In Sultana's Dream, the men are locked indoors, in the mardana.

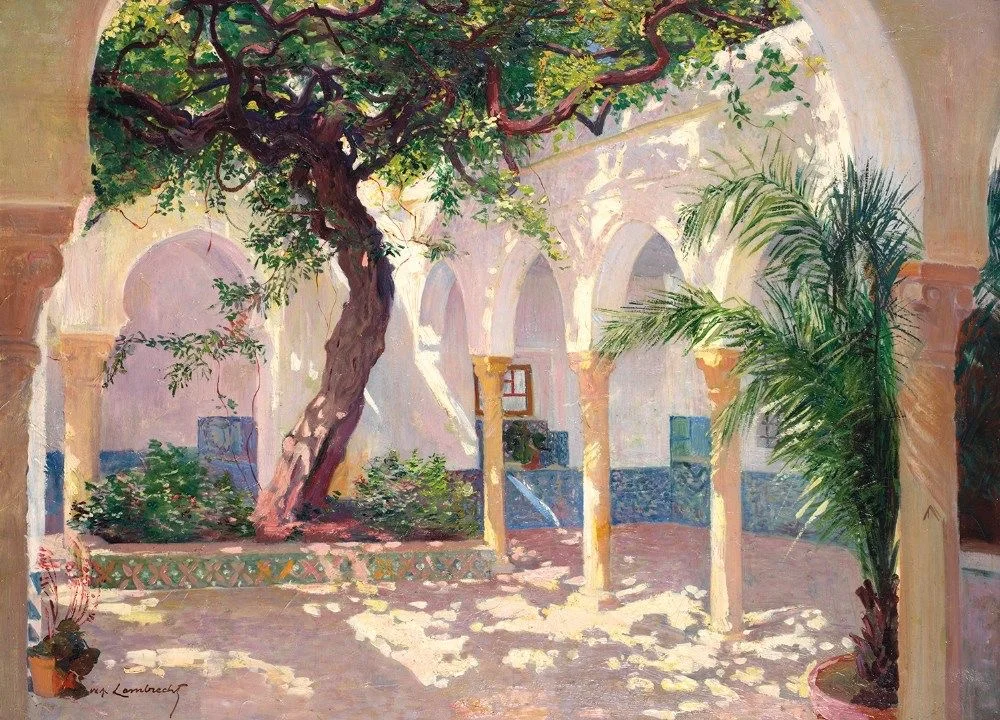

It is 1905, and Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain is dreaming up a world reversed — a utopic fantasy that takes the male-ordered world outside Sultana's dream and creates a pocket of time where everything is led by women. Sultana wakes (or thinks she wakes) into a city that is entirely unrecognisable to her. Dazed, she walks through streets, wide-eyed and brimming with trepidation — after all, these streets have never quite belonged to her. The sky eludes her; sometimes it’s strewn with stars, with the moon visible through the open window and at other times, the morning sun seems to shine bright, almost as if it has always been there, simply waiting for her to step out. Women here, Sultana finds, walk unhurried under the sky, their faces bare to the sun, chatting with other women, and working in laboratories, once considered to be the domain of the very men that are now locked up. The gardens spill over roses, the air smells of jasmine. All around, these laboratories yield new scientific innovations: flying cars move without sound, water is drawn from clouds and solar energy powers everything, from kitchens and carriages to whole cities. Men are peripheral characters here, mentioned briefly but never quite seen, shuttered away, and too easily won over by passion for the city to ever rest easy. The women of Ladyland have adopted this communal logic, and decided it is simply safer this way.

“How did you build all this?” Sultana asks the woman she had mistaken for Sister Sara, a stranger to her (though it hardly seems to matter here). “We do not deal in politics,” is the reply. “Our hands are clean.”

How did you build all this?

Begum Rokeya faced the dilemma common to reformers of her moment: how does one trudge through colonialism’s muddy waters without reinforcing the assumption that the subcontinent was a barren land, waiting to be delivered from itself? She works with (and around) this knowledge — she is writing in English, after all — and reaches for the master’s tools anyway, to create a world anew, where the zenana is not destroyed, but instead, upended.

Begum Rokeya Sakhawat, a Bengali feminist writer from British India, who wrote the feminist science fiction novella, Sultana’s Dream, for the Indian Ladies’ Magazine in 1905, was also asking this question of her own world. Across the subcontinent, communities were confronting a colonial order that had unsettled their ways of being and existing. Such interruptions demanded that communities reconstitute themselves within these shifting structures, negotiating their own place within them. Begum Rokeya was doing something similar, but complicating the terms of this interaction. The magazine (founded by Kamala Satthianadhan) had an editorial vision that provided the perfect stage for this reimagining, treating speculative and experimental writing as a kind of political act itself.

And yet, Begum Rokeya’s utopia wasn’t spun out of wispy threads of imagination alone; it rode the same wave of progress that colonial modernity promised to bring to India, following a script which framed science as salvation and civilisation as a rescue mission. Begum Rokeya faced the dilemma common to reformers of her moment: how does one trudge through colonialism’s muddy waters without reinforcing the assumption that the subcontinent was a barren land, waiting to be delivered from itself?

She works with (and around) this knowledge — she is writing in English, after all — and reaches for the master’s tools anyway, to create a world anew, where the zenana is not destroyed, but instead, upended.

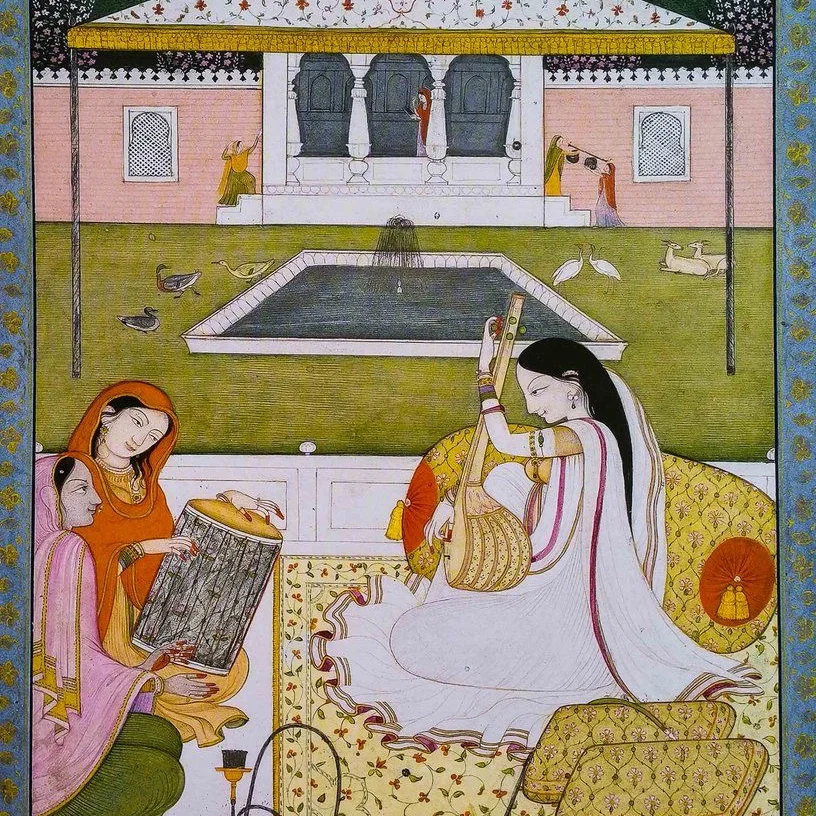

This transformation takes place against the background of the aangan — the open courtyard that acts as both the architectural and metaphorical heart of the South Asian home. In the traditional South Asian imagination, the aangan was the site of ‘small’ history, representing the mundane struggles of bills, marriages and meals that persisted, even as national revolutions thundered outside. Begum Rokeya takes this patch of private sky, which is also arguably the only ‘outside’ a woman could traditionally claim, and expands its horizons until the walls of the home disappear altogether, becoming, instead, a porous threshold that allows women to not just be bystanders at the helm of a shifting tide, but active participants. In her hands, the aangan is transformed from being a site of seclusion to a sanctuary that becomes the blueprint for an entire city. By the nineteenth century, the aangan had become a deeply political space, a laboratory almost, for reformers, nationalists, colonial administrators and laywomen alike to contest, produce and remake different visions and conceptions of womanhood.

The domestic space had been written and rewritten multiple times and it had been the foremost concern of male reformers decades earlier as well. It was, in many ways, the center of the nation (a ‘watani markaz’, as Margrit Pernau puts it), positioned as the place where the emotional foundations of a Muslim society could be effectively laid. The aangan was to become a fortress, a refuge where Indian women rescued colonised men from the emasculating experience of colonialism through the quiet rigours of their own devotion and self-restraint. The most influential technology for this project were stories that were meant to resemble instructions — literature that entered the zenanas as a wedding gift and sought to shape the minds of young brides (‘reformed’ women), offering them models to live by and cautionary figures to avoid. Nazir Ahmad's Mirat-ul-Uroos (1869), among the earliest and most popular Urdu novels addressed to women, is one example of this.

The novel follows two sisters. There’s Asghari, who is a prototype for the ‘reformed’ woman, and therefore, virtuous, emotionally disciplined and skilled in household management, acting as a cultural shield for a community under siege. Akbari, who is deigned to remain in her sister’s shadow, is the antithesis: hopelessly inept, volatile and unreformed — she acts as a guide on how-not-to-be. She represents the ‘unruly interior’ — a source of domestic friction and strife, a symbol of the very past that the new ‘sharif’, respectable class was desperate to leave behind. This text is also interesting because it’s not just preaching, it’s also teaching through imitation. Young girls, for example, are drawn into the narrative to absorb the idea that they must strive to be like Asghari, and fear becoming Akbari, learning to tutor themselves into the routines and responsibilities of daily domestic life.

In Rashid Jahan’s work the aangan undergoes a clinical autopsy. Through her short stories, cuts it open, exposing us to the grim reality of what festers beneath the surface: the reproductive exhaustion of wives worn down by annual pregnancies that they have no way to refuse, the venereal disfigurement of prostitutes considered to be untouchable and the caste-based exclusions that leave lower-class women to die without care.

The maktab (the home-school), where Asghari teaches young girls, is reflective of broader masculine and cultural anxieties of its historical moment. It is the place where the wife becomes a pedagogue and the household becomes the curriculum, where girls learn not through abstract moralising, but through the texture of daily life. This includes receiving practical lessons on things like maintaining ledgers, expenditures, eliminating waste and managing family resources with thrift and precision, as well as supervising domestic staff. Simply put, the ‘good’ wife, in this scenario, is someone who teaches through her own example; she is a person of minimal interactions — measured in speech, in sync with the emotional tenor of the house and always prepared to adjust herself according to the household’s needs.

These lessons, while seemingly only practical, are more spiritual in their purpose. They’re meant to train young women to domesticate the nafs, pruning the unruly lower soul, until it submits. This lesson is conveyed through emotional investment in the story, encouraging the reader to ‘choose’ virtue of their own volition, when the walls of the moral world (of the aangan) have effectively narrowed down this choice. The novel, therefore, is not just meant to describe the reformed woman, it actively builds her from the ground up, grafting a new identity onto her.

In much the same way, Altaf Hussain Hali’s Majalis un-Nisa demonstrates how women educated within colonial institutions can make better wives and mothers, who can then spur the engine of reform within Muslim society. The heroine of the novel, Zubaida Khatun, for instance, is well versed in the Quran, Arabic, Persian, Urdu, geography, mathematics and history — and is also someone who provides an example to multiple women on how to be pious, virtuous family women.

Roughly 35 years later, around the same time as when Begum Rokeya was engaging in imaginative world-building through Sultana’s Dream, Ashraf Ali Thanwi comes up with Beheshti Zewer, a comprehensive instructive manual of Islamic jurisprudence that’s meant to guide the religious and domestic life of Muslim women. Cold water ablutions, regulated sleep, measured consumption, even the right way to cook a meal — these are all instructions contained within this manual that also borrows from the Indo-Muslim conception of selfhood. Emotions, in this understanding, were permeable, floating between persons, which made it all the more necessary to maintain a strict sense of control over the domestic space and all manner of social interactions.

This domestic sphere, however, was not a blank slate, awaiting instructions; it was a place dense with meaning, with life-cycle rituals, gift exchanges, midwifery, ceremonial gatherings and devotional practices that women had long organised and transmitted. Beheshti Zewer specifically elevated the status of the home ideologically, but maintained that it should be subject to male textual authority. Custom, then, was counter-shariat, a theological ripple disturbing the spiritual fabric of the aangan, which had to be mediated through the exercise of self-control. The aangan, in this framework, was a place of excess — one where women were constantly in danger of spilling over, of moving beyond control, and consequently, also a place where they were taught to master their own seclusion.

The domestic space had been written and rewritten multiple times and it had been the foremost concern of male reformers decades earlier as well. It was, in many ways, the center of the nation (a ‘watani markaz’, as Margrit Pernau puts it), positioned as the place where the emotional foundations of a Muslim society could be effectively laid. The aangan was to become a fortress, a refuge where Indian women rescued colonised men from the emasculating experience of colonialism through the quiet rigours of their own devotion and self-restraint.

Still, the aangan wrote back; the women inhabiting this space were actively engaging with those that were writing and thinking about it. Rashid Jahan, a contemporary of Ismat Chughtai, helped found the Angarey group, a collective whose 1932 collection of short stories proved so incendiary that it was banned within weeks of publication. As the only woman at the forefront of these changes (and a doctor by training), Rashid Jahan was more interested in questioning the suffocating basics of domesticity, bringing the grit of the hospital ward and the logic of Marxist politics into the heart of the aangan.

Here, the aangan undergoes a clinical autopsy. Rashid Jahan, through her short stories, cuts it open, exposing us to the grim reality of what festers beneath the surface: the reproductive exhaustion of wives worn down by annual pregnancies that they have no way to refuse, the venereal disfigurement of prostitutes considered to be untouchable and the caste-based exclusions that leave lower-class women to die without care. Rashid Jahan’s unique perspective distinguishes her from her male progressive contemporaries precisely because it’s not interested in flattening the aangan into a universal class struggle. Theory, for her, is not to be kept at arm’s length, written about from the comfort of a desk or a manifesto; it is lived, personal and embodied. This also explains why Jahan’s work often focused on staging encounters between middle-class women and lower-class women, in public spaces that only reinforce these differences. In Mera Ek Safar, Jahan gives us Zubeida, a middle-class narrator that reflects the prejudices of her own class to her. As Zubeida watches the lower-class Hindu and Muslim women erupt into a fight in her train compartment, she sneers, eventually collapsing into a fit of giggles. Meeting their probing, traditional questions around her caste and marriage with mockery, she flippantly claims to be a ‘chamar’, a joke that lands with a sickening thud in a carriage already divided, bench by bench, along communal lines. For Jahan, this ability to look down on these women, to treat their daily quabbles with amusement, is shaped by the fact of Zubeida’s position as a modern, sari-clad and college-educated woman. Their concerns, petty as they are, could never be hers, after all.

These contradictions were not just literary; they were also very much woven into the architecture of Jahan’s own life. Her father, Shaykh Abdullah, had founded the women’s journal Khatun, established the Women’s College at Aligarh and served as the Secretary of the Female Education section of the All India Mohammadan Conference. Reformist movements that championed the cause of women’s education (while maintaining a strict emphasis on purdah), provided the backdrop of Jahan’s educational trajectory. Educated in these institutions, Jahan was aware that this meant that the very projects that had made her a doctor, a writer and a woman who could move through the world, had also furthered the divide between women like her and women who were never allowed to be like her.

Where Begum Rokeya dreams of the aangan as a utopic city, still assuming an eventual return to the world as it exists, Rashid Jahan complicates the idea of the aangan as a sealed-off, private space. It is a product of the pressures and contradictions of its historical moment, and so, women’s memories of home cannot be understood simply as private family souvenirs. Home here is not a place of rest or comfort. In fact, its contours are defined by the impossibility of doing just that. In that sense, its inhabitants inherit a space that is constantly arranged, rearranged and then undone, existing at the intersection of home and history. Women of the aangan, ultimately, cannot and must not rest easy.