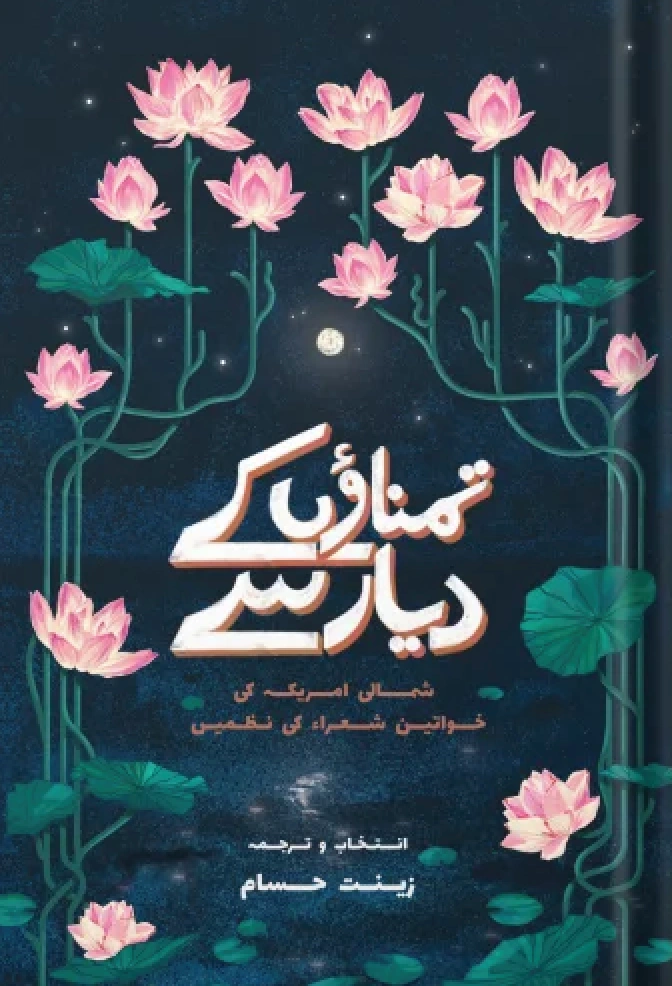

When Khusboo was published in 1976, Parveen Shakir was only 24 years old. She became an immediate literary sensation, a pioneer of a startlingly emotive poetics in Urdu free-verse that earned her debut collection Pakistan’s most prestigious literary award, the Adamjee. At that age, Parveen Shakir’s formal education in literature was limited to an English degree. Littered across her poems are allusions to Eliot, to Wordsworth, to the Othello of Shakespeare; just pages apart is a poem inspired by Yeats, then a poem interacting with the moment of the very first revelation in the cave of Hira. Other writers have also been successful at bridging influences from English literature within an Urdu, Pakistani poetics. Yet in discussing Tamannaon Ke Deyaar Se – subtitled as a collection that anthologises North American women poets, translated and compiled by Zeenat Hisam – Shakir is perhaps the most important predecessor to mark the fascinating innovations made possible when Urdu literary creatives have immersed themselves in English literature.

It is to advance engagements between the two languages and their poetries that Zeenat Hisam locates the need for her translations. Indeed, many of Shakir’s influences are still important throughout Pakistan and its English literature degrees; rare, however, are departments in which American or Canadian writings are being made subjects of study. Some are familiar: Emily Dickinson and her haunting hyphens; Sylvia Plath; Margaret Atwood; Mary Oliver. Among these reputed poets, Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘Filling Station’, which becomes the ‘Petrol Pump’ of Hisam’s treatment, struck a particularly heartfelt beat. Others are much more obscure; I was surprised to be moved by Linda Marie Stitt – apparently a poet of some renown in Canada – in reading her cheerful musings over ageing and life:

‘Vo sunehrē din kabhī bhī,

badan kē thē hī nahīñ.’

Of this particular anthology, discovering these more unusual poets is its great pleasure. Mehrin Masud-Elias, a Bangladeshi-American, ruminates over what it means to live an easy life in the imperial metropole, responsible as it is for unending wars, an exploitative economic system. Then there is Fatimah Asghar, a Kashmiri and Pakistani-origin poet; Hala Alyan, one of two Palestinian-Americans featured; several others, all who bring to the page unconventional diasporic reckonings being made by creatives practicing outside the spotlight of a White publishing industry. Iraqi-American Dunya Mikhail’s poem, ‘Maiñ Jaldī Mẽ Thī’, is one of the most moving poems in the entire collection, beginning with the sudden:

‘Kal maiñnē ēk mulk khō diyā.’

To read the collection in its totality, one does notice how many American poets have fixated on the imagery and symbolism of trees. But intersecting with these quieter meditations are resistances to Whiteness, to patriarchy, to the erasures of the indigenous, many of which make for exhilarating encounters in Urdu. Even more important, I felt, are the poems concerned with the body and its capacities for birth, for menstruation, for seduction — for even basic living and movement. The overt politics of some of these poetries may imply that their metaphysics is simple and straightforward, but I nonetheless found many of the poems included here to be wonderful, expansive journeys. In kind, I imagine many readers of Tamannaon Ke Deyaar Se could develop attachments to poets they have never thought much about, that may read to them as much more emotively powerful in Urdu than in English.

In discussing Tamannaon Ke Deyaar Se – subtitled as a collection that anthologises North American women poets, translated and compiled by Zeenat Hisam – Shakir is perhaps the most important predecessor to mark the fascinating innovations made possible when Urdu literary creatives have immersed themselves in English literature.

For a reader like myself, the use of a dictionary was necessary, especially as many of these poets are engaging with subjects and ideas that are not so common to popular Urdu. This is, however, also what makes Hisam’s work important, functioning as an invitation to a new generation of readers – and aspiring poets – to engage with the contemporary world and its experiences through the Urdu language. In fact, a lot of the poets here, such as Natalie Diaz (from whose work the collection acquires its title), are actively practicing, ‘new’ in how freshly they have become canonical in English poetry. I was not always interested in the observations of every poet here, but I admire the range of writers represented.

Within this curation, however, no Asian-Americans of non-Muslim origins are included. Hisam’s ‘North America’ is also notably restricted to the two countries mentioned above, a technically incorrect conception — though this did not dampen the compilation for me, as I believe in Hisam’s choices, in the resonances she determines as most productive for her undertaking. With poets I was more familiar with, such as Louise Glück, the strength of my relationship with the English meant that the pleasure of the poetry was for the novelty of reading it in Urdu, rather than for Glück’s sudden and soaring jolts of feeling. But I am neither very well-versed in poetry in English (I read most of these poems for the first time in Hisam’s Urdu), nor the wide reader of Urdu poetry required to make assessments of how these works could affect its creatives. For that, for those more seasoned reads and receptions, I suspect that this text may have yet to find its audience.

Why has it not? For one, the only launch event associated with the book has been limited to Karachi. But perhaps more importantly, it would appear that the space of ‘literary’ production in the Urdu language is shrinking. While the consumption of novels in Urdu may not be waning, these are the commercial successes of Jannat ke Pattay or Pir-e-Kamil – not the works of Naiyer Masud or Ismat Chughtai. This is not unusual: bestselling lists in the United States or the United Kingdom would hardly constitute Booker or Pulitzer winners. But there is a certain prestige which literary novels or short story collections acquire when they gain the prestige associated with a major award – a noticeable rise in sales, an integration into university reading lists, book-clubs. Through their English translations, even Banu Mushtaq and Geetanjli Shree have reaped the benefits of such audience expansions: from being a relatively obscure Hindi-language writer, Shree is now often the only translated writer of South Asia stocked in American bookstores; Mushtaq has travelled extensively in India, delivering talks well beyond Karnataka since her Booker win. After she won the Adamjee, Parveen Shakir went on to remain an unusually successful poet, delivering recitations not only in the cities of Pakistan, but also in the Arabian Peninsula, in mushairas organised by expat communities settled in petro-dollar booming cities and in the United Kingdom. The long-defunct Adamjee was, in fact, such a remarkable symbol of a writer’s quality that many of the books it awarded – Basti from Intizar Husain, Udaas Naslein from Abdullah Hussain, Lab-e-Goya from Kishwar Naheed – are still canonical to Urdu literature enthusiasts, both within and beyond Pakistan. Even Aag Ka Darya was an Adamjee winner; it is often called Urdu’s best novel, published when Qurratulain Hyder was still a Pakistani citizen.

I imagine many readers of Tamannaon Ke Deyaar Se could develop attachments to poets they have never thought much about, that may read to them as much more emotively powerful in Urdu than in English.

In contrast, neither the government-operated (and ambitiously representative) National Literary Awards nor the awards operated by the United Bank seem to attract comparable interest. This is excused as a situation of an Urdu reading public which is just not interested in serious contemporary literature. But this also feels like a failure of literary organisers, publishing houses, curriculum-developers and journalists in cultivating this public, in engaging with demographic niches in which reading and writing remain compelling pursuits. Although the imaginations of some at the helm of these institutions may suggest otherwise, these niches do exist outside of Karachi and Lahore. According to the anthropologist, Nosheen Ali, recitals surrounding Ghalib and Iqbal are some of the few spaces in which Muslims of different sectarian communities come together in Gilgit City. In the poorest districts of Pakistan, reading circles conducted by Baloch and Pashtun organisers are rapidly galvanising an emerging middle-class. In O- and A-Level student frequented literary spaces, like the Kitab Ghar of Lahore, poets like Parveen Shakir are being revisited, probed for their frank, enchanting articulations of desire. Outside the country, Pakistani-Americans – arguably the wealthiest of all Muslim-American communities – are conducting ticketed, sold out mushairas all the way west in Portland, Oregon. Even English-language poets within Pakistan, such as those affiliated with ‘The Dead Poets Society of Pakistan’, appear strongly influenced by Urdu poetics.

Yet one still wonders why this consumption of literature does not materialise in publishing successes. Zeenat Hisam’s work has not won such accolades, but even those that do not have their authors embarking on tours, their publishing or award success does not inspire the arrangement of reviews, nor are they sent to university professors. Sleep Journeys by Azra Abbas is a forthcoming publication in English, translated by Geetanjli Shree’s Booker-winning translator, Daisy Rockwell. It has also won an award from the University of Wisconsin-Madison for the quality of its translation. But is there any bookstore in Pakistan advertising this success, promoting its imminent release? Fahmida Riaz occupies the minds of more than a handful of South Asian graduate students in the United States; has the award-winning translation of Qila-e-Faramosh – The Fortress of Forgotten Ones in Sana Chaudhry’s English – even acquired a local publisher? And are there bookstores capitalising on these successes in translation reprinting the Urdu originals?

For a reader like myself, the use of a dictionary was necessary, especially as many of these poets are engaging with subjects and ideas that are not so common to popular Urdu. This is, however, also what makes Hisam’s work important, functioning as an invitation to a new generation of readers – and aspiring poets – to engage with the contemporary world and its experiences through the Urdu language.

Zeenat Hisam was a columnist at Dawn, is the translator of One Hundred Years of Solitude in its Urdu, is a labour researcher – her biographical experience suggests her engagement with American and Canadian poets would be curious to hear about. Given how many aspiring scholars and professionals from Pakistan migrate to the two North American countries of Tamannaon Ke Deyaar Se – are migrants in these two countries – perhaps reading figures like Bishop and Mikhail in Urdu can deepen their sense of belonging in these lands, among those peoples. As translations – and anthologies in particular – often involve more pointedly educational ends, I imagine that Hisam’s work would be interesting to many university departments within Pakistan; as does Yasmeen Hameed in a project of a similar spirit, Janoobi Asia Ki Muntakhib Nazmein, Hisam prefaces each poet with an explanation of why she has selected them, what makes their poetry singular. For readers who may not always be familiar with the movements and histories these poets are situated in, this makes Hisam’s work a great introduction.

As a text that self-consciously aspires to resuscitate Urdu literature and literary engagement in Pakistan, it is disappointing that Tamanaaon Ke Deyaar Se hasn’t achieved more circulation. In translating these pertinent, political and always emotionally-laced poems, Hisam establishes an important contribution to an Urdu literary space that both exists within and beyond Pakistan. But how will such works shape contemporary Urdu creatives – their poetries, fictions, their lyrics and their television scripts – if there is no space being carved for such texts to connect with these creatives? How will innovators as fresh and daring as Parveen Shakir emerge in this landscape? This remains to be seen.