What set this year’s Indus Conclave apart from other cultural conferences and literary festivals of its kind was how well its focus on bringing together perspectives from across the Global South represented the zeitgeist of today’s engaged youth and citizenry. The atmosphere was visibly charged, almost catalysing a break from conventional narratives and ways of thinking. Rich and nuanced individual sessions from Articulating Climate Justice from the Global South to Rereading Western Classics (from a postcolonial lens) invited participants to revisit traditional world views and constructs and seek out a new way forward.

Against the backdrop of Gen Z protests in Bangladesh, Nepal and Indonesia against the corruption, greed, and ineptitude of establishment governments, and the unmasking of the double-standards and hypocrisy of Western governments and their regional vassals, the Indus Conclave offered a platform not only for the articulation of genuinely fresh ideas, but for the development of productive cross-linkages and collaborative efforts between the academics, journalists, thinkers and practitioners of the Global South.

It was in line with this spirit that the Roundtable Discussion on Pakistan’s Growth Trap sought to bring together diverse perspectives from a panel of experts at the very top of their respective fields, spanning not just business and economics, but also education, climate change, culture, governance and urban development.

There is no shortage of analyses on Pakistan’s economic challenges; the op-ed pages of Pakistan’s English broadsheets are filled with familiar lamentations around fiscal constraints and the need for ‘structural reforms’, which will somehow set the country on the path to growth. Perhaps one of the reasons the discourse around Pakistan’s economy has become so banal is that much of what is said is not only purely from an economics and business policy vantage point, but it is all underpinned by a set of common assumptions.

The most interesting outcome from the roundtable discussion was actually the emerging consensus that not only is growth not intrinsically good for Pakistan, but that the country may actually be better off not pursuing purely economic growth at all.

At the outset, the roundtable panellists challenged the underlying assumptions. Governance expert Sakib Sherani set the stage for the direction of the discussion, arguing that pursuing growth is a policy choice. Cuba and Iran, he explained, have not pursued growth, but rather development, with the ultimate aim being to make human lives worth living. This was the original framing of the concept of growth as something that is intrinsically good because it leads to more development, but somewhere along the lines, the goal itself became growth. As Dr Faisal Bari humorously illustrated, when you ask someone how they are doing, you expect them to talk about their life, not their financial performance.

Worker productivity, and by extension, growth, are predicated on a strong educational foundation and good health, explained Dr. Bari, and this is where our priorities should lie. Hina Shaikh, the senior country economist for Pakistan at the International Growth Centre, went a step further, arguing that we may in fact be investing in the wrong types of growth. Inclusivity is an afterthought for policy makers, she said, whereas given how large a share of our population comprises women, young individuals and informal workers, we need to organise our systems around enabling them. Only then can we harness the country’s full productive potential.

Where and how resources are allocated invariably ends up influencing the kind of work people do, how they live and how society as a whole thinks and behaves. Will the avenues for leisure primarily be shopping malls and restaurants or art galleries and theatre? The flow of investments in Pakistan is towards real estate and subsidies to state owned corporations that are not only unproductive, but actively causing environmental degradation and harming the population at large.

Dr Fizzah Sajjad, an expert in urban development, questioned the narrative espoused by many among the global economic elite, that growth will lead to greater inclusivity and sustainability. To the contrary, she explained, evidence points to growth being accompanied by increasing inequality and poorer quality of life for workers. Great Britain during the late 1800s saw a dramatic increase in people living in squalor and suffering adverse health effects from ongoing industrialisation. Pakistan today similarly suffers from increased use of low quality fuels, with incapacitating smog enveloping major cities every winter. The short term deleterious effects on individual health and productivity are self-evident. The long term adverse impact from air pollution has yet to be quantified.

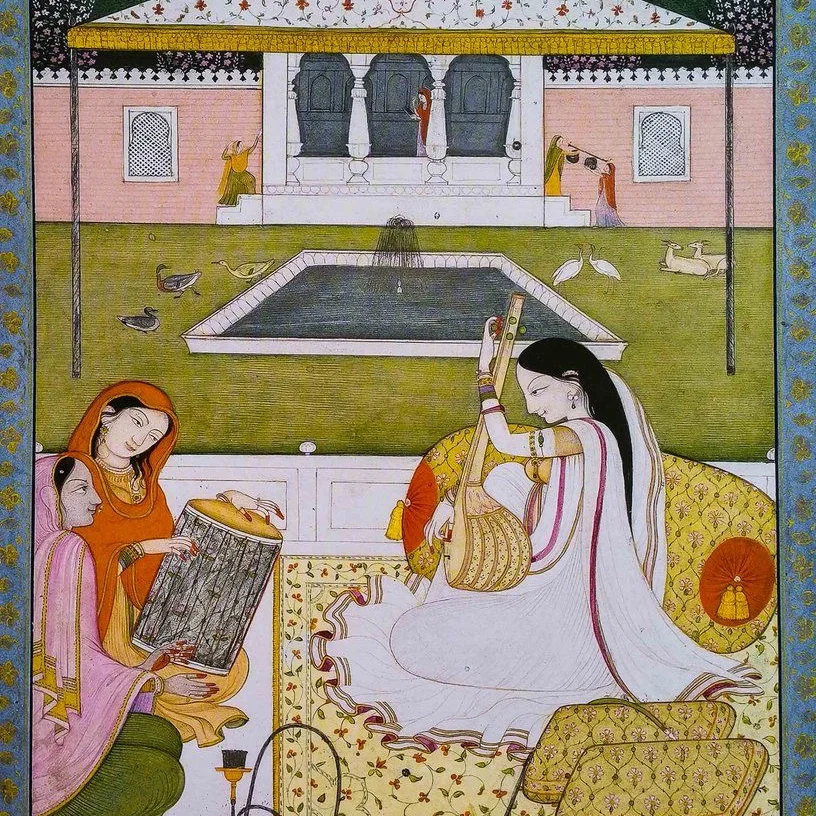

Where and how resources are allocated invariably ends up influencing the kind of work people do, how they live and how society as a whole thinks and behaves. Will the avenues for leisure primarily be shopping malls and restaurants or art galleries and theatre?

Perhaps the most interesting outcome from the roundtable discussion was actually the emerging consensus that not only is growth not intrinsically good for Pakistan, but that the country may actually be better off not pursuing purely economic growth at all.

What are specific, actionable measures that we can take today to get the right kind of growth — in educational outcomes, healthcare outcomes and quality of life outcomes? More than any other question asked during the nearly three-hour discussion, it was this one that the panellists, arguably among the best-informed and most rigorous thinkers in the country, struggled with most. A transformational reform of the overall system of governance or a series of small incremental changes gradually making headway in the right direction? The jury is still out.