Munir Hussain’s baithak used to be on Uncha Chait Ram Road, close to the famous Andaaz Restaurant, for those unfamiliar with the cacophony of narrow streets that make up Lahore’s Walled City. The road at one time was part of the bazaar infamous as Heera Mandi, but also called bazar-e-husan by Hussain and many others. And while Fort Road with its myriad of restaurants serving the same flavor of chicken tikka have thrived over the past decade as Lahore’s elite throngs to the area to partake in culture and rediscover the city’s history, Hussain was forced to shut down his baithak - an academy where he trained young musicians.

Munir Hussain Gujranwalia - as he is popularly known - started playing the harmonium when he was 11 years old, and has had the opportunity to play with some of the greatest classical musicians the subcontinent has seen. Around 20 years ago, he decided to take a backseat from live performances, and began to teach music instead. This is when he started his baithak.

For most of his life as the harmonium player he has been used to his place in the background, letting the vocalists shine. However, he insists: “It is the harmonium player who teaches music.” He sits in a dimly lit room in his house, and smokes yet another Gold Leaf cigarette. Hussain is old now; he can barely walk after a brain stroke a few years ago. This baithak was meant to be his final attempt to sustain himself through music.

This has been a constant struggle in his life: taking care of himself and his family through his craft. Hussain was taught music by his maternal uncle- his mamu - and he continued to practice and learn till the age of 18, when he got married. “I had responsibilities then. My nani, she gave my wife and I our own separate unit in the house - two rooms - and said now this [part of the home] is your responsibility. From that moment I was no longer a student, and I played to make a living,” he says. He earned his living by playing in the bazaar, with various ustads who had their own baithaks and mehfils, and by playing for the “bibian,” as he calls the female singers and dancers of Heera Mandi.

In the 70s, the bazaar was forced to shut down as a wave of Zia-ul-Haq led Islamisation swept the country. Hussain left and took to playing with the “bibian” in their mehfils in Dubai and England. He returned in 2002 and started his baithak, in the very area he started his career from, where things have changed significantly now. For one, Hussain doesn’t remember there being quite so many shoe shops and shoemakers.

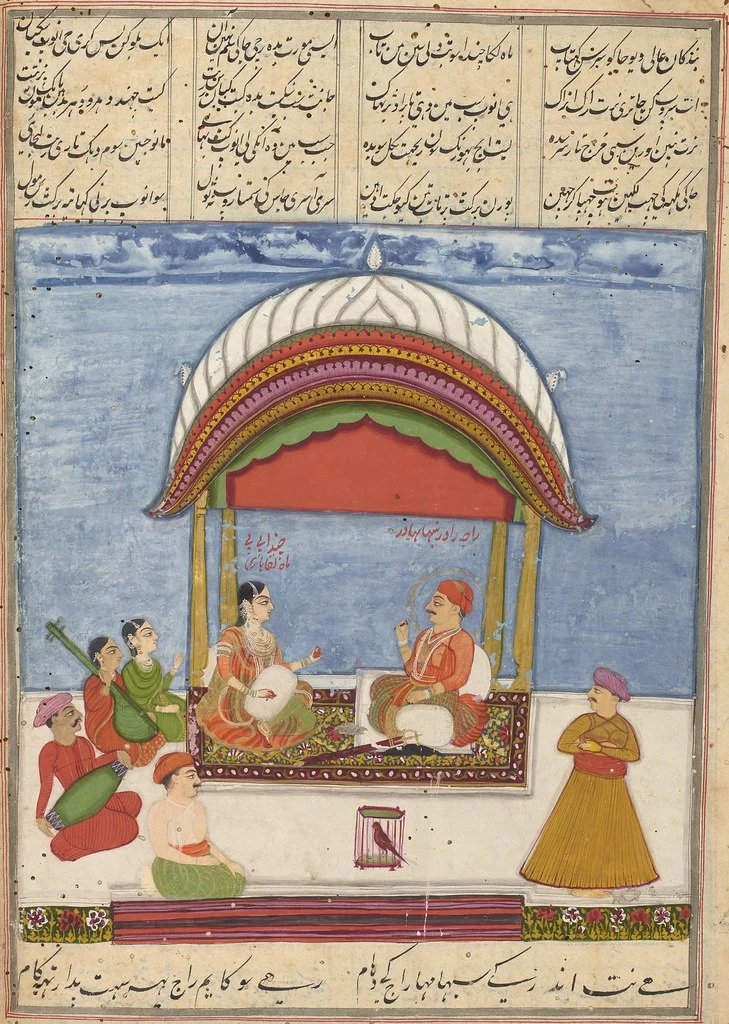

What he remembers is a bazaar filled with musicians where “a thousand rooms would open and people would come pick one they liked and sit there.” He adds: “There, you would find the great Ustads, the khan sahibs and the bibian, the women who would sing and dance as well. Then the doors would close and the performances would begin. Someone would be singing Urdu ghazals, someone would be singing in Punjabi, and another would be playing Bollywood music.”

Heera Mandi might have been famous for the singing and dancing women, but in the midst of all this, it was also the home to the tradition of classical music. The great ustads such as Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ashiq Ali Khan, Barkat Ali Khan all performed alongside the women. “Heera Mandi was known for its tawaifs, and playing for them was one way for the ustaads to earn a living,” says Kabir Altaf, a scholar of musicology and music whose Master’s thesis focused on the decline of Hindustani music in Pakistan post-1947. He names a number of female singers who also come from the bazaar, including Madam Noor Jehan, Farida Khanum, Naushad and Malka Pukhraj.

“It was under the influence of Victorian British values that this whole idea of we-must-save-our-music-from-the-dancing-girls came about,” says Anjum. Before this, these hard lines between tawaif and performer were not being drawn in the same way. He says this is where the idea of “respectability” also took root, as many of the female singers went on to reinvent themselves in their public lives and erase or at least minimize their ties to the infamous Heera Mandi.

The one clear distinction at the time though was that women were not singing the Khayal, that was taught only to the men. “The khayal, developed in the time of the British, was considered very serious court music and what we call pure classical music,” he says. He also adds that it was very late around the 20th century, around the same time as the idea of saving culture from the tawaifs came about, that the ustads started singing the thumri. “This was around the same time that they started cleaning up the thumri as well,” he says, adding: “The thumris had lyrics that would say things like oh my bed is empty which was then changed to something like oh the city is empty. The music had to be taken away from the tawaifs and the thumri was rebranded as something being about religion or God and not romantic love.”

And while this fight for morality might have started in Victorian times, the culture of the bazaar and the practice there by those who remember it did not draw these distinctions as harshly. The Ustaads still sang with the bibis and there was still a sense of community, which for most came to a halt in the 70s as people were pushed out of this community that they had created for themselves.

Ghazanfar Ali was a child when he started sitting with his uncle Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, during his riyaz and copying him. Although he was never allowed to sing or become a musician, Ali grew up in the streets around Mochi gate, and remembers the traditions of the time quite clearly. He remembers when as a young boy of seven on his way back from cricket practice, he snuck into the baithak of two famous sisters called Chimmo and Mimmo. “Ashiq Ali Khan was singing at the time, and Ghulam Ali Khan was also there,” he recalls. Ali can still hear the words Ashiq Ali Khan was singing, and sings them for us.

This kind of camaraderie was common; the musicians were a community. However there was also competition amongst them. Malik Nadeem Riaz, who sings Khayal, a pure classical form, says it was the competition that added to the musicians’ craft. “They had to attract an audience ultimately, and in order to do that they had to practise and be the best,” he says. Riaz talks about the famous competition between Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Umaid Ali Khan, that according to most in one instance took place close to where the famous chicken shop Arif Chatkhara is now. These kinds of impromptu concerts were a famous occurrence between the two.

Takiya Mirasiyan, which exists even today, is famous for having produced some of the most famous ustads of our time. In fact, only the best of the best would get an opportunity to sing at Takiya Mirasayian. A Takiya was traditionally a space built throughout cities like Lahore for specialized cultural activities, such as performing music, or discussing philosophy, or remembering God. Takiya Mirasiyan, is believed to have been built by the Mughal’s although the exact date is unknown, specifically to give the musicians a place to perform for the public.

It is these baithaks and takiyans that helped develop the tradition of classical music and its various forms, and Heera Mandi in Lahore being a central hub where the community of mirasis gathered, collaborated and thrived. The term mirasi has historically been used to refer to the community of people who are performers and artistes. It is also considered a caste in the subcontinent, and not one that is held in high regard.

The term for the most part has been used as a way to demean. However, in the past while most musicians tried to shun the label in the past due to its negative connotations, now they own it. Especially musicians like Hussain, Ali and Riaz. Hussain and Ali have grown up in musical families. While they always start the conversation making it very clear that their elders were God-fearing, religious minded people, and they themselves have stayed away from all kinds of vices, they also own where they come from and in some ways, want to reclaim their mirasi identity, demanding respect as performers and artistes. “Look at how they refer to mirasis,” says Ali, when asked why he was never allowed to pursue music at a younger age, or why his children didn’t enter the profession.

Ali says that it is this lack of respect for musicians is what ultimately led to the slow demise of classical music. Altaf pushes this demise much further back in time through his research and in a way verifies what Ali feels. “The entire moneyed class supporting the musicians were Hindu and Sikh. Classical music, especially in its pure form, was a high art and was appreciated by the rich, who had exposure to it,” he says. Altaf says that when the Hindus and Sikhs left Lahore at the time of the Partition, they took with them the patronage and appreciation of classical music. Those who took their place in the city did not have the means, or the taste, to become patrons. While semi-classical forms like ghazal and the thumri still found an audience, the khayal in particular became more uncommon.

Heera Mandi has now become synonymous with prostitution. Ideas of morality and respectability have made it difficult to imagine a world where the thumri was about a woman’s empty bed and where being a tawaif was a socially accepted position. Regardless of whether said tawaif slept with her patrons or not - it was all part of the culture. It was understood that not all women who sang were tawaifs in that sense of the word.

There is one thing that Anjum, Hussain and Riaz agree on though: in order to really revive classical music, there has to be acceptance at the state level that this is indeed part of the history and culture of this city. Anjum points to India where there is still an ecosystem that supports classical music. On the other hand, he says, in Pakistan “we’re still having this debate here whether music is halal or haram.”

Riaz goes a step further and says that the dancing girls were an important part of the culture and a main drawing point for audiences. He says “You tell the police today to stop bothering the women in this bazaar and the music will come back too.” He insists that the artistes and performers exist still, in the very lanes where once Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan’s baithak used to exist and now there is Phajje paye, where Noor Jehan used to learn to sing and is now a property dealer’s office, and what used to be Hussain’s baithak six months ago and is now a warehouse for shoes.

Amel Ghani is a freelance journalist based in Lahore, Pakistan. She also works as media trainer and consultant.

Twitter: @amelghanii

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/amel-ghani-9549a339?originalSubdomain=pk