Lahore is currently blanketed in a haze of toxic yellow smog so thick it is visible from space. Air pollution in Pakistan has been multiple times higher than WHO guidelines since at least 1998, but the last 10 years have marked a tipping point, where the intensity of the pollution during winter months has led to increased hospitalizations, disruptions of flights, and closures of schools, offices, and parks.

This past week alone, Lahore’s air quality index (AQI), a measure of pollutants in the air, exceeded 1000 multiple times. A value above 150 is considered “unhealthy”, and 300, where AQI measuring bands stop, is considered “hazardous.” The Air Quality Life Index estimates that smog shaves nearly 4 years off the average Pakistani’s life expectancy. The 14 million residents of Lahore lose more than 8 years of life on average due to smog.

What is the government doing to tackle these catastrophic levels of pollution in the air? How effective are their initiatives likely to be? What is the right way forward to tackle this unmitigated health emergency? I spoke to Dawar Butt, co-director of the Pakistan Air Quality Initiative and member of the Pakistan Air Quality Experts (PAQx) group to understand the underlying causes and potential solutions to air pollution in Pakistan.

Mariam:

Unlike previous years, it does appear that the Punjab government is taking the smog issue more seriously this year. Do you agree?

Dawar:

There is an understanding now within the Government of Punjab that without doing something about smog, this problem isn't going to go away. In the past, they operated on the hypothesis that the smog will go away once winter rains come. This year, there was a little bit more urgency and proactivity. One of the reasons for this change is that Pakistan is trying to place itself globally as a victim of climate change, and the monetary assistance the federal and provincial governments get is contingent upon what they are able to deliver.

As a result, in May of this year, the Government of Punjab announced the Smog Mitigation Plan of Punjab to prepare for the smog season. However, the plan is focused primarily on Lahore, not Punjab as a whole.

Mariam:

What does the plan include?

Dawar:

They outline some actions they will take: fines on motorists, requiring farmers to stop crop burning, shifting transportation to electric vehicles etc., but it is not comprehensive, or fully fleshed out.

Mariam:

Is there a plan on how the shift to electric vehicles, for example, will happen?

Dawar:

No, there's no systematic plan. They say that the Punjab Government will distribute electric vehicles, but they don’t give details. They have announced that they will provide happy seeders [which eliminate the need to burn crop residue to clear fields] to district administrations, and that these will be available for rent to farmers. This is a somewhat similar model to what India has done, but India additionally provides a wider support price for the crop waste. So farmers are actually incentivized to collect the waste rather than disposing of it by burning it. The Government of Punjab has not done this. Their plan is basically a bunch of things that they want to do, but this approach will not make an improvement, not in the short term, not in the long term.

Mariam:

The AQI levels in Punjab right now would agree with you. Beginning in the first days of November, Lahore saw AQI levels reach higher than 1000. What have they gotten wrong in their approach? Do you think they believed that the smog wouldn’t be so bad this year and that they won’t need mitigation measures like this?

Dawar:

I think they did, partly, because the previous years (2022 and 2023) were slightly subdued in terms of smog. There had been a spike in petroleum prices that created an energy crisis. Fuel consumption declined and industries were shut, so the smog didn't get as bad in those years. Prior to that, during the COVID years, again, we had a relatively easier year in terms of smog.

Government administrators also do not have robust data available to them, so they form perceptions more or less based on how they feel about it.

Individuals in the Punjab Civil Secretariat, the CM office and senior ministers offices, utilize open source data from privately deployed IQAir monitors. However, the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) - whose job it is to monitor the AQI - says the readings from these monitors are wrong. When you ask them if they have comparable data available, they don’t have it, or they do not provide it, at least.

Mariam:

So let’s start with what is causing the air pollution that gets trapped by the temperature inversion at this time of the year. What are the largest contributors to it?

Dawar:

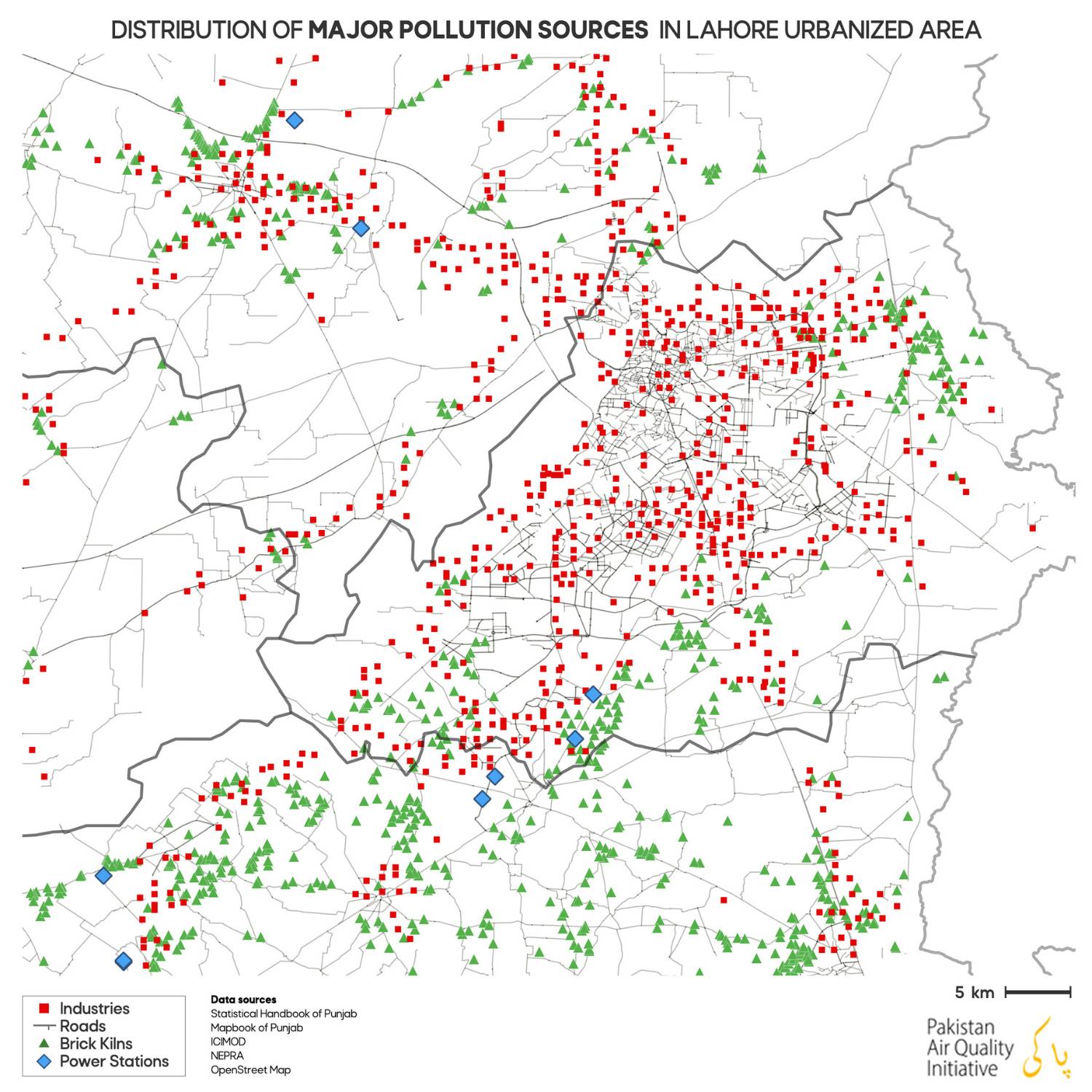

In Punjab, the largest contributors are transport, followed by industry.

Mariam:

Can you speak a bit about how Lahore is taking over all of the conversation about smog, when the air quality is horrific across the entire province of Punjab?

Dawar:

The number one reason is that most of the monitors are in Lahore. There are currently around 20 active monitors in Lahore and that gives you a pretty good picture of the overall city. The media picks up on this and puts it in the headlines, that Lahore is the first or second most polluted city in the world. The government primarily responds to the media critique. If we had more monitors in Faisalabad, Sialkot or Multan, these cities would start popping up in the top 10 most polluted cities as well. We saw this with Peshawar. So right now, I think a lot of the government’s response, the panicking, is trying to assuage the media. But the media also now knows that it's bad all over. If you travel on the motorway from Lahore to Islamabad, it’s the same situation along the entire way.

Mariam:

Several studies have shown that the transport sector is the largest contributor to air pollution, a fact that the Punjab Smog Mitigation Plan affirms. Let’s start there. First, there has been a lot of talk about the significance of the poor quality of fuel that we are using in Punjab. The quality of the fuel Pakistan produces locally is very poor and causes a lot of pollution, and clean fuel (Euro 4 or 5 standard) is all imported. But isn’t that a federal policy issue, which cannot be tackled in Punjab? What are your thoughts on a) how important the fuel quality is in the discussion about tackling the pollution, and b) what the Punjab government can do about it?

Dawar:

You're right that the Punjab government can't control it alone, but they can approach the Federal Government and ask that fuel supplied in Lahore division, for example, should be Euro 4. We have Euro 4 fuel available in Pakistan; it just happens to be restricted to Sindh, particularly because Euro 4 or Euro 5 fuel is imported and it's easier for oil marketing companies to supply it to the closest buy-point, rather than transporting it up-country. What that means is that you will need to have tankers of cleaner fuel that need to come into Lahore for these three months, which is, of course, going to increase the fuel cost itself. This was done in India, where Euro 6 fuel was made available, first for Delhi, and then for the rest of the country.

Mariam:

How much of a price difference will it make to the consumer were we to implement this change?

Dawar:

It won't be more than four or five rupees per liter. It’s possible that the Punjab government can take on the subsidy burden.

Mariam:

What is the breakdown of our fuel mix?

Dawar:

70% of our petrol is imported and 30% is produced locally. For diesel, around 35% is imported and 65% is refined locally [Source: Trade Development Authority of Pakistan, 2021]. Right now, we have more of an issue with diesel. Diesel lands in Karachi, and because Karachi is one of the largest consumption centers in Pakistan, most of it is just consumed there.

An immediate action the Punjab government can take is to ask that for at least these 2 or 3 months, imported diesel can be supplied to Punjab as opposed to being used in Karachi, because Karachi does not have serious air quality issues. Or, they can import a higher quantity of diesel and use it in Karachi in addition to selling it further north. In this case, the diesel that we produce locally can be saved for the rest of the year. Our local refineries have their own containers and tankers, which can hold the fuel for a couple of months.

Mariam:

Is there any possibility that our local refineries can be upgraded to make better quality fuel?

Dawar:

No, that's not possible. We would need new refineries, and no one is going to invest in a new refinery now given that the entire world is moving beyond crude oil.

Mariam:

The claim has been made that even the higher quality Euro 4 or 5 petrol that comes into the country gets mixed with the locally produced petrol, which has a lot more impurities and a much higher sulfur content. Is that true?

Dawar:

Yes. The white oil pipeline transports refined oil from Karachi upcountry to Multan, and then from Multan, the oil is transported in tankers. But because imported fuel gets mixed in with the local refined petroleum when being transported via the pipeline, it is no longer clean when transported upcountry.

Mariam:

So even though we are importing 70% of our petrol, which is high quality fuel, it gets mixed with the locally refined petrol, and almost none of the petrol we end up using is clean?

Dawar:

Yes, and this is petrol. As I said, Euro 5 Diesel doesn’t even come upcountry. Upcountry, you have three refineries that mostly produce diesel, so there is no large need for sending diesel up country. Diesel is used for all sorts of heavy traffic, and all generators (large factories such as cement, iron or pharmaceuticals will be running large generators). Gas is no longer available for a lot of them, so these are either being run on diesel or on biomass, or maybe in some cases, they are using fine furnace oil as well. And furnace oil is even dirtier than diesel.

Mariam:

So all factories in Punjab are using this very poor quality diesel or in some cases, even dirtier fuel like furnace oil, for their power generation?

Dawar:

Yes, more or less, because gas is no longer available.

Mariam:

What about petrol? What are we using it for?

Dawar:

Petrol is used mostly in cars and motorbikes (and other vehicles). Outside of Punjab, in Peshawar and Karachi, for example, motorbikes and rickshaws still use CNG and gas. But in Punjab, they only use petrol.

Mariam:

So to recap, the first problem, which seems to me to be the biggest problem, is that the fuel we're using in Punjab, both diesel and petrol, is not clean. Even though we are importing much of it, none of that is making its way to Punjab.

Dawar:

Yes. The only Euro 5 product available in Punjab is high octane, because high octane is not produced in large volumes in Pakistan, where the market isn’t large enough for any refinery to seriously make it. All of it is imported, and all of it is transported through tankers.

Mariam:

How much do cars, motorbikes and rickshaws on the roads contribute to the smog? Is there a correlation between the number of cars on the road and the AQI at different times of the day?

Dawar:

In the transportation sector, we need to distinguish between two- and three-wheelers and other vehicles.

Because there is no public transportation, two- and three-wheelers are used extensively. There are around 5 million motorbikes registered in Lahore District compared to 1.7 million registered motorcars [source: Excise and Tax Department, March 2024]. Motorcycles use about 60% of the fuel in cities, and it can be assumed that they contribute similar emissions compared to cars, but that is only in absolute terms. Bike emissions are lower per capita and per km traveled than cars.

The Smog Mitigation Plan shouldn't just say that we need more electric vehicles; it is important that this increase in electric vehicles should be a replacement of the existing fleet. There must be an overall reduction in vehicles. One of the targets of the Smog Mitigation Plan should be how to reduce vehicles. Both cars and bikes need to be shifted to electric. Shifting bikes and rikshaws to electric may be easier in the beginning than shifting SUVs and heavy transport and buses.

In terms of AQI, AQI spikes are linked to traffic. In October and November, the AQI spike is usually around 7 to 8 AM and then again in the evening. In contrast, in December, when you have school holidays, the spike shifts to 10am. You can tell that schools are off and people are going to their workplaces later in the day.

There is also a meteorological angle to it. At 7 to 8 AM, the meteorological pattern is unfavorable; the pressure differential doesn’t exist for pollution to be dispersed.

Mariam:

One of the recent measures the government has taken is that school should start later, at 8:45 AM instead of the usual earlier time. Is that going to make a difference?

Dawar:

That won't make a difference at all. I think that's probably going to create even more issues, because now people might start aligning their office routines with school drop off. By the way, this wasn't part of the Smog Mitigation Plan. The plan did not outline that if the smog gets bad, the school timings will be changed. This is now a reactive measure.

Mariam:

A related problem we haven’t spoken about yet is the quality of engines in our vehicles. Can you speak a bit about that, how much of a problem it is, and how it needs to be improved?

Dawar:

In Lahore, we have a lot of old vehicles still on the road. For example, we have 50- or 60-year old buses on the road with engines that are repaired every few years, or they burn diesel without any controls. Similarly, we have cars that are 20 years old. Usually what cities have done is to impose a vehicle turnover policy. So when Beijing started cleaning up their air quality, they imposed an 8-year vehicle turnover policy. Delhi has imposed a 10-year vehicle turnover policy, which basically means that any vehicle older than that on the roads of Delhi will start getting very large fines, making the consumer sell their car to someone outside the area, or just, you know, retiring the car. At the same time, we have to make it difficult for people to purchase polluting vehicles, and encourage them to buy cars with the latest, cleanest technology available.

Studies show that after six or seven years, a vehicle's engine is so worn and torn that automatically, the efficiency of the combustion starts reducing. The reason is that there are chunks of waste that start lining the engine. And because the engine is old and inefficient, it starts releasing a lot of uncombusted material. This uncombusted hydrocarbon and black carbon (commonly known as soot), which is particulate matter, is then released into the air. There is also a lot of nitric oxide, a lot of nitrogen dioxide, and carbon monoxide. The emission of carbon monoxide from our cars is one of the highest in the world. So we really now need to have a vehicle turnover policy for most of Lahore district and to an extent, I think, Lahore division as well.

Mariam:

What happens if we get clean fuel in Lahore, but it’s used in these old inefficient engines?

Dawar:

There will be a reduction in the emissions, because clean fuel will make a difference, but the difference that it should be achieving won't be there.

Mariam:

We’ve spoken about some of the changes we need, but could you now outline some of the most important steps the Punjab government can take immediately which will have an impact, which they are not doing yet?

Dawar:

The most important thing to understand is that this is an emergency, and we need to take measures accordingly. We need to have cleaner fuel available in the Lahore division, the Gujranwala division, in this whole region. That will be the most effective measure.

The next step is that the planning for every sector must be done in advance, as opposed to taking reactionary measures such as last-minute school shutdowns. This has to be planned, maybe two or three years in advance of the education cycle, because you have to make sure kids have enough days in school as well [so they don’t miss out on their education]. For example, they can cancel spring holidays, and reduce the duration of summer break. Schools can begin on the first of August, for example, and then they can extend the winter vacation period.

At the same time. I think the morning start time issue has to be dealt with by either providing or imposing a bus mandate on schools, or the school day should start not at 8:45am, as they have decided, but it should start at 10am, when there is a higher chance of pollution dispersal. These changes should be made very drastically. For example, they have to cut down the school day, cut down the breaks (kids should not be playing outdoors) and winter vacations should probably start earlier. Kids can be given winter homework, or continue their education online, but it has to be planned well in advance.

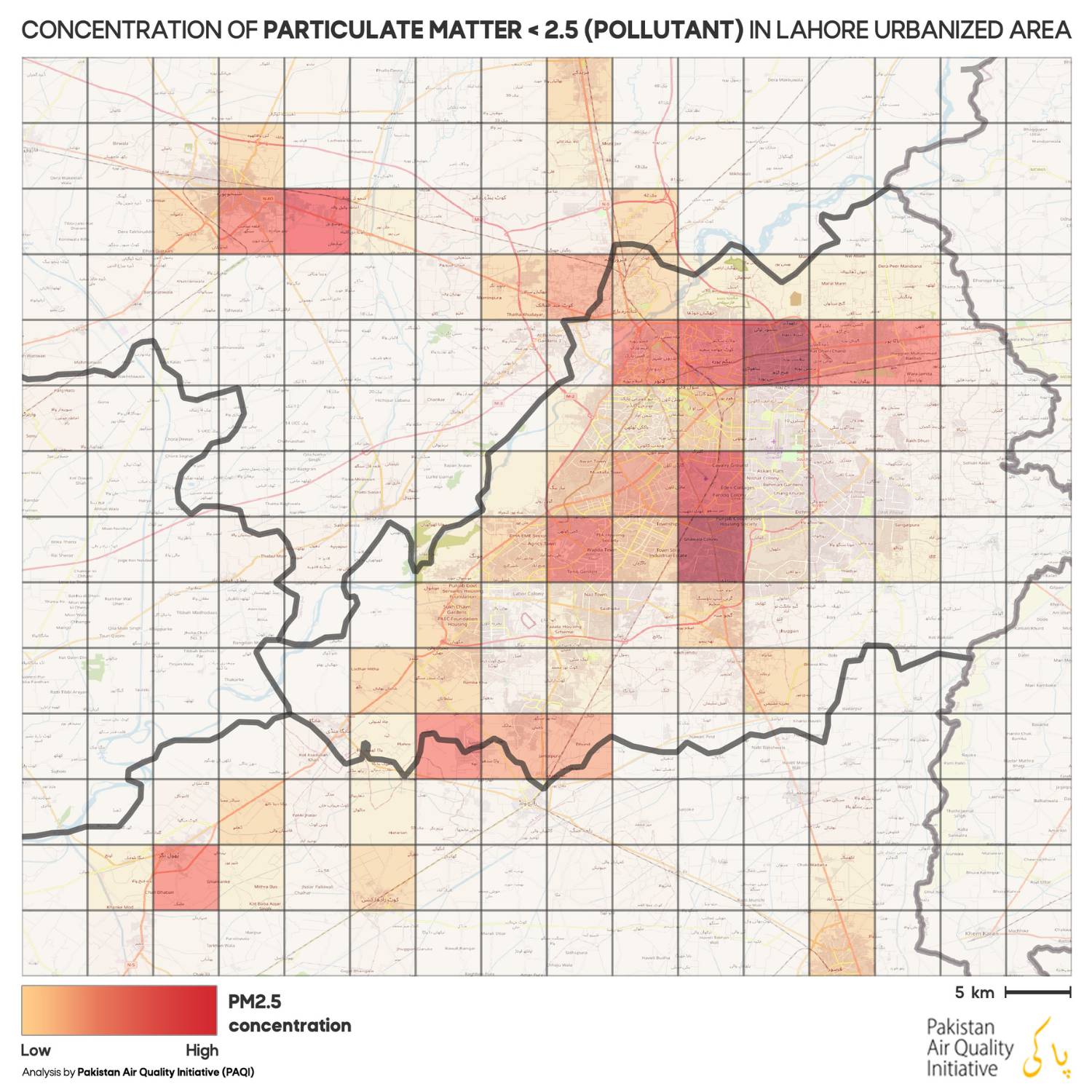

Next, and I’m very clear on this, they need to target offices as well. There's no way around it. For example, all offices on Main Boulevard should be shut and shifted to work-from-home. We have a big hot spot on Main Boulevard, and those offices need to be shut down as part of these measures. The government always asks what the [economic] impact of such decisions will be. Well, I’d say, the reason we have reached this point is because we always ask what the impact will be. So now we just have to act.

Mariam:

So in summary, we need fewer cars on the road, the school year and school timings have to be planned better to take smog season into account, and offices in high smog areas should be shifted to work from home. What else?

Dawar:

Another measure is that industry needs to be moved out of the city. China did this successfully. No one in Pakistan is having this conversation right now. We have areas in the north of Lahore, the stretch from Daroghawala to Batapur, for example, littered with unregulated industries. Everyone knows that these people pay off environmental inspectors and there are no serious checks on them. Similarly, in the south of Lahore, we have four or five big power plants that are very polluting. These structures have to be moved out of the city and replaced with something sound and sustainable, such as vertical rise housing instead of (lateral growth) housing schemes.

Mariam:

Are any of these measures included in the Smog Mitigation Plan?

Dawar:

No, nothing at all. There is nothing in the plan about anything [substantive] related to transport. The report states that a large proportion of the smog is caused by the transport sector, but there is nothing in the plan that actually outlines anything more than the need to shift to electric vehicles and the provision of clean fuel. There is nothing in there about how we can make that happen practically or administratively.

Mariam:

There are a lot of other ideas that float around every year with regards to reducing smog. One of them is artificial rain. Will that make a difference, and by how much?

Dawar:

It will make no difference at all. It didn't make a difference last year, so why would it make a difference now?

Mariam:

Planting trees?

Dawar:

Planting trees is not going to reduce the pollution in Lahore, but if you have large trees outside your house wall, they will prevent a lot of dust from actually coming to your windows, so they act as a barrier to an extent.

Mariam:

A lot of times, the smog is blamed on India. To what extent is that true?

Dawar:

There is pollution coming from India, and also going to India from us. So, depending on what the wind pattern is, either we are contributing to their poor AQI, or they are contributing to ours. So the wind pattern in the winter is predominantly from our side to India, and in the summer monsoon season, the wind travels from India to Pakistan.

Our government keeps talking about climate diplomacy in relation to India, but they actually have no idea what this would look like. What do we want the outcome to be? Because, very likely, India may say that our Punjab is cleaner than what is happening in Pakistan. Why do we need to do something?

Mariam:

Is that true? Is Indian Punjab cleaner than ours?

Dawar:

Their Punjab is cleaner.

Mariam:

Is it because of recent mitigation measures that they've taken?

Dawar:

Yes. In India, there is definitely improvement. It's marginal, not very drastic. But for example, we saw that this was the second cleanest Diwali they've had since the 2015 measures were imposed, such as the ban on firecrackers, and over there as well, people flout the ban, of course…

Mariam:

But I read some articles post-Diwali saying that Delhi was engulfed in smog because of it.

Dawar:

Yes, that does happen, but 5 or 10 years ago, on post-Diwali days the PM2.5 concentration used to be 800 micrograms and now it’s 650. So, that's an improvement. Our own improvement trajectory will be similar. I don't expect Lahore to improve from 800 to 200 over a year. That will never happen. We will have to wait several years for that improvement to come about. But improvement won’t happen at all with the current measures the government is taking.

Mariam:

The steps you’ve outlined are better quality fuel, a reduction in vehicles on the road, better planning for school closures, offices shifted to work from home, and more clarity on what climate diplomacy would entail.

Is there anything else that I've missed that you think people should know? Anything else that can be done?

Dawar:

I think there should be a mandatory order for masking immediately. And if you don't send your kids with a mask to school, they should not be allowed to enter the school premises. Everyone on a motorbike should be wearing a mask. It should be that serious. This is what Bangkok is doing, and their AQI only goes up to 200.

Mariam:

Is a proper smog mask necessary, or do surgical masks also work?

Dawar:

It depends on the quality of the surgical mask. There are some one-layer surgical masks in the market, which are not very good, but a three-layer surgical mask should be able to filter out much of the pollution. Ideally, of course, it should be an N95 mask, which fortunately has become more affordable.

Mariam:

You have said that we will have to wait years to see changes in the overall air quality, but when can we hope to get a respite from the smog this season?

Dawar:

We will get a temporary respite after rain, but as schools reopen, the AQI will shoot back up in a week or less.

Mariam Tareen is a writer based in Lahore. Her work has appeared in Dawn, Book Riot, Bustle, and Risala Magazine, amongst other publications. Mariam is the founder of The Writing Room, a platform for aspiring writers where she hosts writing workshops, interviews writers, and teaches children the magic and craft of writing stories.