It is almost a rite of passage for a group of friends to want to start a creative project together. We have seen many attempts—failed, successful and in-between—of friends starting a band, a café or a library together. The push and pull of the arts versus capitalism, individual vision versus collective effort, systemic barriers versus cultural gaps all considered, the trio behind Karmash (2025) wants you to attempt a creative endeavour with your friends anyway.

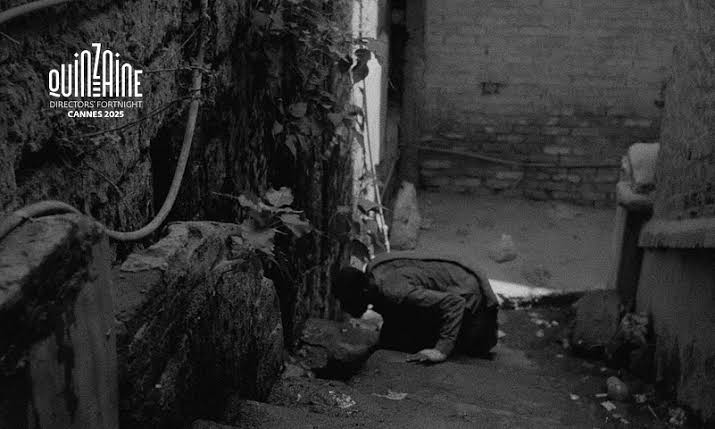

Aleem Bukhari, Shahzain Ali Detho and Irfan Noor K are part of the multi-hyphenate team behind the 15-minute short film Karmash that premiered at the 2025 Directors' Fortnight, an independent sidebar at Cannes Film Festival, back in May. The film revolves around an unnamed narrator who is the last standing man of his near-extinct tribe. Shot in black and white, the film takes us through one man’s account of his life and memories, weaving in what he calls his ancestral tradition. Karmash follows a similar vein as their previous 40-minute experimental short, Anaari Science (2024)—not in story or themes, but in the exploration of the absurd in the mundane.

Among the three of them, Noor K (who is from Gwadar, Balochistan) is the only one with formal higher education. Bukhari and Detho, on the other hand, are both film school dropouts from Hyderabad. The group of misfits, as they like to self-identify, insist upon a rigorous passion for filmmaking, and by extension, art in general. I sat down with the trio to talk about craft, films, influences and the frustrations of trying to create art in Pakistan.

This conversation has been edited and shortened for length and clarity.

Fizza Ghanchi (FG): Aleem, let’s start with your creative process. How do you begin writing the script, considering you are the one who will be directing it later? Do you find writing and directing your own projects easier?

Aleem Bukhari (AB): Yes, it's definitely easier. The visual style and thematic concerns are inherent to our writing process, especially because we know we are the ones who’re going to translate the work into its final visual format.

This parallel creative work is essential. The way a novelist or a short story writer tells a story is, in a way, more direct, even visually. As a screenwriter, though, you have to go beyond just the visuals and focus on the sound, the movement. There are questions that are always running in our minds: what will we see first? And then what? And then? So on and so forth. It’s a very formulated thing. How we are going to direct a scene remains in our mind when we are writing.

Cinema is not only a narrative story, it's an audio-visual one. You need to think in images and sound. Being a writer who understands film, then, is beneficial.

FG: David Lynch once called movies “moving paintings but with sounds”, which explains what informs or maybe inspires a lot of his aesthetic and creative choices as a filmmaker, especially as someone with a background in painting. Do you have similar thoughts about directing or cinematography? Or do you have an alternate approach?

AB: I’d say I have a similar approach—painting was a huge influence on me as well. I used to create illustrations before I knew how to make films. When I would watch something like Tarkovsky, for example Stalker (1979) or The Mirror (1975), I’d paint or illustrate inspired scenes afterwards.

My paintings and illustrations would take on a life of their own. I’d look at a painting of mine and wonder: what if it becomes real? What if it moves? What if it goes beyond the still image? That, eventually, led me to film. That's why I also made animations early on; because I agree with David Lynch about taking painting further. You want to make it more lifelike with sound and movement. It’s a feeling that you want to capture. I think painting has been a huge influence on cinematography for me—on my understanding of style, composition and framing.

Guerrilla filmmaking is the actual new wave, where younger people are working without any major studio sponsorship. When more people start working with this mindset, which is how we made our films, which is a French new wave type attitude, then an actual new wave will come.

FG: Shahzain and Irfan, how about you? Whom do you credit as your influences—filmmakers or otherwise?

Shahzain Ali Detho: There are quite a few filmmakers whose work I feel connected to on a personal level, but some of the main ones I can name are Nuri Bilge, Michael Haneke, Edward Yang and Anurag Kashyap.

Music has also been a great influence on my work, inspiring my writing as well. Massive Attack, Pink Floyd and Rage Against the Machine are just some that come to mind immediately. I am fond of the old school, grunge metal bands who rebelled against the norms through their music—Nirvana, Guns N’ Roses and the likes.

Irfan Noor K (INK): I'm a bit different than Shahzain and Aleem when it comes to my filmmaking journey or how well-versed I am in my own craft. I’m more of a “feelings” kind of guy. To be very honest, I've been working on trying to make a filmmaker out of myself since 2014. Aleem has probably been the biggest influence on me in this regard. He has shaped my ideologies and the way I approach a creative project. The reason is that my ideas are always grand and I find it hard to bring them down, to ground them in reality. Aleem continues to remind me to personalise my ideas, make them authentically me and focus on the small things.

Now, whenever I do something, it has to speak for me, for my culture, for my people, for my history—this has become a guiding principle. I created The Land of My Forefathers (2021)* with this intention.

Film, for me, is a medium of preservation in a way—a time, a place, a culture, an idea—and I'm trying to preserve my culture and history in a digital form, so that it will remain somewhere, even after I'm gone.

FG: A lot of our popular culture is absurdist, in my opinion, with prominent characters rooted in speculative fiction, such as the Ainak Wala Jinn. I find Master Jalal in Anaari Science (2024) falls in a similar category. What was the inspiration behind him? Any pop-culture references?

AB: This is a complex question. While there’s no direct influence for the character, per se, naturally a lot of experiences and encounters we have had growing up helped us shape him. Everyone has seen teachers in school who don’t talk much, they’re often rude. You see them from the eyes of a child and often wonder what this sort of adult would be doing in different scenarios? What do they do at home, for instance?

Storytelling allows you to dive into the lives of such people. Often they don’t exist, because they’re an amalgamation of so many influences, but you want them to exist. And, you want to know how they exist. What do they do at home? Are they into the occult? All sorts of questions come up. Most importantly, what if you are forced to witness them? That allows you to craft the feeling that the audience will have. So, I suppose the influence for him comes from all around us, and all the lives we have lived so far, together and individually.

Karmash was a different experience altogether. It was wilder and liberating. I was there with Aleem from the inception and even told him to not involve anyone else. I told him to write something and we will shoot it over a weekend. Just the two of us!

FG: Irfan I have seen your acting in previous projects with Aleem such as in Sapola (2018) and Anaari Science (2024); now you’re in Karmash. How has this journey been for you?

INK: Sapola seems so long ago! I still don’t know if I did a good job there or not; the character felt restrictive. But, I was younger and naive, and still learning the ropes.

Master Jalal, however, was as interesting for me to play as he was for you to watch. He was quite restrained and restrictive as well. With him, it was more about what not to do, rather than what to do, which is hard to do. I had to focus more on what Aleem wanted out of the character, as opposed to what I felt like doing with him, due to the demanding nature of the script.

Karmash was a different experience altogether. It was wilder and liberating. I was there with Aleem from the inception and even told him to not involve anyone else. I told him to write something and we will shoot it over a weekend. Just the two of us! Then the idea got bigger and we had to bring everyone else in the team to execute it.

The character, though, was rich in emotion, history, feeling, yet I did not feel restricted at all. It was more expressive, free, physical. It's heartbreaking what Karmash’s character goes through, but I felt very connected to him; he felt more like me than any of the others, if that makes any sense.

FG: How was the experience with filmmakers at Cannes and how was it different from the filmmaking community in Pakistan?

AB: The most notable thing for me personally was a lack of arrogance surrounding who they were or what they had accomplished. I don't think I've seen that in Pakistani filmmakers. The filmmakers we met there were just as excited about being selected for the festival as we were. They didn't have any airs about them. All of them were humble and down to earth; their only concern was making films. Their excitement to discuss new ideas and projects was infectious and it was heartening to see their genuine interest in our film. It was a great experience throughout and I find it sad that it’s not always the same case here.

FG: How was the film received at Cannes?

AB: I think, with all honesty, the filmmakers really enjoyed the film and so did the crowd. Some people came to us later on after the screening to talk about Karmash in detail. Karmash is not the sort of film that elicits unanimous or overwhelming acclaim from a crowd and we didn’t expect that either. It is a unique, genre film, weird even for a place like Cannes. Documentaries and a certain type of film are celebrated a lot internationally as opposed to more personal stories coming from Pakistan or the wider South Asian region. The stories that get too personal or weird don’t get celebrated that much, which is unfortunate. I don't know why but this is how it is. Therefore, the response we did get was encouraging and more than we expected.

FG: At the Crescent Collective panel that took place at Cannes, the idea of a ‘new wave’ was brought up. What are your thoughts on this ‘new wave’ and where do you think it stands with the current state of Pakistani cinema?

AB: Firstly, I think it’s important we define what we mean by new wave. Any time something different comes out, people are quick to label it the ‘new wave’. We saw that with Joyland (2022) and with many of Shoaib Mansoor’s films, and all those that came in between. I don't agree with this type of definition.

If we look at new wave movements from around the world—the Taiwanese or the French, for instance—they were defined by young people creating outside (or even against) the system. They invented their own methodologies; even American New Wave was a response against the Hollywood studio system.

Here, unfortunately due to a variety of factors, many young people are conformists—they seek approval and then make films, as opposed to standing against the system. Instead of creating their own modes of operation, their own methodologies they fall into the system. They want to create the way they’ve been directed to. From technical elements to even the stories they tell.

Young creatives are inspired by what they see being done elsewhere and want the exact same thing. They, for example, want to have the lighting which they see in Coke Studio videos or in Coke ads. This system and commercial-driven attitude which young people adopt need to change before any ‘new wave’ can happen. They need to create what they want to, rather than replicate what they’ve been seeing on TV.

Guerrilla filmmaking is the actual new wave, where younger people are working without any major studio sponsorship. When more people start working with this mindset, which is how we made our films, which is a French new wave type attitude, then an actual new wave will come.

* The Land of My Forefathers will be available for the public on YouTube, starting 11th August, 2025.