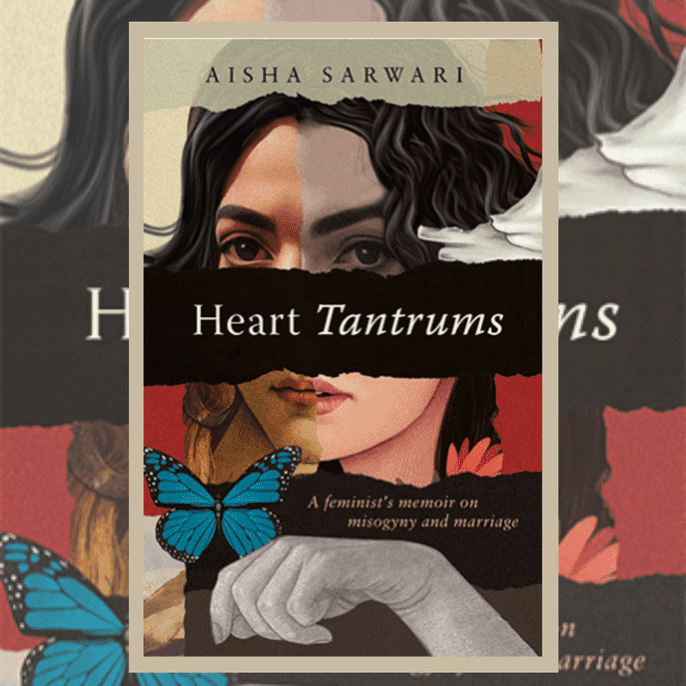

Ifeel like falling in love, sings Beyonce in the opening of “Cuff It”. I’m in the mood to fuck something up. And with her searing memoir, Aisha Sarwari sets out to do just that. Could it be the season of the Pakistani millennial memoir? Komail Aijazuddin’s Manboobs (wry, poignant and laced with his trademark biting wit) took Pakistan’s reading set by storm. Noreen Masud's A Flat Place was another absolutely unique absorption; pared to the quick like the bones she likes to collect, with the same startling, elegant aspect. Heart Tantrums: A Feminist’s Memoir on Misogyny and Marriage (Liberty Publishing, 2024) is in a similar vein as far as being unsentimental and clear-eyed about the past goes, but occupies a territory on the other end of the life spectrum. Perhaps it’s a sign of our age; millennials are hitting forty and have finally fallen in love with themselves, and now we’re in the mood to fuck things up. Perhaps post-Covid we’ve realised that life is short, and we’re halfway through it. We’ve had enough therapy to understand we won’t forget and cannot ignore, so perhaps it’s more healing to bear witness instead.

In spite of the fact that the book is preoccupied primarily with disease, caretaking for the sick, domestic violence and death – happy families have no history – Sarwari’s book is affirming in the best way possible. Look, it says. There is no one way to be a family, there is no prescribed way to love someone. Look, it says, opening the doors and windows to Sarwari’s life with a brisk lens we are invited to look through: unflinching, unsentimental. Haven’t we all, in one permutation or another, been perched on top of a jungle gym in a park in a foreign country, stoned and desolate? Haven’t we sometimes found ourselves in a life we wanted to burn to the ground – but took the kids to the dentist, went to work, and made dinner instead? Heart Tantrums goes where no Pakistani woman has gone before: straight into the heart of what it means to be a desi woman, without the safety from curiosity and distance from pain fiction provides. The snitch cousin, the hysterical accusatory mamoo and khalas: all real. The creeps at work, the crying in the bathroom: real. Living with a difficult man and being held to account for his misbehaviour, loving him in spite of being supposed to know better: real. There’s a reason why we don’t write memoirs, and Sarwari has walked directly into every one of them with the same try me energy to life that permeates her book – and it works.

_11zon.png)

Heart Tantrums spans most of Sarwari’s life. Amongst other things, it is an excavation of marriage, hers and her parents’. She writes of her childhood in Uganda, growing up Muslim, brown and less well-off than her relatives; a combination for minor disaster. Her account of life in Uganda describes a landscape and context unfamiliar to most, and perhaps this is one of the exceptional things about the memoir itself: that Sarwari’s life seems to have been different from the get-go, but the heart of the difference beats the same as anyone else’s. So we meet her insular, proud Konkani maternal relatives, who are Indian; we meet the Pakistanis in Uganda. Being Muslim unites them; being of different countries does not. You don’t have to live in Kampala to understand, and you can also be beguiled by the jamun tree, a beloved and specific representative of South Asia, growing large and fruitful in a university housing compound. Sarwari observes her much-loved mother and father as an adult, in hindsight, but also with her inner child vulnerably present in her longing and confusion. It is one of the hardest things we do in our passage to adulthood, witnessing our parents as fallible humans and learning to accept the loneliness of this knowledge whilst loving them in their authentic entirety, not as icons on a pedestal. This is probably the same longing we bring to partnerships; the desire to idolise the person who loves you, to bask in the complete complacency of being the centre of a romantic life. Millennials were raised by parents who had no such notions of marriage, but we grew up thinking we could change that. We had the internet, we had e-mail and chat rooms and could develop relationships that were as much of the mind as of the heart; we didn’t necessarily need to be arranged into marriage. Sarwari’s description of her husband messaging her on a well-known desi writing website will be a familiar feeling to many of our generation: the thrill of the MSN Messenger window pinging, the many-KB email sitting in your inbox. We thought we had an inside path to romance, and in a way, we did. But what do you do when your husband changes, and it’s nobody’s fault because he has a tumour in his head that is skewing everything you hold dear about him? How does someone in their early twenties begin to figure out these enormous things in life, let alone in a country you’re meant to belong to, but don’t have any actual connection to? What does marriage mean when none of the rules apply, and the lines between caregiver, mother and partner blur into a mess; when your parents don’t really have answers either because their marriages never had the expectations ours do? One memoir cannot answer the question. I suppose the best we can do is share how we’re trying to figure it out for ourselves.

The book makes no bones of the complexity of the choices we make, nor does it try to gloss over the joy and suffering contained within it. Heart Tantrums is also very much about the cost of caregiving for a terminally ill person, of being a woman who is her family’s primary breadwinner, of being a working mother, of being a fatherless daughter. If the book is intense, it’s because these experiences are, and more often than not, dignity is associated with silence. But Heart Tantrums is that conversation you’ve wanted to have with the author, with your neighbour, with the mom at school you’ve chatted with for years, your cousin. It’s the oddest dichotomy, the need to control a narrative, to present a curated front to the world, juxtaposed with the easy candidness one often encounters in female spaces. I have, countless times, been casually offered private details about a life from a woman over a cup of tea, in the waiting room at the gynaecologist, on a plane. We’re bursting at the seams with wanting to talk; whom does it serve to hold back? A woman who talks about herself is letting the side down, airing dirty laundry, shaming her family. Women who talk too much are problematic, too gossipy. As a feminist and writer, Sarwari must have considered the implications of speaking, of truth being seen as gossip and vice versa. As a feminist and writer reading Heart Tantrums, I know I’ve considered it.

A memoir is not a definitive truth after all, but a version of events as experienced by a singular person. Memory is variable; siblings raised in the same house will remember their shared family experience in their own individual ways. But to think that Sarwari considered, and persevered anyway, sounds like a clarion call. Heart Tantrums is a welcome, intense departure from the usual safe memoir older men write to describe their path to success. To paraphrase Ellen Bass, it’s about living your life even when you have no stomach for it; of doggedly showing up to your grief and joy.

Mina Malik is a writer and poet based in Lahore. She is the co-founder of The Peepul Press and prose editor at The Aleph Review.