A few months ago, Bollywood darling Alia Bhatt showed up in an Ajrak-print sari, designed by Abu Jani Sandeep Khosla. It was splashed across every South Asian fashion page, with captions invariably reading: “Ajrak, the ancient textile from Kutch”. That was it. No mention of Sindh. No footnote that this centuries-old resist-dyed cloth is just as deeply rooted across the border in Pakistan, as it is in India.

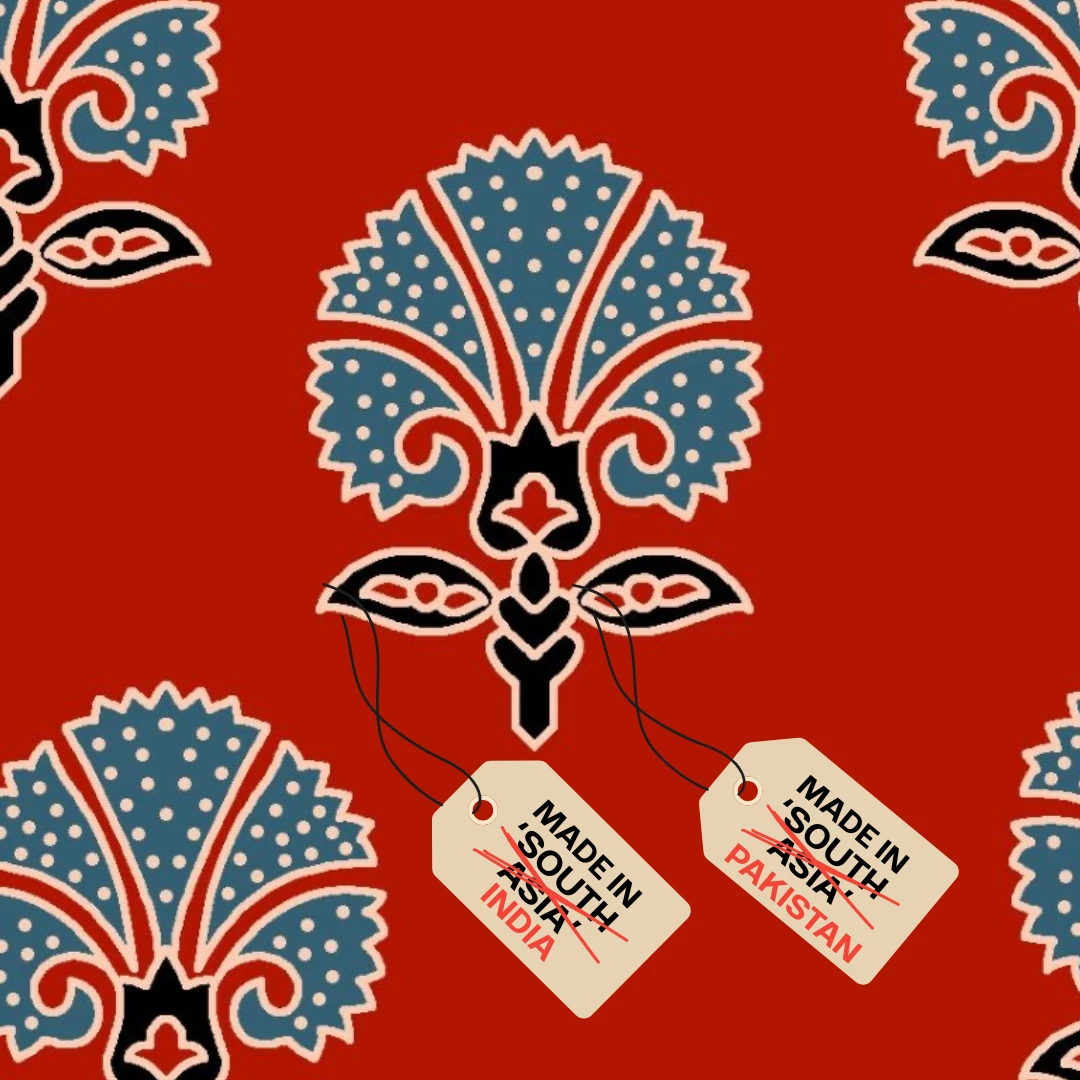

It’s the sort of thing that keeps happening. In the race to package and promote South Asian fashion to the world, India is sprinting ahead often, with items that have roots on both sides of the border. Ajrak is one of them. So is Phulkari, the floral silk floss embroidery famously worn by Punjabi and Hazara women; Chunri, the tie-dye technique that’s gone from once staple to mehendi must-have is another such item. These crafts were never confined by the Radcliffe Line, but their identity politics now are.

When Vogue UK published Osmaan Ahmed’s article “Fashion As We Know It Wouldn’t Exist Without South Asian Style”, the response was swift and telling. Diaspora creatives applauded it, grateful that someone finally said it. But when the piece was shared on Instagram, the applause was joined by a quieter tension. Several noted what the article had skipped over: South Asia does not begin and end with India. Pakistan—with its deep craft traditions from Khes to Bandhani to Ajrak—barely made it into the frame. The erasure wasn’t hostile, but rather just habitual. And that’s what stung. It’s not just Western brands who mislabel and misplace—sometimes the cultural gatekeeping happens closer to home.

Pakistan did not exist before 1947, so these aren’t “stolen” crafts, they’re shared legacies. But try telling that to the search algorithms, where a simple “Bandhani” query leads to page after page of Indian brands, Indian festivals, Indian designers.

Much of this push comes with Geographical Indications tags which allow a country to legally claim a product as part of its national heritage. Think of Champagne in France, for example. A GI tag protects the name and origin of the item, gives it its commercial value and boosts its chances on global platforms. India has been quietly collecting these designations for years. It is not about who did it first, rather it is about who documented and showcased it better.

As Hassan, an Ajrak artisan from Hala whose family has block-printed for generations, put it: “Ajrak has been part of Sindh for centuries; our fathers and grandfathers made it with the same wooden blocks and natural dyes. But you also find Ajrak in Kutch and Rajasthan. It is the same river of craft flowing across borders. If one country claims it through something, it feels like cutting the river in half, leaving us with no recognition for our history.”

Of course, the history is messy.

Pakistan did not exist before 1947, so these aren’t “stolen” crafts, they’re shared legacies. But try telling that to the search algorithms, where a simple “Bandhani” query leads to page after page of Indian brands, Indian festivals, Indian designers. On Instagram, “Phulkari” is now mostly associated with bridal traditions in Amritsar. The Pakistani side of Punjab, where the stitch tradition also thrived, barely registers.

That’s not to say they don’t matter or don’t deserve the attention. Indian brand Neelgar has been experimenting with Bandhani/Chunri, not just reviving it, but updating it with contemporary silhouettes and styling. Their pieces are striking, bold and nothing like the dowdy chunri dupattas people once dismissed. There’s also a growing awareness around Khes, the thick handwoven cotton spread once an essential dowry item in Punjab. While Indian initiatives like the “Khes Project” have made waves with stylised reissues of the weave, Pakistan is only just waking up to its design potential beyond nostalgia.

Yet, some things remain stubbornly locked in a time capsule. Ajrak, for instance, is still treated more like a cultural symbol than a design element in Pakistan. You’ll see it on politicians during Sindhi Cultural Day, or framed on the wall of a heritage restaurant, but rarely on the rack in fashion-forward stores. Meanwhile, Indian designers like Heena Kochhar and Raw Mango are reinventing it into jackets and separates, getting the textile noticed in Vogue and beyond.

Hassan, the artisan from Hala, was blunt about the stakes: “Every year there are fewer of us left in Hala still block-printing by hand. People buy machine-printed cloth because it is cheaper, even though it has no soul. Now if India alone gets legal rights to Ajrak, it will become harder for us to sell our work internationally. We already feel invisible—such decisions will make us disappear even faster.”

There’s also the commerce angle. GI tags aren’t just cultural, they are economic leverage. The Basmati rice dispute between India and Pakistan is a textbook example. For years, both countries have claimed the right to market their Basmati to Europe and beyond. GI tagging could determine who profits and who gets left out of the global export narrative. Mangoes, another shared obsession, have seen similar drama. So it’s no surprise textiles are the next battleground.

Amneh Shaikh-Farooqui, co-founder of concept store Polly & Other Stories, which works with hundreds of artisans, sees the problem as both internal and external: “One of our biggest weaknesses is how protective and insular we are about craft data, artisans and opportunities, as though guarding them will keep them alive. In reality, it isolates us further. If Pakistan is to claim its fair share globally, we need collaboration across borders, across institutions and across industries. The pie doesn’t shrink if we share it; in fact, it actually grows.”

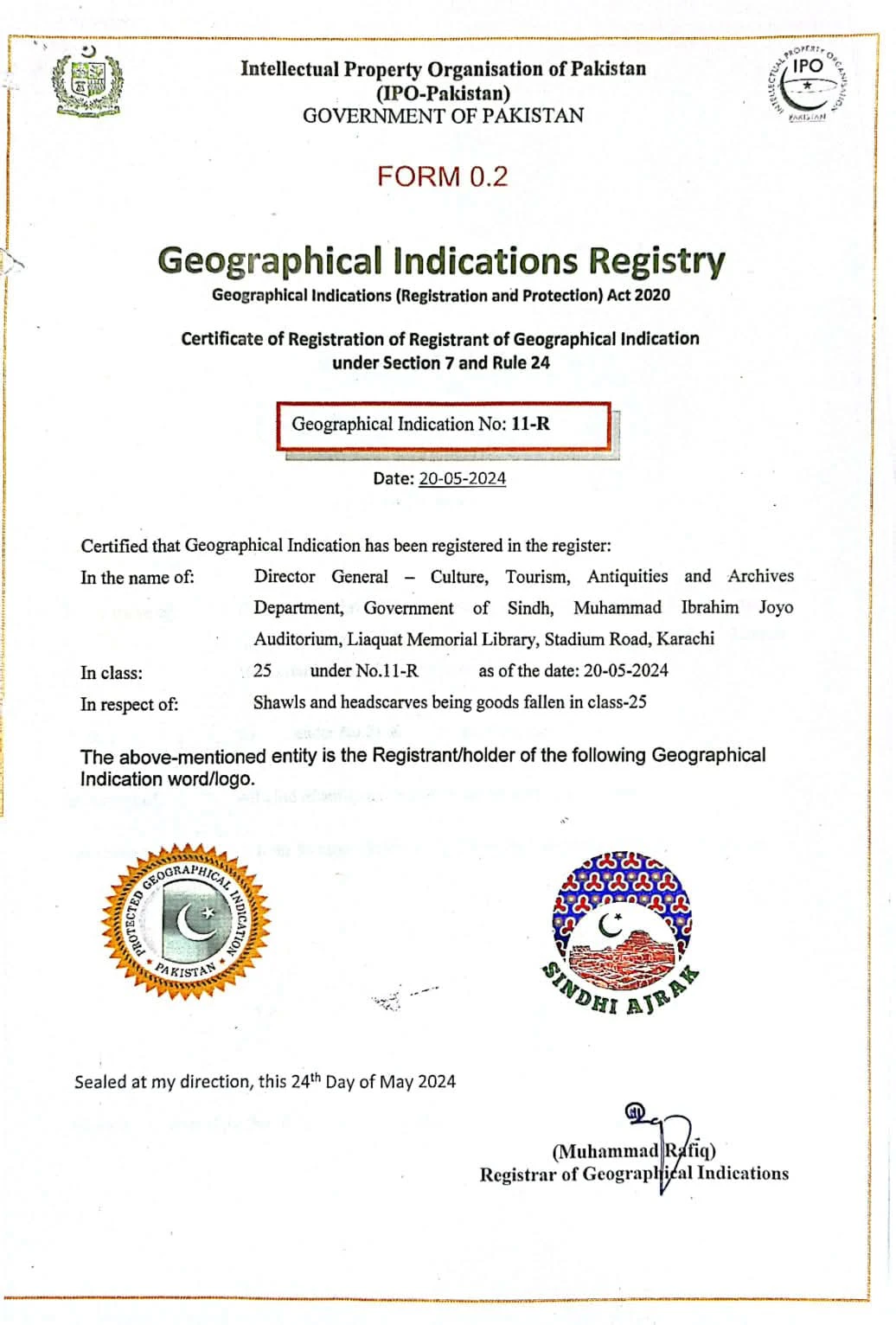

There’s truth to that. India has leveraged its GI Act since 1999 to protect Darjeeling tea, Banarasi saris, Kanjeevaram silks and more. Pakistan only passed its law in 2020, and while Ajrak has since been registered, enforcement and recognition lag far behind.

Naushaba Brohi, founder of Inaaya—a brand that once worked with Sindhi craftswomen and was stocked internationally—argues that the absence of structure has been fatal: “The real problem isn’t that India is claiming everything, it’s that Pakistan has never built the scaffolding to celebrate its own craft. We work in silos: a textile mill brand will print phulkari on a lawn jora, a designer will trot artisans down the runway, an NGO will set up a training centre in a village with no electricity. But there’s no blueprint, no consistent effort. Without respect for the artisan at home, how can we expect to be taken seriously abroad?”

The lesson is clear: it’s not just about flags and legal filings. It’s about who tells the story and how. The average foreign buyer doesn’t know the politics, they just buy what’s well-shot and well-marketed. Pakistan’s craft sector hasn’t always been great at either. Between lack of infrastructure, inconsistent branding and a chronic allergy to documentation, most of our textile traditions survive by word of mouth or worse, Instagram reposts.

Moreover, the Basmati rice fight shows how high the stakes can be. A decade-long legal battle between India and Pakistan over the fragrant long-grain rice has dragged through European courts. Initially, both sides considered filing a joint application, but the effort collapsed after the Mumbai terror attacks. India went ahead solo, while Pakistan struggled to respond. The irony? Both are the only major producers of Basmati rice in the world. Experts still say joint ownership remains the only practical solution, but politics won out over pragmatism.

The same could happen with textiles. Unless Pakistan builds strong, co-ordinated systems to claim and market its crafts, the heritage could be split both legally and commercially, very much like Basmati rice.

As Amneh put it: “India has spent decades branding its handlooms as national treasures, while we’ve treated ours as background noise. The truth is Pakistan’s crafts have equal (sometimes greater) depth. What’s missing is the confidence to position them not as derivative of India, but as distinctly ours: shaped by Sufism, by migration, by the Indus itself.”

There’s still time to shift the needle but only if we stop pretending that claiming a cultural item means draping it in nationalism and calling it a day. Fashion is business. Storytelling is strategy. And in a world where visibility equals value, you can’t afford to be shy.

The lesson is clear: it’s not just about flags and legal filings. It’s about who tells the story and how. The average foreign buyer doesn’t know the politics, they just buy what’s well-shot and well-marketed.

But there is good news. As of August 2025, The Culture Department of the Government of Sindh has successfully registered: Sindhi Ajrak, Sindhi Topi, Hyderabadi Bangles and Hala Jandi (Wooden Lacquer Work) as official cultural products of Sindh, in collaboration with the Intellectual Property Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Islamabad. However, there are many more products of Pakistan that need the government's immediate attention for registration in the international market. Products having the GI tag get better prices in the international market. Some famous products of Pakistan like Peshawari chapal, Pakol cap from KP, Majnu Khes, Blue ceramics and Chunri tie-dye can also benefit. (We attempted to reach the relevant departments for an updated comment on these specific initiatives but did not receive a reply by the time of publication.)

Will these GI tags magically fix everything? No. But maybe it’ll force the conversation out of drawing rooms and into boardrooms, eventually getting the products to Expo centres. The hope is that it will also push designers to reimagine these crafts instead of romanticising them. Maybe, just maybe, it’ll remind us, the consumers, that heritage isn’t just something you inherit, it’s something you own and fight for.