Modest fashion is a slippery term—what’s considered modest in Karachi is different from Jakarta, and Tehran has its own entirely different playbook. It’s an aesthetic governed by cultural codes, religious interpretations, and personal style, making it a fascinating, ever-evolving space within the global fashion industry. Yet, while modest fashion has taken off in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, Pakistan’s relationship with it remains complicated.

At home, the conversation around modest fashion is often marked by an odd paradox. Is it even modest to do fashion? And vice versa. Many Pakistani brands that market themselves as "modest" opt to exclude women from their visuals altogether—cropping out faces, posting faceless mannequins, or simply showcasing their clothing on hangers. It’s an erasure rather than an articulation of modesty. The defining rules? No cutouts/holes, no deep necklines, and, in some cases, no prints or embroideries featuring animals—birds, elephants, and even butterflies are omitted under certain interpretations. But beyond these restrictions, no major Pakistani brand has carved out a niche purely for modest fashion. Instead, most brands play it safe, attempting to appease both ends of the market without making a distinct statement.

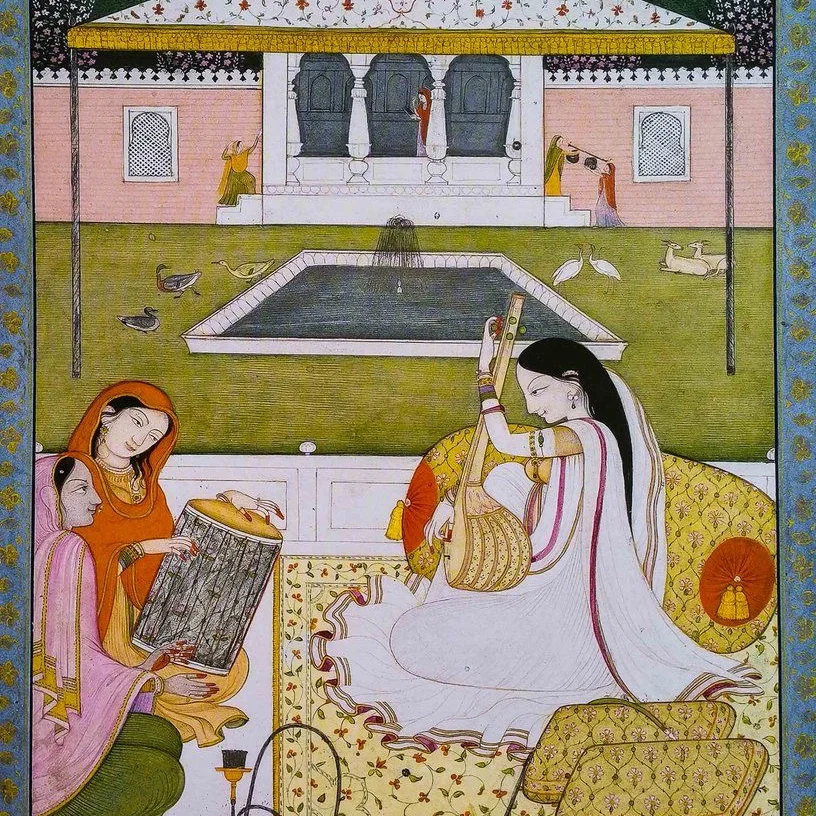

The irony is that Pakistan is a country where a significant portion of women already wear modest clothing. Unlike the Middle East, where abayas dominate, or Indonesia, where a certain type of cultural clothing forms a thriving industry, Pakistani women navigate an incredibly diverse landscape of traditional attire. The everyday shalwar kameez, dupatta, and long tunics inherently fall into the category of modest wear, yet they’re rarely marketed as such. With unstitched fabric and tailors available on nearly every corner, women have complete control over how modest or “revealing” their clothing is—so who is modest fashion really for in Pakistan?

Unlike the UAE or Iran, where coverings are enforced by the government, Pakistan lacks a dominant, society-wide standard of covering. Women from different faith sects and communities interpret modesty in their own way. The Bohra Muslim community, for instance, has a rich tradition of customizing their ridas—a type of modest dress that allows for self-expression through fabric, pattern, color and embellishment. To my limited knowledge, no other community has such play for creativity, yet every group does their own thing. Despite this diversity, no major Pakistani designer has ventured into abayas or coverings beyond the occasional Eid capsule, with the exception of Sania Maskatiya and Sapphire. While Middle Eastern luxury brands have transformed the abaya into a high-fashion statement, most of the Pakistani labels remain hesitant, perhaps unsure of the market’s appetite for such dedicated offerings.

Hena Anwar, the designer behind Wov the Brand, offers a nuanced perspective on modest fashion, viewing it as a form of personal expression rather than a rigid framework. She believes modesty isn’t just about covering up but about creating clothing that feels authentic to the wearer. Anwar also challenges the notion that modest fashion needs to be confined to a particular look: “A starched cotton button-down paired with trousers is effortlessly chic and could be considered modest, depending on how it’s styled. Why pigeonhole the concept when it can be so expansive?” She points out that the global perception of modesty is evolving, and Pakistani designers have a unique opportunity to shape that narrative. “There’s this outdated idea that modesty and being fashion-forward are at odds, but they can beautifully complement each other. Pieces like blazers, flared pants, or long skirts hold their own anywhere in the world — modesty doesn’t make you any less stylish.” With a presence in two of Karachi’s biggest malls, Wov the Brand reflects a growing demand for thoughtfully designed modest wear.

Pakistani fashion is seeing a growing divide. One segment embraces internationally inspired trends, experimenting with bold cuts and modern silhouettes. Meanwhile, another segment is pushing back, criticizing what they see as Western or Bollywood influences creeping into Eastern wear. The media platform Propaganda recently highlighted this frustration, with women voicing concerns over sheer fabrics, plunging necklines, sleeveless designs, and increasingly revealing cuts in local brand campaigns. This divide reflects a broader cultural shift, signaling the need for brands to navigate both needs sensitively.

Despite the lack of dedicated modest offerings by fashion brands in Pakistan, there is a strong demand for clothing that adheres to varying definitions of modesty. The absence of structured offerings has led women to rely on customization and smaller boutique designers to meet their needs. In contrast, countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Indonesia have flourishing industries specifically catering to modest fashion, with dedicated stores, fashion weeks, and international collaborations. Pakistan, with its rich textile industry, has the potential to tap into this market, but so far, few have taken the plunge.

Unlike in the Middle East or Indonesia, where modest fashion bloggers thrive, Pakistan’s social media space still leans toward Western-style or traditional desi fashion without the "modest" label.

One model who has embraced modest fashion in recent years is Farwa Kazmi. With over a decade of experience in Pakistan’s fashion industry, she was one of the first covered models to appear in a Garnier Pakistan ad. For her, modest fashion is more than just clothing — it’s about staying true to her values while embracing style. “Representation matters,” she says. “Seeing real models in modest fashion makes it more relatable and aspirational. Many women hesitate to embrace modesty because they feel elegance can only be expressed in less covered clothing. But modesty and fashion aren’t mutually exclusive — you can be stylish, confident, and elegant while dressing modestly.”

Meanwhile, we have Sheikha Mozah of Qatar who is a masterclass in how one can embrace the high fashion trends while maintaining a regal, covered-up look. Elsewhere in the world, however, there are few in this domain. The most prominent veiled Pakistani public figure in recent times remains Bushra Bibi, the wife of former Prime Minister ex-cricketer Imran Khan, though she is certainly not an influencer in the fashion sense.

In recent years, European brands have recognized the potential of modest fashion. Retail giants like H&M and designer brands like Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana have launched modest fashion collections, targeting a growing market of primarily affluent Arabs. The question is: why hasn't Pakistan, with its deeply ingrained culture of modest dressing, fully embraced this industry? Part of the reason may be the lack of a singular identity or focus. In countries like Indonesia and the UAE, modest fashion has clear-cut boundaries of culture and beliefs and is often reinforced by societal norms. In Pakistan, the interpretation of modest dressing is more fluid as the population is very diverse, making it harder to market products as a distinct category.

Perhaps the biggest question is whether modest fashion even needs to be a separate category in Pakistan. Given that a vast majority of women already wear long tunics, full sleeves, and dupattas, is modest fashion just a repackaging of what already exists? High-street brands like Khaadi, Ethnic, Generation, Alkaram and Gul Ahmed have endless options that align with modesty, even if they don’t explicitly market them that way. And with unstitched fabric reigning supreme, customization is the real power—any outfit can be made more or less modest depending on personal preference.

Hareem Zahid, Founder and Creative Head of ABAA, a 13-year-old modest fashion label, emphasizes that true modest fashion goes beyond aesthetics — it requires adhering to Shariah principles in design, marketing, and styling. “Creativity thrives without boundaries, but modest fashion demands careful restraint. The challenge lies in balancing innovation with the principles that define it.”

She also points out that Pakistani designers often follow global trends, overlooking the country’s rich design heritage. “We have so much to offer the global modest fashion market. Instead of chasing trends, we should embrace our strengths and create original pieces that honor modesty and cultural identity.”

Having said that, we need to have a dedicated category. Because there is disdain about fashion shown in Pakistan, it is only for those with Western sensibilities. Awards shows, trade shows, fashion weeks and even brands all need to brand modest as a separate category, develop it, and promote it as such. This will certainly get better dividends.

The real challenge for brands looking to carve a space in the international market is identity. What kind of woman are they speaking to? The ones who prefer faceless mannequins and erased identities, or the ones who want fashion-forward, covered dressing that embraces visibility? The global market has already answered—modest fashion is a thriving industry in the Middle East, Indonesia, and beyond. Pakistan, however, is still figuring it out. And until a brand truly owns the space with a clear perspective, modest fashion here will remain more of an abstract standard than a defined movement.