Typically, American readers bristle if their favourite works are called “satirical”. Observing irony or commending a writer’s wit is one thing, but imposing the label of satire has a humbling effect: it declares that a work aspires to deliver gags, not literature. Yet, unusually for a satirist of American letters, Percival Everett’s accolades are various: in 2021, he published The Trees, a Booker-finalist; in 2023, a screenplay adapted from an old novel of his ended up winning the Oscar; now, for James, he has received both the Pulitzer and the National Book Award. In the form literary satire exists in the United States, Everett is a giant.

In Pakistan however, “satire” is not a pejorative. Our most brilliant novel in English – and the only to have the honour of being banned in its Urdu translation – is A Case of Exploding Mangoes. Its chapters featuring the late General Zia-ul-Haq are memorable; that the story otherwise tracks the homoerotic love-plot of two army servicemen has it take risks of no others before it. Years after its publication, through Punjabi and Urdu-language video columns uploaded to the BBC, the author Mohammed Hanif continues to take jabs at military and civilian elites. Within this creative strain, Hanif does not stand alone: clips from Geo’s Hum Sab Umeed Se Hain, as well as the older Fifty-Fifty and Ainak Waala Jin, occasionally resurface and become viral on Instagram; our most esteemed living playwright, Anwar Maqsood, remains committed to attempting funny historical retellings; and some stories of Manto, like Toba Tek Singh, and absolutely those of Ghulam Abbas, such as Aanandi, are palpably satirical in spirit. In our context then, there is a canon of provocation, of bitternesses diffusing through humorous prose: the standards are high, the precedents, abundant and exalted.

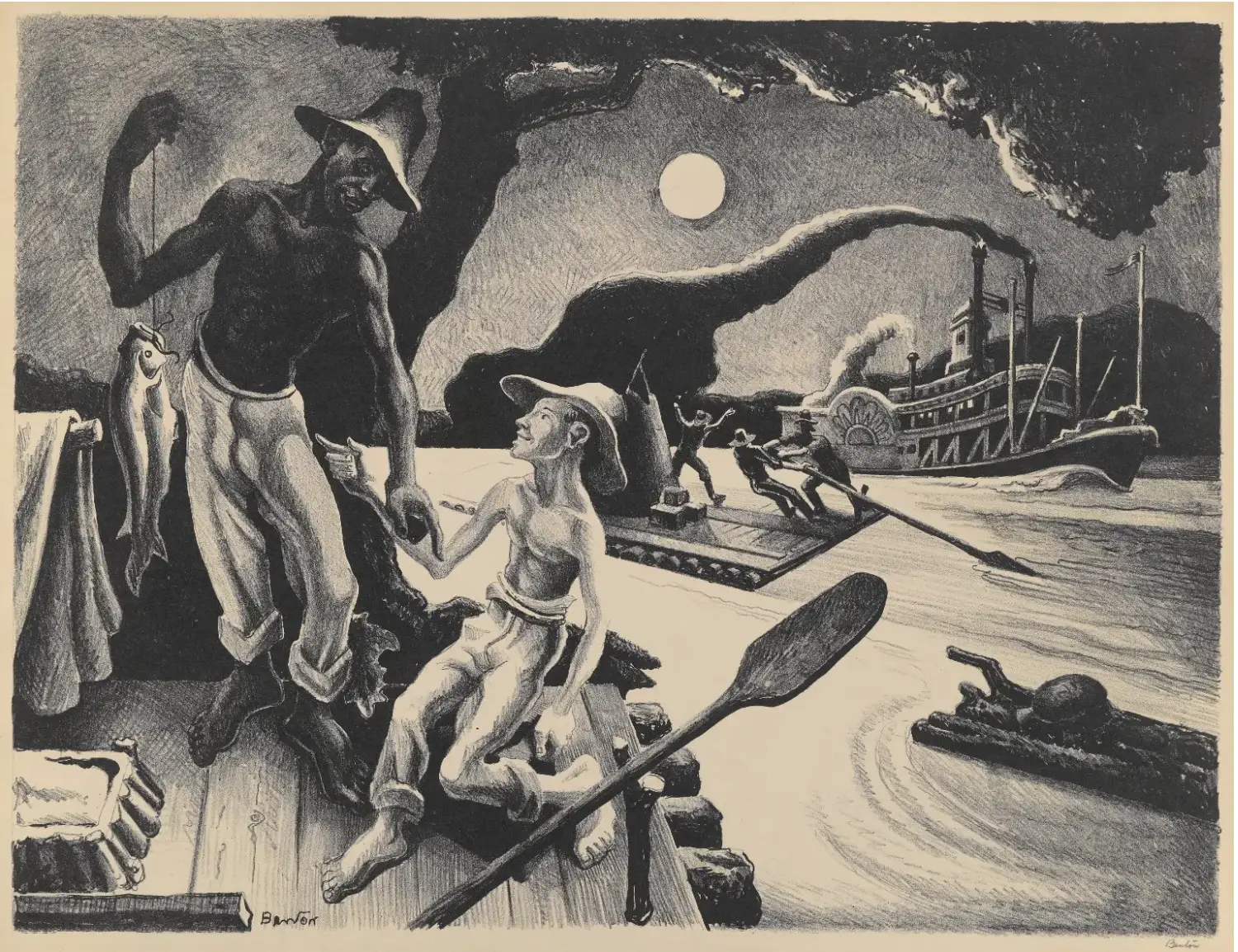

Mark Twain – the original creator of Jim and Huckleberry’s story of which James is a retelling – belongs to a much shorter list of canonical humourists. Huck, Twain’s hero and narrator, is not even beloved in the vein of other classic characters such as Oliver Twist or Elizabeth Bennet. Rather, in much of Pakistan, Huck appears in undergraduate syllabi – to teach students what is an “unreliable narrator” – as among the very few American characters discussed in English literature degrees. Jim is Huck’s Black, enslaved companion on the run. Together, they set off on a boat journey through much of the Mississippi River, which the reader experiences through Huck’s adolescent, oblivious, White perspective. Still, at the end of what is ultimately a light-hearted picaresque of disconnected, entertaining sojourns on land – and in spite of an ending which is happy, in which Jim is freed and Huck forced to become more conventionally educated – Twain’s remarkable achievement is that the reader walks away haunted, conscious of a range of violences let loose in the not so remote past of the American South. As social satire, written at a time when civil war had ravaged this region of the United States, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn must have been an exceptionally provocative work of fiction.

Percival Everett does something provocative too when he retells this particular story from the perspective of “James” – his elevation of the enslaved Jim. In the original, Huck tells many tall tales, fibs; in James, the reader is situated in the more sophisticated pantomime of a Black man trying to pass as what White southerners expect him to be: simple, docile. But in the transformation of Jim to James, Everett also gifts this character a complex literacy. In much of the novel, James hallucinates, wrestling with his Enlightenment heroes – Voltaire, Locke, Mill, Rousseau – resenting them for their liberal, shallow maxims. James also speaks and narrates this story in a more learned diction than Huckleberry Finn did in Twain’s book; it is only when he is proximate to White ears that he conceals himself, that he starts talking like the Jim of the original. Most other Black characters – slaves like James – deploy the same ruse in Everett’s world, speaking “properly” only when they are amongst themselves. If they are incapable of doing so, if the extent of their trauma and dehumanisation is too far gone, Everett has no interest in their stories: in a matter of pages, he kills them off.

Clearly, Everett prefers staying with the smart and well-read. In The Trees, his Mississippi murder-mystery, two Black cops from urban Hattiesburg and a Black woman FBI agent from Washington D.C. lord over White “hicks” from the countryside, mocking them for their diction, for their ignorances, for their “fake news” claims and Trumpisms. Though all these white characters seem very poor, and it is odd for these college-educated characters to mock them as much as they do, it is fine: these Whites have intergenerational connections to the Ku Klux Klan, to romances surrounding segregation, to the slavery-upholding Confederacy – their poverty is incidental to how vile they are. But where are the Black characters of these same rural hinterlands? For the most part, Everett presents them as corpses; there are two who are living, but they have some fantastical qualities that precludes them from any claim to realistic representation. Then, in American Fiction, the cinematic adaptation of Everett’s Erased, an unsuccessful novelist unable to sell his latest manuscript writes another one in an entirely urban, inner-city Black English. The novelist does this in a fit of rage, as a joke for his agent. Nonetheless, he becomes an overnight sensation, and is advised by his agent to pass off the manuscript as autobiographical. Everett, thus, parodies a literary world in which Black culture seems only interesting to a White publishing industry when it centers gangs and drugs, forcing the Black bourgeoisie to issue commentary on sociological crises with which it shares no substantive relationship. This is an interesting lament. In relation to James, perhaps more interesting is the novelist character's Southern domestic help-woman, a long-time employee in his parents’ Boston mansion. She is the most proximate to the inner-city social class with which much of the story is concerned. But her arc is low-stakes, her role generally limited to exuding maternal energies.

No wonder that Everett transformed Jim into James, turned him into an erudite reader with the sagacity of Frederick Douglass – he could not have worked with the Jim of Twain. Of course, James’ life is also full of drudgery, of hard labour and cruel lashes. But he – like many other such enslaved characters in James – also somehow makes the time to enlighten himself, to self-educate, to intellectualise. This leads the reader to even more hilarious retellings of the initial moments of The Adventures, in which a reader experiences familiar moments through a more acrid lens. James, like Huck, is thus an amusing narrator – although perhaps more so for one familiar with the original story, for one who can see what Everett is changing and why. But since the choice of replacing the child-rascal with a genius-in-hiding makes the journey through the Mississippi a far grimmer narrative than the original, this may be less satirical in effect for readers unfamiliar with the original. In fact, while the dialogue-driven slapstick of Everett’s other work is present in James too, it is ultimately more loyal to serious reckonings.

Unfortunately, these reckonings have already been made by writers with more compelling political and poetic commitments. One immediately thinks of the searing Beloved of Toni Morrison, which still ensnares readers in an intense, densely emotional chokehold as much as it did when it was first published in 1987. One also thinks of the lesser-known novel of Edward P. Jones, The Known World, from 2003. Within it, a reader is not transported to the already much condemned American South, or to a historical context mired by more present-day ideologies of whiteness and blackness, but to an ostensibly more liberal 19th-century Virginia. Here, the reader encounters Black slave-holders, Native American slave-hunters, Whites seemingly friendlier than those of the South, and also, a rich array of narratives drawn from the enslaved – both the literate, and the men and women battered beyond all comprehension. The Known World is a dazzlingly provocative novel, a text that transcends and redefines how we as readers in this literary moment engage with this history and space. This is not the effect of James.

But is this not the objective of satire: to provoke, to tread further than serious literature can? Certainly in Manto and Abbas’ sympathies with prostitutes, in Hanif’s Shigri and Baby-O, in the Geo skits of Pervez Musharraf telephoning George Bush before bed to tell the American President about his day, satire pokes at what others cannot. Satire is a mechanism to talk about who beat Saleem Shahzad to death; who sent Fehmida Riaz to seven years of exile in India; why Sajjad Zaheer was buried as an exile in what is now Kazakhstan – it can pose such questions, tongue-in-cheek. James, on the other hand, is posing questions that are the purview of op-eds, of popular cinema – that are the subject of other, more rattling novels. I cannot applaud it for observing absurdities dissected so powerfully in Morrison and Jones.

I suspect that in the United States, satire is imagined as an accessible mode to engage with complicated kinds of metaphysics. The Barbie movie serves such a function for liberal feminism; John Oliver and Jon Stewart for world news; James for the brutalities of American slavery. But this is a world that constantly parodies Donald Trump (Everett dedicates an entire chapter closely tracking him in The Trees), that hired Dune star Timothee Chalamet to mock pro-Palestine protestors; it is a world that gave an executive of the Gaza genocide, then-Vice President Kamala Harris, a chance to perform as herself in her very own SNL skit. When it wants to make provocations, when it seeks to make choices, it does. It’s just that these are – to put it mildly – rather tepid statements.

And close to the end of James, when Everett changes something fundamental about the relationship between Huck and Jim, I found myself disturbed by that choice. In a literary moment when so many children are being orphaned, so many men and women left as the only survivors of their families, that Everett’s imagination of what bonds might form between unrelated adults and children should be so conservative is almost infuriating. And while I am no enthusiast of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, I believe Mark Twain’s vision reaches much farther than Everett’s.