Let me start by confessing that I have actively avoided making a trip to the UAE for most of my life, even when I have had reasons to induce me (a beloved aunt who’s made the UAE her home; proximity to Pakistan and so, until recently, more or less affordable airfare; a familial patina on the region’s otherwise imposing foreignness). A trip to Dubai more than a decade ago had convinced me that it was not my kind of place. Desperate as I am, most of the time in Pakistan, to walk about, I consider all my trips abroad as opportunities for using my feet – those relics of enforced immobility – to really get to know places. I like cities to be pedestrian-friendly and green. And I also like them to have human elements to them or to at least have those elements occasionally visible. A city is not a city if there is no gradient to its human-ness. If none of its special features are hand-me-downs. If it carries no threats to its own homogeneity, no glitch in its matrix.

A recent visit to the UAE, then, was a necessary affair, a means to an end. A lot, reportedly, had changed since I was last here. Abu Dhabi now had its very own Louvre, and Dubai boasted the world’s tallest building, a grey needle sticking out of its metallic weave. The morning after my arrival, I headed to the Louvre Abu Dhabi with the fragile lucidity of night-fliers. The sun beats down unsparingly on that land and although Lahore has begun to feel similar, I flinched at the mineral brightness. The architecture plays mirror to it until all is ablaze. It can appear, to the sleep-deprived, like a city from the Nights (One Thousand and One) – resplendent beyond logic, stunning stragglers into silence and capitulation.

The Louvre crouches low on an outcrop of land called the Saadiyat Island. In attempts to describe it, metaphors from the natural world abound. Upturned nest; a smattering of seashells; a pale crustacean pinned by the sun before it could hit the water. The museum opened to the public in 2017 – an exercise in cultural diplomacy between France and the UAE: You may lease the name of our most prized national asset for a very impressive sum; in addition, you can exhibit works from the collections of several prominent French museums; promise that it won’t be parochial in its approach. The building was designed by French architect Jean Nouvel as an homage to the domes and flat, segmented dwellings of traditional Arab architecture. The aim was to create a sanctuary-like space for great works of art – and the intellectual and spiritual growth they should ideally inspire – in a buzzing, modern city.

The roof or dome of the museum is undeniably its best feature. It is a multi-layered, meticulously engineered structure comprising thousands of star-shaped, aluminium-and-steel parts fused together. The effect is of some strange metastasis enacted in giant proportions over your head. The hard desert light is strained through the perforated canopy and rendered soft and ludic. It shifts and dances on a permanent, commissioned work by Jenny Holzer, just outside the galleries, and on a Rodin sculpture mounted high on a column. I found the Holzer easy to overlook, for her obscure inscriptions from historic Sumerian-Akkadian, Arabic, and French texts on a wall of marble can pass simply as an ornamental piece of salvaged history. To someone used to seeing her brazen, and nothing-if-not-intelligible, aphorisms in public spaces, it may come as a let-down. Still, beneath the dome, the marble glows with a numinous quality and, together with the lone, dark, Rodin torso suspended in front of it, the arrangement makes for a vaguely archaic, vaguely wise, tableau.

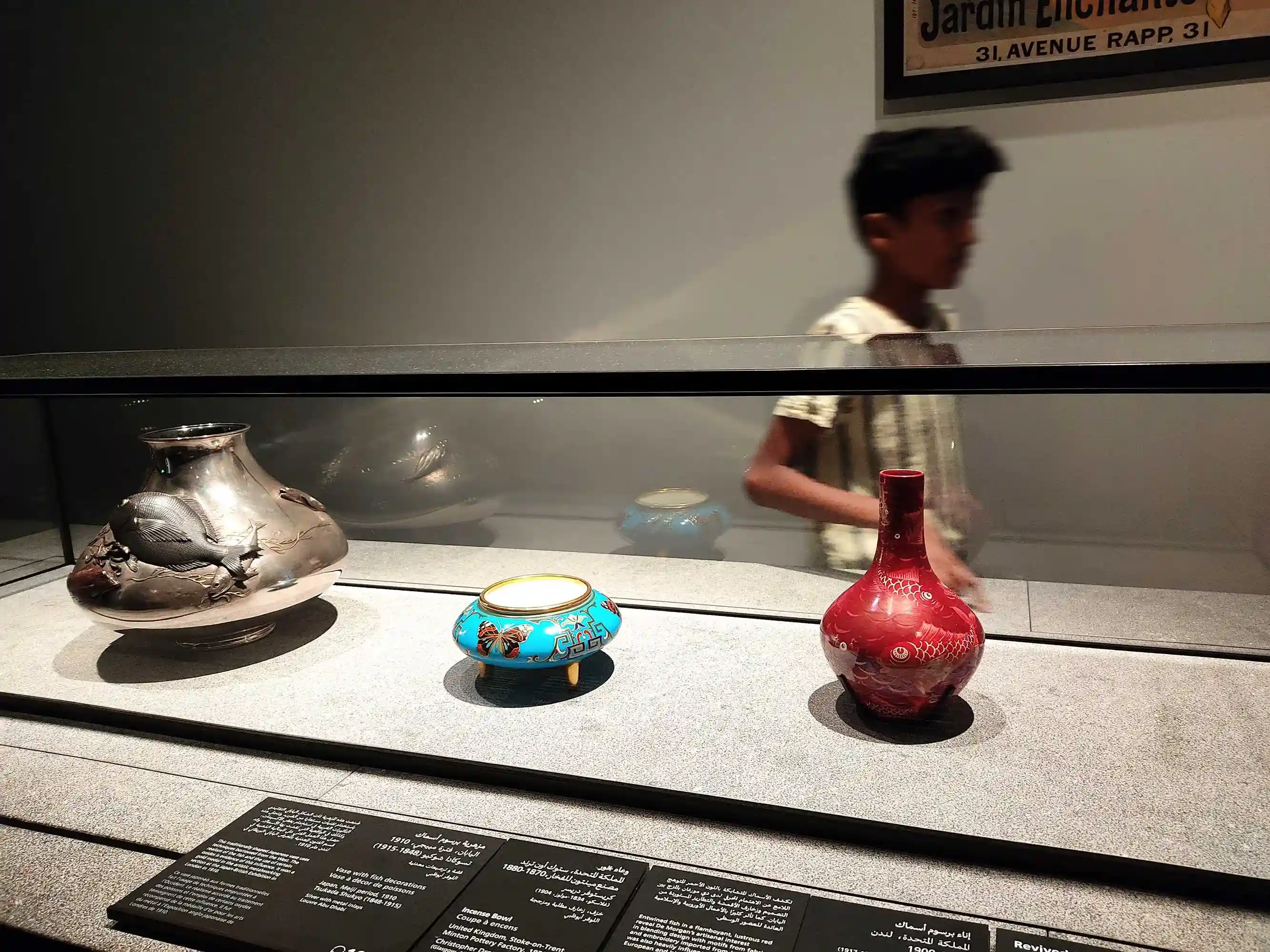

Inside the galleries, however, I found this quality of vagueness (the very quality of poetry, of involuntary meaning-making) to be sadly missing. The curatorial team seems to have taken an edifying and too-conscious interest in universalising the museum-goer’s experience of the collections. The galleries, divided both chronologically and thematically into broad, mollifying chapters (The First Villages, Civilisations and Empires, Universal Religions, A Modern World, etc.) are redolent of a classroom primer imparting complex histories as palatable lessons. The displays reminded me of those clever illustrations in Oxford History schoolbooks, where something from Mohenjo-Daro jostles something from the Roman empire, as each tries to fit onto an undulating ribbon of progress. Civilisations: A Happy Timeline. Usually, I find simultaneous histories and transcultural interactions fascinating but here, when I was confronted by these objects, each with its own aura, competing for views, it did not seem to work. It also did not help that the galleries are indistinguishable from one another and each flows uneventfully into the next, so there is hardly room – physical or imaginative – for reflection or reassessment, for any sort of inner grappling.

The problem is that while such an approach may be excellent for young visitors, for students who need to be guided into making simple connections between things, people, and events, it can become uninspiring fast for someone who may not have found themselves in a museum for a foundational course in world history by means of its art and artefacts. There are many reasons a person may choose to spend time with works of art. I have seen people cry in the presence of art, seen weary-looking faces nurse private wounds in front of a Rembrandt, seen people flit restlessly from work to work in no particular order, as if to order the contents of their minds. I have been these people at various points and in such moments have found myself desiring nothing more from a museum of art than to be a sanctuary – which the Louvre Abu Dhabi is touted to be. But sanctuaries need not strive so hard to offer respite.

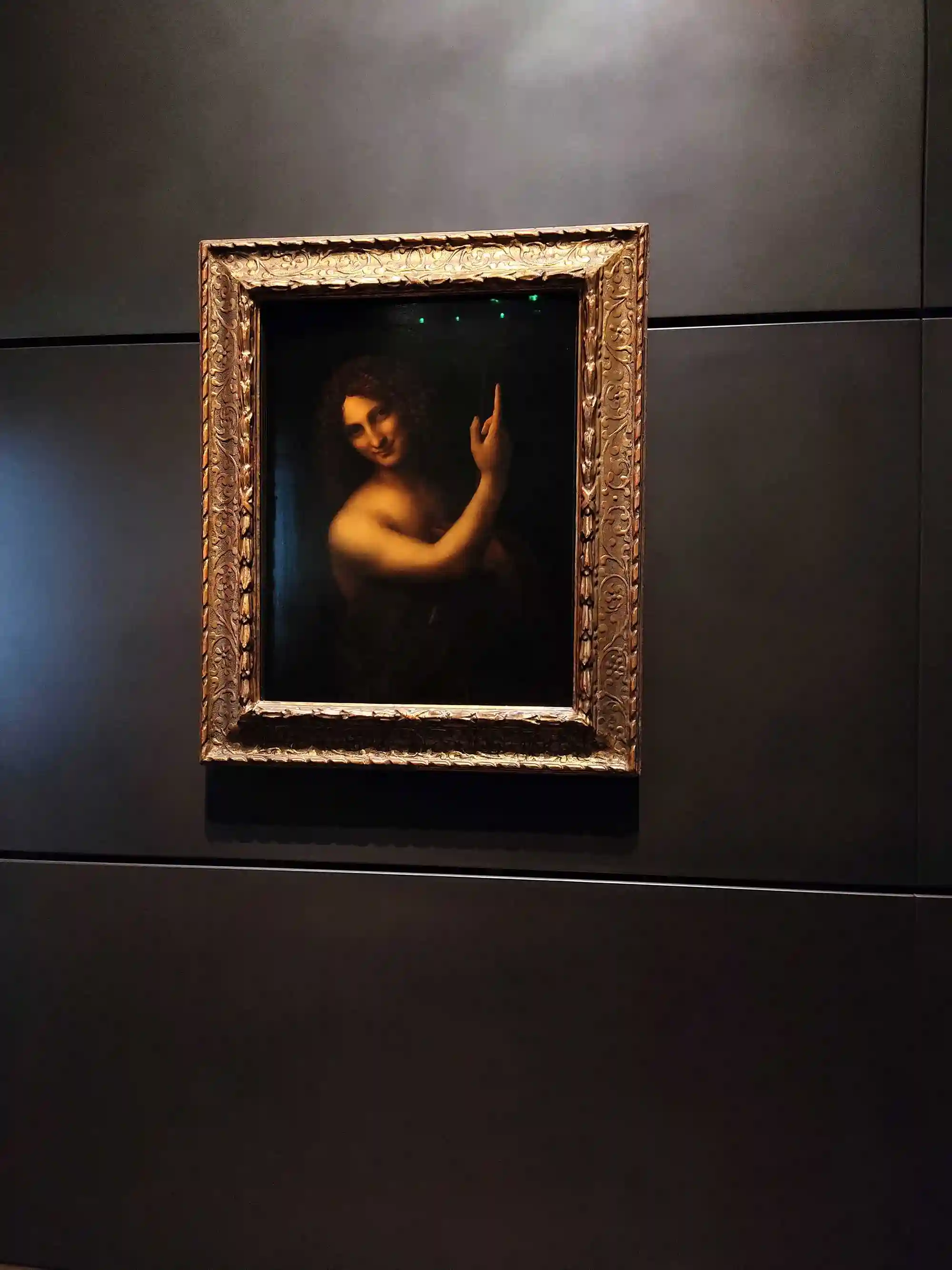

All this is not to suggest that some of the art on display could not soothe or transport. I was fortunate to re-encounter Leonardo da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist, on loan from the Louvre, Paris, where I first saw it ten years ago. A deep, personal association with the painting, made more profound by a fading memory of it, kept me milling about the work in its new location, in hopes of having it to myself and, perhaps, seeing it anew. It did not matter which of the galleries with their corresponding ideas it was helping round off (frankly, its “highlight” status rendered any relation it had to the curatorial scheme pointless), but because it meant something to me, I interpreted its being here now according to a private, and infinitely more compelling, symbology.

Faced in my personal life with a momentous change, the portrait, while retaining its original value on a purely technical level, struck me with the additional force of being a painting about incomprehension or certainly a painting that elicited incomprehension. My conscious mind fell back on a formal appreciation of da Vinci’s sfumato, deployed in the features, and the expert interplay of sharp and indeterminate that makes a simulation – on wood – so metabolic. But the rest of my mind, the great, lurching vastness of it, saw, in that feverish gaze, the look of someone who has been in perilous waters, a hair's breadth from death, and resurfaced with wry truths. I have seen eyes like that before, in the face of my father, when I was a child and he had a fever that had incapacitated him, constrained him to his bed and to a riot of thoughts beyond the comprehension of a child. Now those eyes were the saint’s eyes and my incomprehension was of a grownup who, despite fretting and planning, finds herself unmoored, uncomprehending of life’s designs.

I discovered, during the rest of my unavoidably streamlined passage to the exit, that I could come into such dialogue with or be moved or piqued by certain other works, but the galleries’ space and plan precluded real wonderment – or wonderment with an afterglow. There’s an essay on modernist architecture by J. G. Ballard, titled A Handful of Dust, that I’ve often recommended to my students as part of both art history and art writing seminars. I was reminded of the following excerpt from it, as I summed up the Louvre Abu Dhabi experience in my mind: “I have always admired modernism…But I know that most people, myself included, find it difficult to be clear-eyed at all times and rise to the demands of a pure and unadorned geometry. Architecture supplies us with camouflage, and I regret that no one could fall in love inside the Heathrow Hilton. By contrast, people are forever falling in love inside the Louvre [Paris] and the National Gallery.”

Later that day, as I headed skywards in one of the famously swift and mouse-quiet elevators of the Burj Khalifa (a generous present from my aunt and uncle, who would not hear of me returning without surveying the city from that delirious altitude), I thought of context, I thought of time, and how things out of both could still very much be rooted and present in individual consciousness. We were shown into the elevator by a young Emirati man in traditional garb. He was dour but beautiful, with such doomed features that I couldn’t help but see him as a kind of Majnun figure trapped in that desolation of glass. When we reached the viewing deck some 1821 feet above the ground, he was there before us, ready to gesture us through a boutique store onto the deck with a sad and graceful motion of his wrist. Here was a nice, odd, little thing – a glitch, if you will – that felt special and unique to my visit. Perhaps this is what some museums miss out on: letting people have their moments. I looked out at a tapestry studded with innumerable little jewels, making a design that was probably coherent but to me appeared as wilderness on fire. Inside, that melancholic man out-of-time waited for his charges, surrounded by miniature, galactic-looking models of his 163-storeyed desert.

Dua Abbas Rizvi is a visual artist and writer from Lahore, Pakistan, with more than a decade of experience in arts journalism. Her writings on art and culture, with a focus on South Asia and the arts of the Islamic world, have been regularly published in newspapers and journals of repute, including Herald, Dawn, The Friday Times, ArtNow, and The Aleph Review. She has also contributed essays to Encounters: The Art of Interfaith Dialogue (Brepols), the Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception (De Gruyter), Image Journal (for which she serves as an editorial advisor), and Selvedge Magazine. In 2022, she was awarded a South Asia Speaks Fellowship to develop her first book of visual nonfiction: a graphic memoir.