is a civil servant and a writer. Her work has appeared in The News on Sunday, The Friday Times and Libas, amongst others. She is obsessed with non-fiction and runs a popular instagram account called @maddyslibrary where she talks about books, colonisation and women's rights.