“She loves me? No, no. I am ugly. I am a jester. I am not worthy of anyone’s love. I am here to make people laugh.”

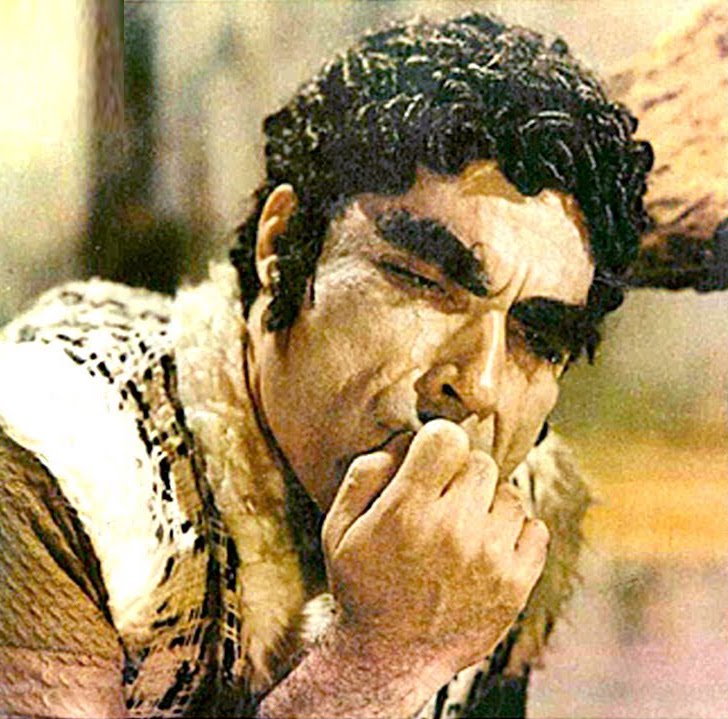

In Rangeela (1970), director-producer and comedian Rangeela plays Sohne, a character startlingly conscious of his own condition. The film opens with a dream—though we realise this only once he startles awake—in which he imagines himself as royalty, enthroned and enthralled by Nisho in a blonde wig, posed improbably as Anarkali. But even within fantasy, Sohne cannot sustain majesty. His Anarkali is not merely the tragic lover of lore but a conflation of Lahore’s everyday geographies: “You’re not just my Anarkali, you're also my Mall Road, McLeod Road, Mozang Chungi, Gawalmandi and Bano Bazar.”

When the dream ends and he must leave the village in search of work, his mother bids him a teary farewell. “Why are you crying? I am only going to the city, not Kaala Pani,” he reassures her, referring to the British colonial prison in Andaman and Nicobar Islands that once housed freedom fighters. While he is named Sohne (handsome), it is not until he confesses his love to Salma, the woman he has been seeing in his dreams, that he learns that he may not be quite as attractive after all. “Did you ever look in the mirror before thinking you could marry me?” Salma sneers at him, mere moments after introducing him to her fiancé. “Am I ugly?” asks a heartbroken Sohne.

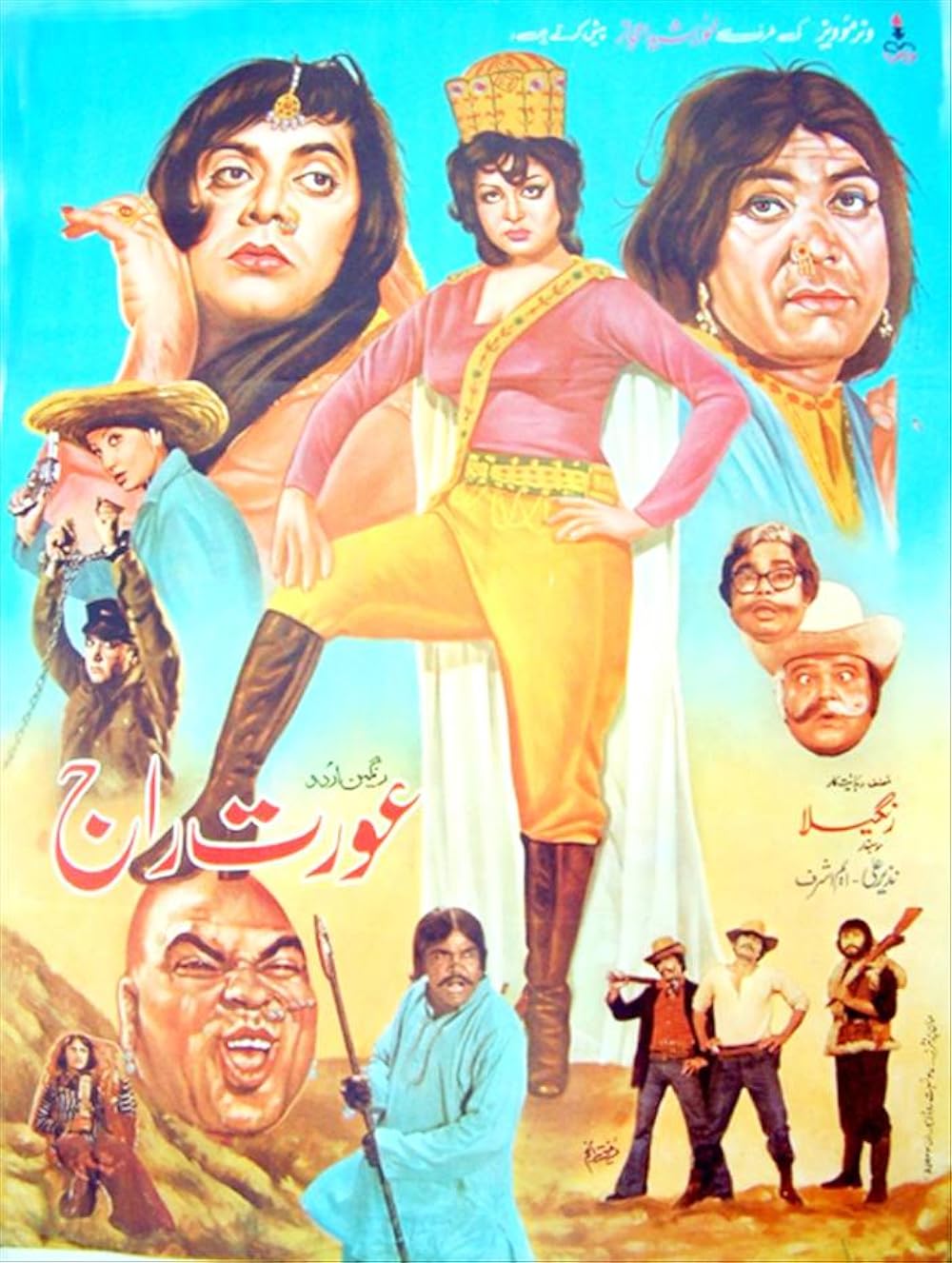

In the too-narrow strip of film criticism and journalism at home, Rangeela remains an underexamined figure. His more extravagant directions—Aurat Raj (1979), in which women revolt, seize power and transform every man into a woman—have attracted commentary, if only for their camp radicalism and their play with drag, gender and power. But the bulk of his work falls outside that frame, tucked instead into less politically charged titles: Diya Aur Toofan (1969), Rangeela (1970) and Kubra Ashiq (1973) (his adaptation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame).

Even a cautious appraisal can see Rangeela as a visionary director, returning compulsively to the figure of the outcast. In Kubra Ashiq, he becomes Quasimodo, literally, hunchback and all, losing Esmeralda to beauty, to another man, to fate. The tragicomic pattern recurs: Rangeela’s characters are undone not by circumstance alone, but by their ability to forget how others see them.

His humour was recognisable, almost too recognisable … his dialogues echoed the strange, specific jokes of family life, the kind that are funny only because they are not supposed to travel beyond the household. On screen, this proximity to real life was unsettling.

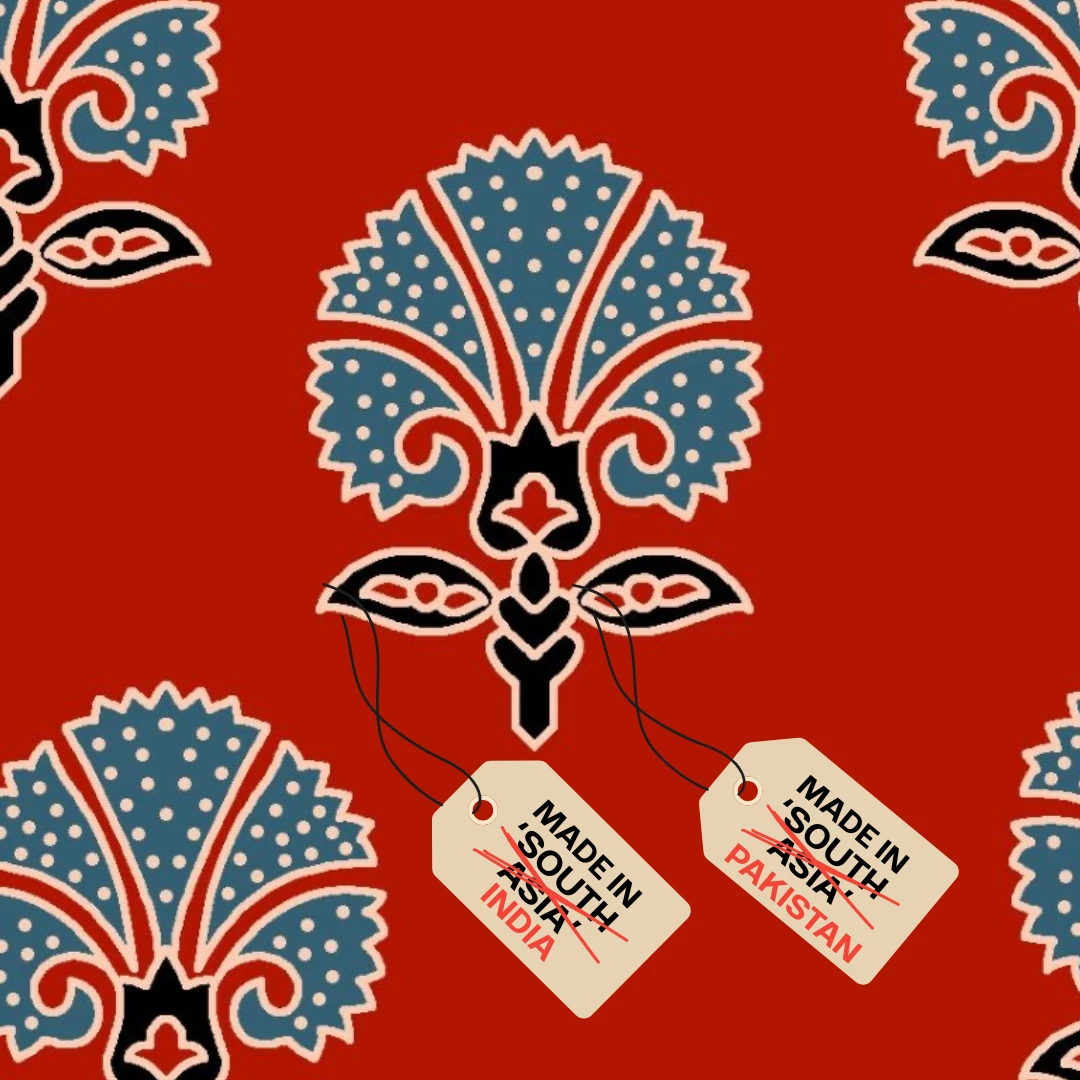

To trace him as a comedian is harder still. It requires sifting through a vast filmography of supporting roles, where he flickers in and out of plots not his own. The “social film”—that hybrid of melodrama, romance, action and comedy—was for decades the dominant form across Pakistan and India. As film scholars Ravi Vasudevan and Lalitha Gopalan maintain, its logic was to create an ever-expanding market: a film had to offer something to everyone. Rangeela was often absorbed into these composites, one fragment in a crowded whole.

Every now and then, YouTube channels devoted to Pakistani cinema exhume Rangeela with a blend of nostalgia and grief. The tributes are formulaic, Wikipedia in cadence: he rose to fame, made his fortune, squandered it on doomed projects like Kubra Ashiq and Aurat Raj, suffered further losses to marital troubles and poor health.

By the mid-2000s, when niche television channels such as Filmazia and Silver Screen began coaxing audiences back toward the forgotten reels of Lollywood, Rangeela had already ossified into the familiar. He was the revered name you did not quite know, the artist whose death required an obituary if you happened to work in news. This is the peculiar curse of mythologisation in Pakistani film writing: artists are celebrated simply for having existed, whose birth (and death) may be the most remarkable event of their lives. In the case of Rangeela, critics like Nadeem Farooq Paracha and Hassan Nisar circle endlessly around his “strange looks” and his equally strange humour, as though his career were a long rebellion against his own face. Perhaps this need to rescue him from himself is less about Rangeela than about the discomfort his comedy still provokes.

Paracha, for one, dismisses his supporting roles as “awkward slapstick antics devoid of any wit whatsoever”. The judgment does not arise in a vacuum and is reflective of wider impressions. To account for Rangeela in Pakistan’s comic tradition is to admit his difficulty of placement. His comedy was not always legible and he embarrassed not himself but his audience, which is a rarer, sharper feat.

I first encountered him in Hatim Tai (1967), screened as part of Filmazia’s marathon of films honouring Mohammad Ali after his death in 2006. I was seven, an age when everything induces laughter, and yet I did not find Rangeela funny. He appears as Fazlu, sidekick and foil to Ali’s solemn Hatim. Dressed in carnival regalia, with a crown sprouting horns and robes embroidered past parody, he enters with an announcement: “Wait for his majesty to arrive. These coins will make you rich and me, flat broke”. His master, grave and magnanimous, presides over ritualised giving; Fazlu punctures the solemnity with asides that register less as jokes than as reminders of consequence. “Lete jao, lete jao, humein khangaal karte jao” (“Keep taking and leave us penniless”). Hatim embodies the fantasy of inexhaustible generosity; Fazlu, its cost.

By then, I was already fluent in slapstick: Tom pursuing Jerry, Bugs Bunny tormenting Elmer Fudd in operatic drag, their lineage stretching back to Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Rangeela did not belong to that world. His humour was recognisable, almost too recognisable. He resembled my cousins, my uncles, that one Khala whose comic face-pulling could silence a room with laughter. His dialogues echoed the strange, specific jokes of family life, the kind that are funny only because they are not supposed to travel beyond the household. On screen, this proximity to real life was unsettling.

Contemporary comedy, whether in the shape of stand-up routines or PTV sitcoms in their prime, places the lead performer at its centre, the gravity around which humour coheres. Rangeela thrived precisely because he was not the centre.

It was a relief, eventually, when my loyalties shifted to television, to the tidiness of PTV’s genres. For a child raised on cinema’s sprawling hybrids, this was a recalibration. Television offered the opposite: stability, if not monotony. Sitcoms such as Guest House and Family Front treated comedy as a common language, jokes to be traded the next day at school. Dramas like Dhuwan and Dasht excluded such interludes by design. Conversely, Rangeela’s cinema was harder to translate, harder to share. What was I to do with a film like Meri Zindagi Hai Naghma (1972)? How to explain his advances towards a bashful Sangeeta mid-song, punctuated by the same grimaces he reserved for parody? I was already the child accused of taking films too seriously. How could I recommend a film whose pleasures were incommunicable? To narrate his humour in company would be to repeat the very unease he enacted against all codes of respectability.

On the Internet, now the more typical vessel of remembrance than obituaries or essays, fragments of television comedy circulate easily; sketches from Fifty-Fifty, repartee from Alif Noon, the verbal acrobatics of Loose Talk. Films of the same decades surface more rarely, and when they do it is often as kitsch: Anjuman and Ali Ejaz’s slap-happy courtship in Sahib Ji (“Tenu pyaar karna paein ga”); Naheed Akhtar’s glittering disco ode Some Say I Am Sweety from Kora Kaghaz (1978). What draws audiences now is the temporal gap itself—the earnestness of then, the cool appraisal of now. Online culture unfailingly promises to recuperate the camp and the cringe. But Rangeela resists such recovery.

Where Moin Akhtar, Bushra Ansari and Anwar Maqsood crafted a middle-class legibility through polish, and Umar Sharif and Iftikhar Thakur thrived on the rowdy directness of stage spectacle, Rangeela sat outside both traditions. He provincialised the grand narratives—history, romance, politics—by yoking them to the most ordinary frames of reference. No clip, neatly excerpted, can compress this vitality into something that serves the economy of social media.

Contemporary comedy, whether in the shape of stand-up routines or PTV sitcoms in their prime, places the lead performer at its centre, the gravity around which humour coheres. Rangeela thrived precisely because he was not the centre. He was nothing if not ubiquitous. And his excesses could not be contained. It is not quite slapstick, but a body unspooling into jest before language can corral it into a joke.

There is wit to be found after all, for those willing to see it, in trading comedic timing for embodiment. These perversions—yes, that is what they are—may have been the by-product of typecasting and exploitation, but they also signal the limits of the system that sought to contain him. To counter-read him as a cultural text is not to find resilience or resistance, but to encounter a structure too porous to erase him, too hungry to fully absorb his fleshiness.

To grow up with Rangeela was not to find him funny but to accept his inevitability: his face flickering from the dull rectangle of the family television, or else through the haze of low-resolution YouTube prints. The mise-en-scène dissolved into blur, colour drained into monochrome, and still, his face, in all its promises and possibilities, remained unmistakable.