It was the peak of the summer season in Pakistan’s picturesque Gilgit-Baltistan last year. The roads were unusually busy, packed with an assortment of four-wheel drives, sedans, and Willys jeeps — all moving in a careful rhythm. That is, until a white Toyota Corolla with a number plate from outside GB suddenly overtook a jeep, recklessly speeding on the narrow mountain road. “These visitors from Punjab… they don’t know how to drive in the mountains, and risk everyone’s lives,” muttered a driver who hails from Skardu and runs a car rental service for tourists.

At the start of this summer season, on May 16, tragedy struck when a vehicle carrying four young tourists from Gujrat, Punjab, plunged into a gorge along the main highway. Their bodies were recovered a week later from the banks of River Indus near Skardu.

Issuing a timely warning, the Gilgit-Baltistan’s Department of Tourism and Culture reminded commuters in a notice that the region’s roads demand more than just basic driving skills — they require the expertise and calm of a seasoned driver who understands mountain terrain “like the back of their hand.”

Further, to better regulate tourism and generate revenue for sustainable development, the GB government has also introduced new fees: tourist vehicles will now be charged Rs 2,000, while motorcycles will be required to pay Rs 500, according to a recent notification.

Gilgit-Baltistan welcomes hordes of visitors every year — thanks to improved access via an expanding road network, more frequent flights, and an eased visa process for foreign tourists. But this growing influx comes at a cost: the surge brings not only human and vehicular traffic jams — some tragically ending in accidents — but also environmental degradation caused by regulated construction, diesel fumes from generators during frequent power outages, and littered landscapes strewn with plastic bottles and food wrappers. The region’s cultural heritage and community well-being are also under strain.

“GB is quietly being stolen from its people, and they don’t seem to care. They are making money and are happy with it,” says Neknaam Karim, who runs Adventure Tours Pakistan, a tour company based in GB.

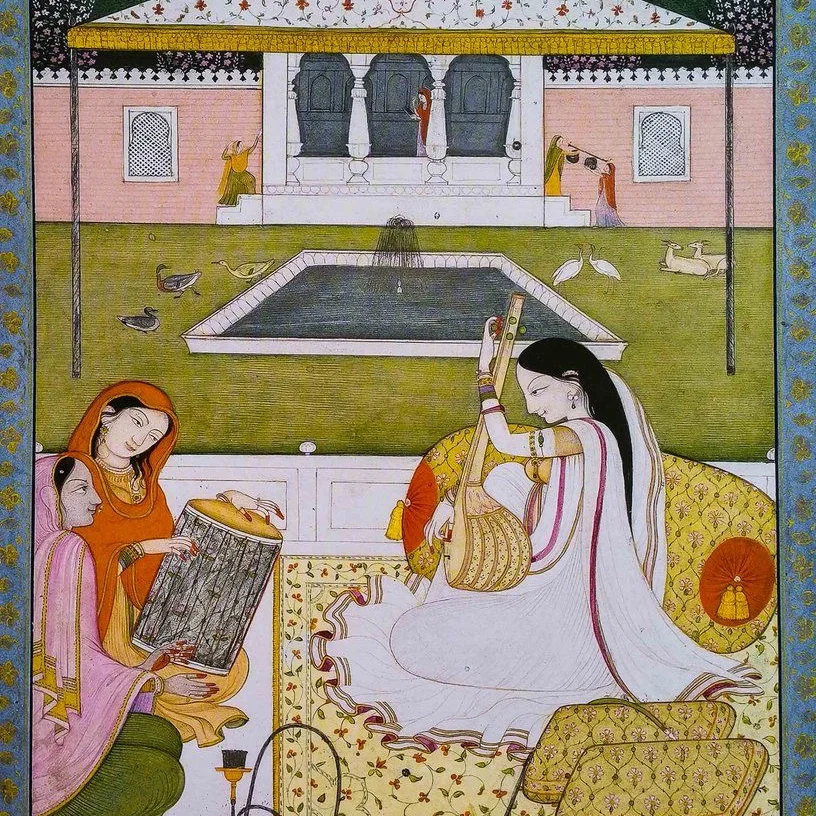

According to Iman Habib, an anthropologist, who wrote her masters’ thesis on the shrine of Baba Ghundi in Chapursan Valley, GB, back in the 1990s, visitors to this region were mainly “conscious consumers”—researchers, scholars, trekkers, and conservationists. “I remember meeting snow leopard enthusiasts from Nepal, Bhutan, and Germany. There was then an unspoken code of respect and recognition—that they were in an old, politically fragile ecosystem with cultural heritage.”

Decades on, however, the traditional, indigenous way of life that defines much of GB’s socio-cultural fabric is coming into contact with modern ideas and habits, largely brought in by today’s urban visitors. These new tourists, she says, are “without much mindfulness for its local, indigenous communities and their ways.”

***

Gilgit-Baltistan boasts some of the most breathtaking landscapes on the earth. It is home to nine national parks, including the Nanga Parbat National Park and the Central Karakoram National Park — both of which cradle five of the world’s 14 eight-thousanders. These parks are a slice of heaven: snow-capped peaks pierce the sky, gushing rivers cut through deep valleys, and lush meadows, laced with winding streams, inhabited by ibex, markhor and other wildlife. The quiet rhythm of shepherds tending to their grazing cattle adds a human touch to the vast, untamed wilderness, where, one imagines, fairies might dance and sing.

It’s no surprise, then, that the wonder and magic of GB lure thousands of tourists each year. According to official data from the Gilgit-Baltistan Tourism Department, 20,490 foreign tourists visited the region in 2024 — an increase from 16,130 in 2023. About 46 percent of all foreign travellers to Pakistan make their way to GB.

In 2024, approximately 989,793 domestic tourists visited GB. Among the local tourists, Skardu topped the list of the must-visit places, attracting 30 percent of the visitors, followed by Hunza with 27 percent, and Gilgit with 13 percent.

The influx includes both leisure travellers — often found in hotels in Skardu, Shigar, Hunza or Gilgit— and adventurers seeking solitude in remote valleys, camping under open skies.

…[Locals] are wary of lessons from other spoilt spots in the country, like Naran, Kaghan and Murree, where tourism has become so toxic that it has changed the ecology and culture of the place

This year, tour operators had anticipated a further surge in visitors, especially after CNN listed GB among the top 25 places to visit in 2025. However, the recent escalation in tensions between Pakistan and India has led many foreign tourists to cancel their travel plans. “Last year, I managed 600 clients," says Neknaam Karim. “This year, I have confirmation from fewer than 300. Many of them cancelled after the situation between Pakistan and India worsened.”

Still, Karim remains hopeful that local tourism will pick up this summer, now that schools are closed for the summer holidays. It’s always difficult to predict local tourism trends, he adds, “because domestic travellers tend to make last-minute travel plans, unlike foreigners that book months in advance.”

***

One wonders if sustainable, community-led tourism is even part of the conversation among people who call GB their home, and if they are wary of lessons from other spoilt spots in the country, like Naran, Kaghan and Murree, where tourism has become so toxic that it has changed the ecology and culture of the place.

Karim says his clients often complain about heaps of garbage piling up in open areas and along roadsides. “It especially unsettles foreign tourists,” he explains, “since the GB government charges $160 for waste management — on top of a $150 permit fee and a $30 parking fee — for entry into Khunjerab and Central Karakoram National Parks. Yet, waste disposal remains poor, particularly in the Baltoro region, which is among the worst affected.”

Overtourism is pushing GB toward rapid modernisation. The swift rise of concrete structures of hotels, markets, and restaurants is a particularly worrying trend. Those aware of the area’s traditional architecture note that although by-laws exist, enforcement is weak. They explain that traditional architecture is being sidelined, as materials like steel and concrete offer quicker results. Wood, which once defined local design, takes nearly a year to season, and so is often skipped for convenience.

***

Locals, perhaps desperate to seize the moment, are rushing to adapt to meet the needs and tastes of the tourists. “The McDonaldisation of society,” says Iman Habib, is evident as burger joints have sprung up, selling plastic-encased fast food made with low-quality, pre-packaged ingredients. There are some notable local alternatives such as the locally run Yak Grill, which blends traditional ingredients—like yak meat and fresh butter—into a global favourite, the Big Mac-style burger.

Similarly, she notes how the Yasin Valley’s traditional power food kilao — originally made by stringing walnuts on a thread and dipping them in fresh mulberry syrup — now has urbanised variants such as chocolate-dipped walnuts.

Still, some unique safe spaces persist, away from the glare of urban tourists. “For example, the Khanabadosh Baithak in Ghulkin offers a refuge for many queer and progressive groups who feel suffocated in their urban cliques.”

There is much to observe and analyse in GB’s case: how can cultural identity and indigenous roots coexist with development and modernity? For now, there is good reason to feel uneasy about the ongoing shift — the changing character and monetisation of this unique landscape. One can only hope that the next wave of tourists arriving in GB is conscious of this ancient ecosystem, and can respect it.