When the Vancouver-based Dhahan Prize introduced a category to honour an individual work of Shahmukhi Punjabi prose, Zubair Ahmad became its first recipient. This was for his second short story collection, Kabootar, Baneire Te Galian, in 2014. Since then, Ahmad has received this award once more with another collection of short stories in 2020, Paani Di Kundh; in 2022, an English translation of some of his stories was produced by the Canadian academic, Anne Murphy, titled Grieving for Pigeons. As a writer from Lahore, Ahmad’s body of work is greatly concerned with the city, its bygone political intensities, its comrades, its coffeehouses and cafes. But it also finds itself searching for Lahore and its people in Rome, in Vancouver, in California; in Amritsar, in Batala; in departed aunts, old friends, dreams. Like much of contemporary fiction, Ahmad’s is also sentimental, propelled by acts of retrospection. Yet there is a remarkable desperation with which his first-person ‘I’ narrators reckon with their pasts and presents, filtered through a dizzying, unpredictable stream-of-consciousness that makes Ahmad’s stories both unusually nightmarish and enchanting.

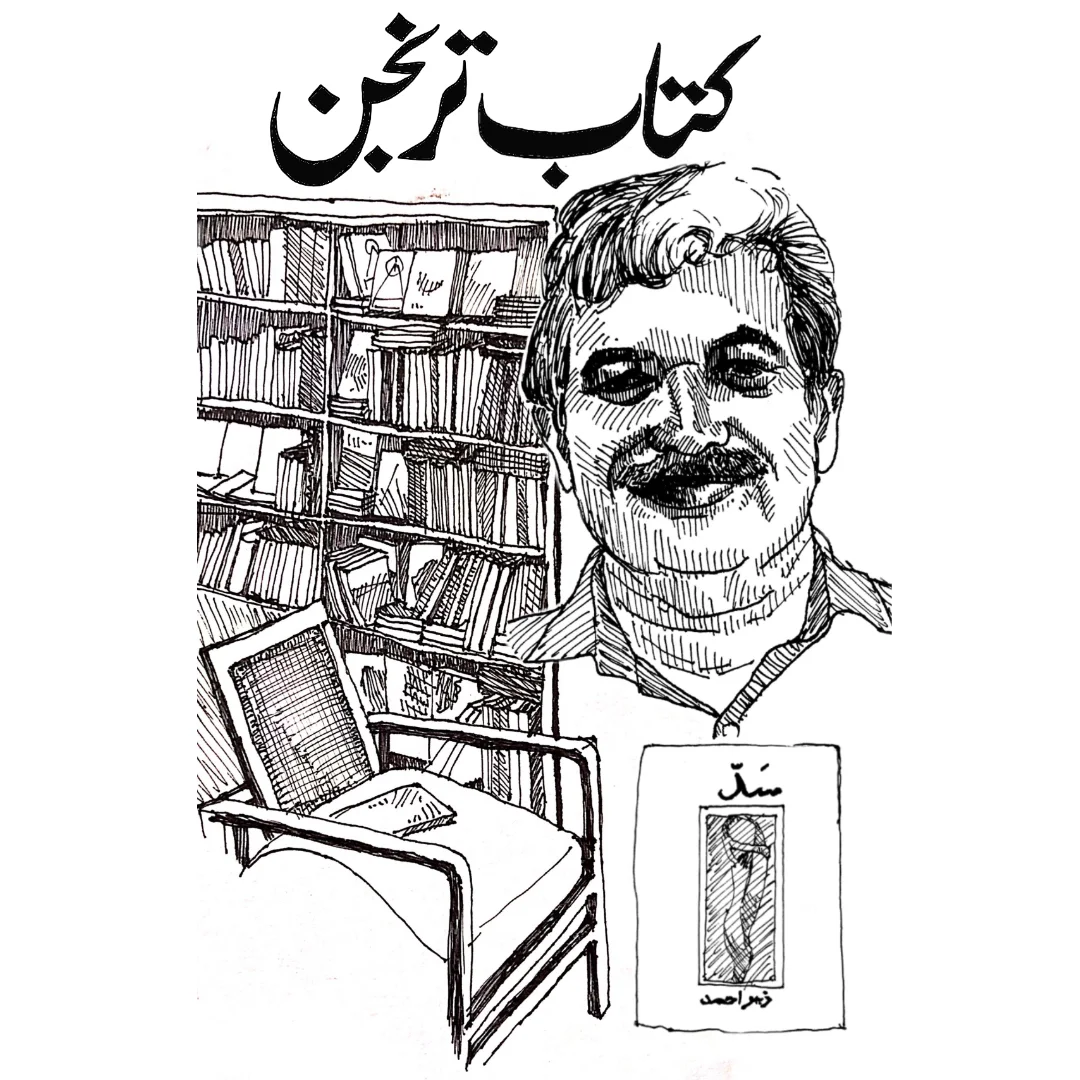

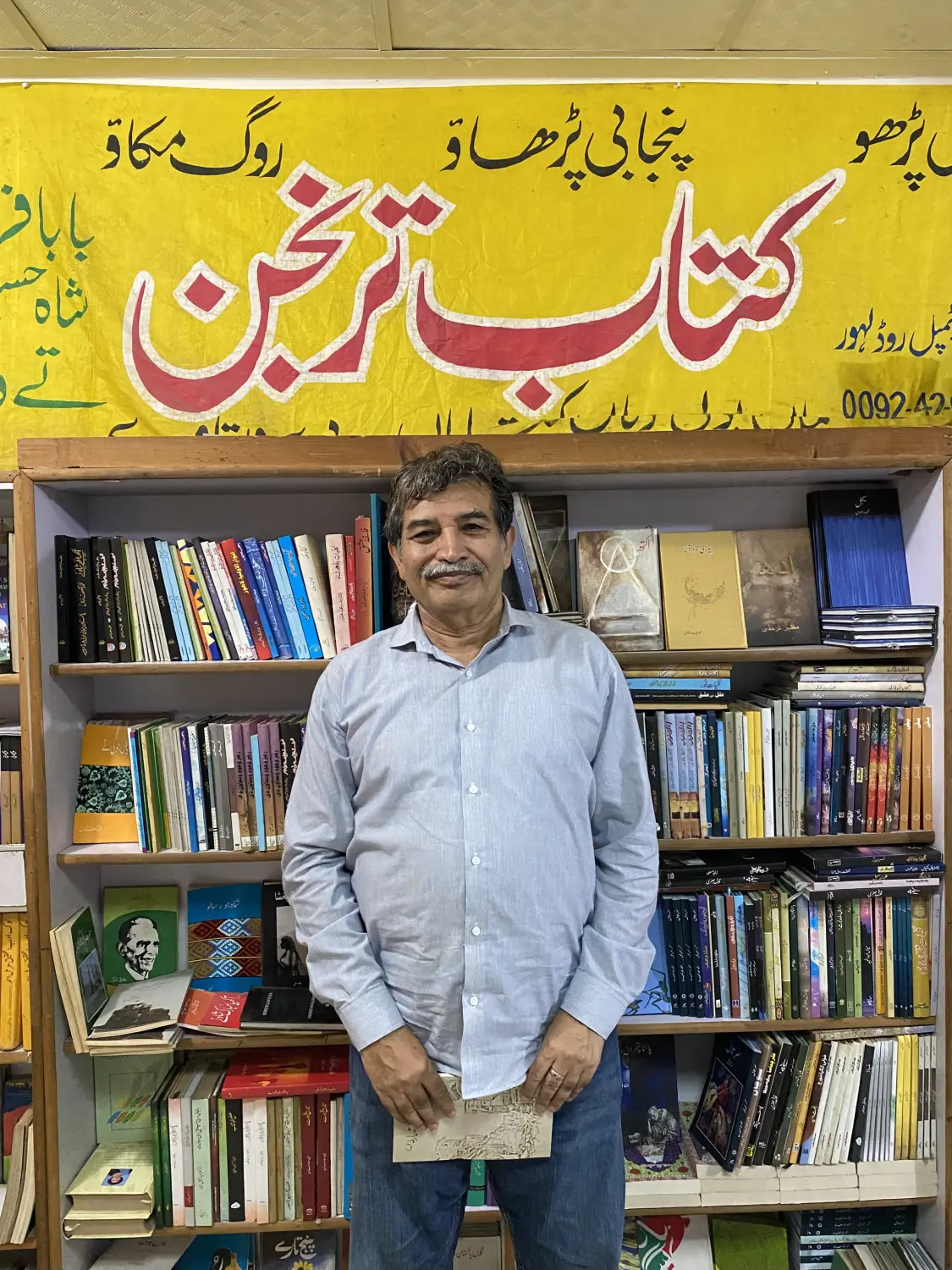

This interview was conducted at Kitab Trinjan, a Punjabi-language bookstore that Zubair Ahmad runs on Lahore’s Temple Road.

The interview has been translated into English by the interviewer; it has also been edited for length and clarity.

Rana Saadullah Khan (RSK): You were a professor of English literature for 33 years. From your stories one gleans a sense of your experiences in various foreign cities; in Ankahani, your narrator spends his boyhood summer vacation nights reading the detective novels of Ibn-e-Safi. Tell me about your childhood — how did your literary journey begin?

Zubair Ahmad (ZA): Reading and writing have been great interests since I was young. I was born in Krishan Nagar in 1958, an old neighbourhood of Lahore right behind the Secretariat. In the 1920s, Model Town was built; in the ‘30s, Krishan Nagar. It was rich — or rather, middle class — Hindus that had it built. It’s very beautiful. There are many straight streets, many old houses. It has a romance to it.

When I was there, there was an ‘anna library’ in my neighbourhood. All you had to do was give an anna and you could borrow a book for 24 hours. It’s an old culture of Lahore; the people who are my age, they must remember. Not a lot of people read back then. But I read a lot because of the anna library, especially Urdu literature by popular writers like Salma Naz, Razia Butt and Ibn-e-Safi. Even today, if you read Ibn-e-Safi, you’ll find that his Urdu is stunning. Eventually, I ended up reading more ‘serious’ writers like Krishan Chander, Manto, Qurratulain Hyder, Ismat Chughtai and Abdullah Hussein. Udaas Naslein overwhelmed me so much that there were three or four days I didn’t even come out of my house.

RSK: For a person with such wide-ranging exposure to literature as it exists in English, in Urdu, as well as other literary worlds, what was it about the poetics of Punjabi in particular that made you seek to be a writer of this language?

ZA: In ‘73, I enrolled in the Islamia College, Civil Lines for my first year. At that time, I was writing a lot of Urdu poetry; short stories too. It was the era of leftist politics; Bhutto was Prime Minister and many of his speeches and slogans exhorted students to participate in politics. But I didn’t have any ideology at the time. I wasn’t a leftist or a rightist. Eventually, I began to admire the leftists though; I liked their attitude and got attached to them.

We did so much idle roaming about back then, whiling whole nights away in restaurants. Lahore was a beautiful city in ‘73, with a population of just 1.5 million people. There was a double-decker bus that ran on Mall Road. And Mall Road looked like it belonged in Paris: so many restaurants, so many lights, always people sitting around, especially the area around Pak Tea House. Right in front of it was Peejo, then somewhat up ahead was Caffe House; further down, a restaurant called ‘Chini’ — a man called ‘Chini’ ran it — and a lot of writers, intellectuals, political activists hung around there.

There, I met Pashi, a leftist — he's passed on now — who had set up the Punjab Lok Rahs, a political theatre troupe. By then I had written about three or four hundred poems in Urdu, and had even read some of my stories at Halqa-e Arbab-e-Zauq, an Urdu reading circle. Pashi said to me, “You know, everybody’s writing in Urdu. Who will write in Punjabi? You should write in Punjabi. We have to bring about the revolution. We must do what we do in the people’s tongue.” From that moment on, I switched over. It must have been ‘74 or ’75…I was 16 or 17 years old — I matriculated at a very young age, I was really good in my studies — when I created my first ever poem in Punjabi. It’s still in my book and I’ve never looked back.

Eventually, I did my Master’s in English for practical reasons. I really loved studying literature, but it was harder to get a job with a degree in Punjabi literature, which is still the case, while with English and Urdu, you could get a job immediately. I’d done my Bachelor’s in English Literature and Psychology too. So that’s how it was.

RSK: Was it possible at that time to do an advanced degree in Punjabi literature?

ZA: Yes, Punjab University had set up a department and were offering it.

RSK: I noticed that all of the authors you’ve mentioned — Qurratulain Hyder or Abdullah Hussein for instance — are canonical Urdu writers. At the time you first dedicated yourself to Punjabi, who were some of the Punjabi writers that were interesting to you?

ZA: There were a lot of big names in Punjabi poetry and fiction: Afzal Ahsan Randhawa had written many novels, short stories, Akbar Lahori, Anwar Ali — they were all pioneers, modern. In poetry, Ahmad Rahi was alive and Najm Hosain Syed had a great reputation. There were many others besides them.

Pashi said to me, “You know, everybody’s writing in Urdu. Who will write in Punjabi? You should write in Punjabi. We have to bring about the revolution. We must do what we do in the people’s tongue.”

RSK: In your story Buss Badlaan Di Gal Kar, your narrator travels to Vancouver and is shocked by how much Punjabi literature seems to be an active interest of the citizenry. Of course, the Dhahan Prize is also awarded in Vancouver. What was your own impression of Vancouver?

ZA: People used to tell me that Vancouver is beautiful and so is the weather there, that snow doesn't fall, that it's a mini-Punjab. When I finally went to Vancouver, I really was surprised. On the stage there, I expressed that it felt like I was still in Lahore, that I had never left it. They have kept the flag of Punjabi flying high.

I met a lot of people in Vancouver, many of them writers. You know how they say: “Paindu gaya te battiyaan dekhun lag paya” (the country bumpkin went to the city and started ogling at the lights)? That was my condition. They gave me such a nice reception. I was really impressed with our diaspora, specifically the Punjabi diaspora — both the Indians and the Pakistanis are living fantastic lives over there.

RSK: Is it only in Vancouver that you’ve seen Punjabi writers from Pakistan engaging with contemporary Indian Punjabi writers?

ZA: The exchange has been happening for some time now. In the Bhutto era a lot of Sikhs used to come to Pakistan, including writers. In ‘75, if you went towards Regal in Lahore, there used to be an institution around there called Punj Darya, run by Mr Afzal. They offered a Punjabi Fazil, by which it meant that all you had to do — besides the Fazil degree — was take the exams for English, and you would have a B.A. degree. They called it doing a ‘Vaaya Bathanda’ (via a shortcut) B.A. degree. Back then, I saw a lot of Sikhs in the Punj Darya office, since they ran a Punjabi magazine too. So there was a lot of to-and-fro, many contacts between the people. Their script is Gurmukhi — which I learnt in ‘86, having been advised that if I was to dedicate myself to Punjabi literature, I had to learn Gurumukhi. It’s a very scientific script: the pronunciations are very clear. It has 35 letters that capture the sounds of Punjabi quite precisely. We can’t adopt it, and most of us, including myself, do our own writing in Shahmukhi. It isn’t as scientific: there are some issues with sounds, and it isn’t computer-friendly either — we have to make special software for it. However, Gurumukhi exists on MS Word.

Anyway, I definitely met a lot of famous people in Vancouver. Ajmer Rode is I believe the most famous among them, a poet who writes in Punjabi and English. I went to his house; he’d hosted a party for me. There, I also met a man, Sadhu Binning — a leader-type. There’s even a street in Vancouver named for him. He’s done a lot of important work for Punjabi in schools, in making it a formal subject in Vancouver's schools. He’s really revered. I met countless people just like them, and of course, it benefitted me a lot.

RSK: As an outsider to this literary world, it does appear to me that much of the current interest in Punjabi literature emerges from the Sikh community. Punjabi is of course the language of their scripture; it does not have that status it does here in Pakistani Punjab that it does among them. It also somewhat seems to me that public literary events about Punjabi language and literature are limited to Lahore. Given that technically Pakistan’s Punjab has higher living standards than the smaller Indian Punjab, it’s interesting that the Punjabi publishing world in Pakistan does not really interact so much with the cities or towns outside of Lahore. What are your thoughts on this?

ZA: You’re quite right about the publishing industry here. The problem is that our alienation — the Muslim Punjabi’s alienation — is something that begins with annexation of the Punjab in 1849. The British, due to their constitution, were committed to introducing local languages as a medium of instruction: in Sindh, they introduced Sindhi, in U.P., they introduced Urdu. In Punjab, though, they had a very famous debate. They called Punjabi a ‘rustic’ language, an ‘undeveloped’ language — something like that was determined by a Deputy Commissioner. Overnight, they imposed Urdu as the language of Punjab. It has now been 175 years since Punjabis have been mired in that alienation from our language, from our culture — in a sense, from our land itself. It’s the talk of the globe now that language isn’t just communication: it’s a reservoir of collective consciousness, of unconsciousness, of memory, of folklore, of so much that has accumulated over centuries. It’s through language that a people survive and come to be — in speaking a language, in doing science in it, in producing knowledge within it. Even now, there are old mothers who know to give cilantro if someone has a fever; ever since this ‘organic’ fad started, people are becoming more aware that not all of that knowledge was stupid. It really was beneficial. And like so many things about our language, it’s all fading away.

A big fraud the British pulled was the styling of Punjabi as a ‘vernacular’. They said Urdu was the language of Muslims, while Gurumukhi was the language of Sikhs.

Then, in ‘47, when the new state came into being, many of those colonial policies were continued. I always say that we love to hate our language. Our erstwhile aristocracy, our ruling classes, our ashrafiya — as soon as Urdu was imposed on us, they accepted it. And a really important premise of that acceptance was the domination of Persian for 800 years of Punjab’s history. Urdu emerged from Persian, and within it, our aristocracy sought the fragrances of Persian, of those 800 years of governance — even though the British occupation had already started, even though we had already become slaves.

A big fraud the British pulled was the styling of Punjabi as a ‘vernacular’. They said Urdu was the language of Muslims, while Gurumukhi was the language of Sikhs. They introduced Gurumukhi for educational purposes. Even within it, it was religious literature that they introduced — the writings of Guru Nanak, from the Granth — not secular literature. Then in the ‘20s and ‘30s, the disputes between Urdu and Hindi came into fore.

As late as the 1970s, in our Punjab, people who were writing in Punjabi were being called members of the ‘Indo-Soviet’ lobby, ‘traitors’ — being told that the language they were working with was the language of Sikhs. Someone should ask them: our first poet was Baba Farid, from the 12th or 13th century, at a time there was no name or sign of Chaucer in English. And there was not even remotely such a thing as ‘Urdu’. Then came Guru Nanak, born in a small village of mere earth and dust. That villager wrote such a thick book that still exists today.

Has anybody ever wondered how such a man was born in some village? Then there are Shah Hussain, Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah — all of these people came, all of them Muslim. They had studied Arabic and Persian, and you can tell how well-studied they were by the vocabulary they lean on in their poetry. If these people were all Muslim, then whose language is Punjabi? Sikhs have only Guru Nanak; we have so many poets, quite a list of dervishes. It's all these false assertions; that is why we are still in this calamity of alienation. Until we escape it, this business of reading and writing, of this limited publishing world — it will remain limited.

I'll add one small thing. Right now, there are many Pakistani English writers at the top of their form. If you do a little analysis of them, you’ll find that all of them are Punjabi: Mohsin Hamid, Daniyal Mueenuddin, Mohammed Hanif and even Nadeem Aslam in England. Many of them have received critical acclaim abroad, and all of them are writing in English. Who is writing in Punjabi? All who's left are the people like me, ha!

RSK: This conversation is reminding me of one of your stories, Paani Di Kundh. In it your narrator is travelling around Indian Punjab and wonders, “Suntaali mukda kyoon nahi?” (Why does ‘47 continue to affect me, why am I not able to move beyond it?) I find that this quality of nostalgia — this really overwhelming sentimentalism in some sense — appears in many of your stories. I wonder, do you have something you wish to achieve within your reader through all these deep immersions into nostalgia, into the past?

ZA: I’d differ with you and others who call my stories ‘nostalgic’. My first story in the Kabootar collection is Murda Taari, in which my narrator goes to his old neighbourhood. No one recognises him. It rains, it becomes evening, plaster cracks from the walls. Then a woman drives by in a car, and the narrator wonders if he knows or doesn’t know this woman — if she was that girl he once harboured a one-sided love for. Then, he recalls more, and thinks of Rome.

Murda Taari begins with the present, with the narrator reminiscing from within the present. There is always a ‘problem’ within a story. To address his problem, my narrator travels to the past. Then he comes back to the present. As such, I wouldn’t characterise it as ‘nostalgia’: the narrator is trying to show you the people and places that he is interacting with in the present have a past; he’s trying to show the undercurrents always at work. In psychology, especially in Jung, it’s said that 95% of our self lies within the unconscious. Both Freud and Jung say that a man’s struggle in this world is that of the unconscious bearing weight on the conscious. All your phobias, all your nightmares, all your complexes — all of them come from the unconscious. Therapy is a means to make them conscious, to get rid of them. I also like to go into the unconscious of a character; I try to dig into it. Then I return to the conscious. The ending line of Murda Taari is something a lot of my friends appreciated. As the narrator passes by the house of his ‘girlfriend’, he hears a voice say: “Ja Bairy, jaa ghar jaa keh saun jaa!” (Go Bairy, go sleep in your house!)

‘Bairy’ was my real nickname. In that entire story, he is trying to look for his childhood home. But he isn’t able to find it. So in whose house can he go and sleep?

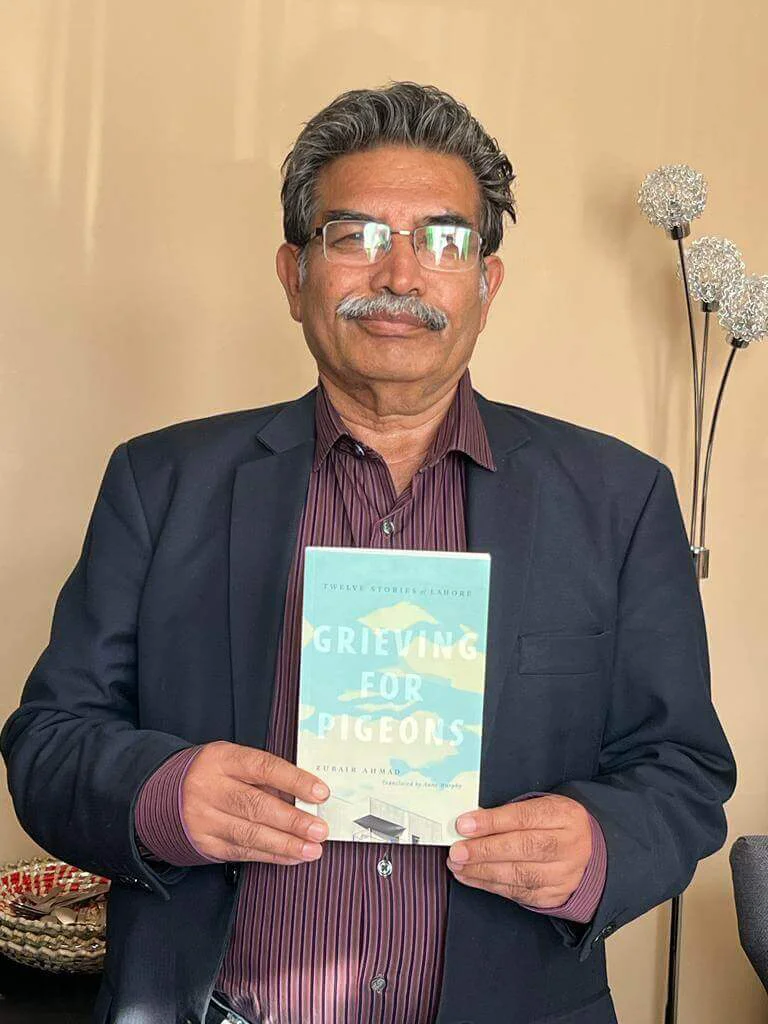

A lot of people approached me because of the English translation (of Grieving for Pigeons) — that’s the brilliance of English, of how many doors it opens. Before that I was just a writer of Punjabi, nobody knew me.

You mentioned Paani Di Kundh. I was born in ‘58 — I haven’t seen Partition. So why does it dwell within me? In that story, I say that Partition hasn’t ended, that generation to generation, the Partition travels. I was raised by a single mother and very attached to her, as my father passed away when I was only six. You must have noticed from my stories that my mother appears a lot in them. My mother was my everything: she was my master; my father; my sister.

Paani Di Kundh is a story of a son who goes to India. He hasn’t witnessed Partition, but still carries a lot of baggage of the past. His mother had said to him that he must make sure — if he were to go to India — that he sees certain things. And when he’s there, he has a dream of steps that go up to a house in the city, in Batala. He sees in that dream a little girl running up the steps, about 10 or 11 years old. Flanking the little girl on either side are the many people of her family, watching on. She keeps running up the steps, until, like a bird, she disappears from his point of view. When I was in that city, I felt the soul of that little girl come along with me. I was afflicted by that presence.

At the end of the story, the narrator relates how when he came back to Amritsar, where he is staying, from Batala, he suspects a Sikh gatekeeper at his guesthouse to be a spy. But the two resolve their suspicions of one another; they become friends, exchange a lot of affection. When my narrator finally leaves the country, when he makes the border crossing, he tells the reader that he leaves behind a ray of sunshine in the pocket of that gatekeeper. Once he is back in Krishan Nagar, when he is dreaming, he can no longer tell if it is his own neighbourhood that he sees in his dreams, or the neighbourhoods of Batala.

They are never going to let us meet, because of the Partition, because of everything else. But in dreams, Krishan Nagar and Batala can become one. It’s basically an anti-Partition story, and a statement that the Partition never ends. Only then can the pain of Partition be undone: when we are allowed to meet, when we are allowed to travel back to our old homes, to our old neighbourhoods — both us and people on the other side.

RSK: This aspect of dreams is something I find very fascinating about your fiction. Your stories appear to begin in realism, and you’ve already talked about how the unconscious is something you seek to unravel. But the degree of strangeness the dreams introduce is something entirely unpredictable — if I ever pass by Chauburji again, I will always imagine a fountain from which fish come out and explode. Can you talk a bit about these ‘dream’ worlds?

ZA: The first story I published was in 1990, but my first book was published in 2001: Meenh, Boohey Te Barian. At that time, I felt that a lot of the stories being written in Punjabi were flat: a beginning, a middle, an end. I did not want to write like that. I did not want to write a purely realistic story. Even now, that’s what I try to avoid. Like the surrealists, I make sure to go into dreams, because I think dreams are a way for us to express things.

Dreams happen all the time in a lot of our older literature and storytelling traditions: the story of Zuleikha and Hazrat Yusuf; Saif-ul-Malook in Mian Muhammad Baksh’s work; and of course the Greek myths are replete with dreams. In fact, I would say Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams is one of the best ten books of the 20th century — he allegedly analysed 62,000 dreams to write that book.

Pure realism is something I find dull. People say that Kafka ended realism in European literature, that it remained in the eras of Dickens, of Thackerary, of Tolstoy. We too should try to get out of it, to be experimental. I don't say that I've done a lot of experiments in my stories, but I do try.

RSK: Something I'm also curious about is the way masculinity is presented in your fiction. Your male characters have a sensitivity that seems quite unusual when thinking about a Punjabi 'masculinity', or even when more broadly imagining South Asian fiction in general. How much is this way of interacting with gender an active choice in your storytelling?

ZA: I don’t understand your question. I have been told by some readers that my fiction is chauvinistic, although most of my stories are about my mother, and women dominate within them. I am not interested in the typical Punjab ‘masculinity’. I am strictly against Jutti, gangsterism — that singer who was murdered, Sidhu Moosewala — that is not the kind of Punjabi man who appears in my fiction. My characters are often humane and sensitive. But it isn't a conscious decision I make. Actually, when I am writing a story and the character is in my mind, I am discovering the character; it isn’t so much that I am building them to become the characters that I want them to be. A lot of my characters — not most of them, but a lot of them — I think can be imagined as ‘real’ characters. There’s something that James Joyce said: “I have written because I love my people”. And by ‘my people’, I mean the people I grew up around, in the alleys and the neighbourhoods where I spent my childhood, my college life — that special time in the Lahore of the early and mid ‘70s. It is because of the love I have for the people I knew back then that I became a writer.

RSK: I also want to ask: across your stories, a first-person, ‘I’ narrator tells us the story. This ‘I’ often leans heavily on your own life-experiences. I imagine many writers utilise the third-person or discover other characters to be more expressive, to be less vulnerable. You live in this city that you write about, interact with people who are both relevant to your fiction and your reality. How do you navigate these choices?

ZA: In all of my stories, there is an ‘I’. That ‘I’ is not Zubair Ahmad: I have entrapped that ‘I’, I have coined and created him to write my stories, to tell those stories. He isn’t the real Zubair Ahmad. But he is me and he is also not me — he is someone moulded to fit the functioning of a story. But why deploy this first-person ‘I’ at all? In earlier eras, fiction was written from a third-person, singular. People used to ask the writer: how do you know all this? Then, in the 20th century writers, particularly Somerset Maugham, wrote many stories using an ‘I’ character. There are some stories in which I have used the third-person and adopted the position of a more conventional storyteller. But my ‘I’ narrator is also my construction — he is part of the story that is unfolding for the reader, a character. Some people are able to understand this, while some people are not. Those others, I don’t talk to them.

RSK: How would you say that winning the Dhahan Prize has aided in your evolution as a writer, changed your engagements with the literary world?

ZA: The first time I won it was 2014 and it was entirely by chance. My book was, in fact, finished and ready for publication back in 2011. But I wanted our famous painter, Sabir Nazar, to do the illustration for my cover. I sent him my story, Kabootar, Baneire Te Galian. He absolutely loved it, and was very eager to do the cover illustration. He ended up taking two years to finish that illustration. Every six months, I would ask him if he was done. But I didn’t want to push him too much, since he was obliging me by agreeing to the illustration — he is such a preeminent painter, after all. And when it was done, I thought it was the loveliest piece of art, that it made my book look so very pretty.

I believe a Punjabi movement today has to be a language movement, rather than an ethnic movement, and its literature has to be read by those who are seeking to lead that movement. They should at least read it a little.

It was the folks at Sanjh Publishers who got it published in 2013, after the illustration was ready. Then it won the Dhahan Prize. All of a sudden, I became very famous; there was a lot written about the book, about the award. I wrote my first book in 2001, Meenh, Boohey, Te Barian. It was my first book, and still very close to my heart, but there was absolutely nothing written about it — no reviews written, no assurances given, nothing.

In 2014, I came into contact with Anne Murphy, who was the Vice-Chairman of the Dhahan Prize committee. Before that, I had been translated into English by Moazzam Sheikh, a writer and translator based in California. I had also given my story, Meenh, Boohey, Te Barian, to Nirupama Dutt, who included it in an anthology of translated Punjabi stories published by Penguin India. I believe I was the only writer in it from Pakistani Punjab. That brought me new attention.

Eventually, Anne Murphy wanted to do an entire book on my own stories. It took about ten years, since she’s a full professor at the University of British Columbia and we only worked on it during the summers. She was adamant that she didn’t want it to be published in India, that it either had to be Canada or the United States. The process of finding a publisher took an additional two years, so it was finally in 2022 that the book, Grieving For Pigeons, was published. I facilitated its local edition’s publication through Readings. They printed 1100 copies and in about a year, the book was sold out. What you see now in bookstores is the second edition. A lot of people approached me because of the English translation — that’s the brilliance of English, of how many doors it opens. Before that I was just a writer of Punjabi, nobody knew me.

RSK: Thinking about readerships, in Punjab, have you ever encountered a space outside of Lahore in which you have been surprised by the intensity with which people are reading novels or are intellectualising Punjabi literature?

ZA: There is a Punjabi literary festival that takes place in Faisalabad, organised by Touheed Chattha and his wife Khola Cheema. It’s a very famous event that’s been happening for ten or eleven years. We set up a stall of Punjabi books there, and they sell! Outside of Lahore, in fact, books do sell, and ours are ordered and taken to quite a few places: Gujranwala, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi and Islamabad. The institution of the ‘Mother Tongue Day’ has helped as well, as it is celebrated with quite a lot of gusto in many cities in Punjab. It’s a really good day, February 21st. We were the ones who drew attention to it at the Press Club in Lahore, in 2013.

It has something to do with Pakistan, as a matter of fact — with the massacre of Bengali students in 1952. They were demanding recognition of their language, and six boys were shot down at a demonstration. The Bengalis started writing letters to the United Nations, and it is to commemorate the sacrifice of those six students that the world today celebrates the ‘Mother Tongue Day’.

I suppose the other thing that’s changed in my lifetime is the widespread use of social media. But most people who are active or are writing on social media are very ignorant people, fixated on generating likes and engagements. My own teachers back in the ‘70s were very different people, very widely-read: all-around philosophers, intellectuals, teachers. Even now, their books are being read. On social media, though, there are some people who have taken on spearheading the banner of Punjabi nationalism, although they don’t have a background or rigour that justifies their pretences. I believe a Punjabi movement today has to be a language movement, rather than an ethnic movement, and its literature has to be read by those who are seeking to lead that movement. They should at least read it a little. It is, after all, a 1000-year old language, with a long history of contributors.

You see, when I had just started to write, people said that there are no stories in Punjabi. I decided: I’ll write the stories. And I wrote three short story collections. Another is going to be published next year (2026); at present, I’m working on a novel. They say: “Apney hissey ki shamma jalaatey jao” (keep alight the candle that is yours to tend). In that respect, what I could do, I have done.