I first met Zain Ali on a Friday night, at a dinner to kick off the ‘Sustainable Fashion and Textile Symposium’ he was curating for the British Council Pakistan. The 33-year-old fashion designer was decidedly less brooding and serious than his socials suggested. He was wearing the ‘Powick’ trousers from his own label, ZN ALI (easy to spot because of the ties at the hem), giving a fun twist to his all-black outfit. “I just wear my own stuff,” he later tells me, “but that’s not because I’m so obsessed with my brand, it’s just easy, and I have all these samples that I don’t want to waste.”

“I don’t think there’s any distinction [between his online persona and who he really is],” he tells me when we meet again. “I’m very open about the things I believe in; I don’t think anyone’s surprised. I do hear that I’m very mysterious, but I’m so confused by that. I don’t think I’m mysterious at all,” he continues, laughing. “I mean, yes, I’m intensely philosophical and I love to have intense, deep chats — but I’m fun, I’m a party girl, as you know,” he proclaims in the way a wry British professor might. “I mean, 11 pm bedtime party girl. Daytime party girl. Mint margaritas and coffees. I need to get sh** done, you know? I need my sleep!”

Zain did not arrive at this moment via a linear path. Born in Lahore, he spent his first years “playing in the streets” around his multi-family home on Nisbet Road, surrounded by cousins and aunts. “Nisbet Road is a big part of my childhood memories,” he shares, “it’s the only thing that’s left from what we left behind.” The happy memories were swapped with “a lot of sadness and struggle” when his mother took the brave step to move her family to the UK when Zain was six, with the hopes of a better life for her four children.

Initially living in East London, the family moved to Morecambe, a small coastal town in Northern England, when Zain was 11, and got a bed and breakfast. Is that as charming as it sounds? He is impressively diplomatic in the way he answers that; while Morecambe was “a very beautiful place”, it was “very white, right-wing, and racist”. It made headline news that “a brown family” had opened a local business and his parents would get calls and death threats every day. “It’s normal to expect racism from kids but I had brutal, quite physically violent experiences not only from students but my teachers,” he recalls.

Always in pursuit of the silver lining, he goes on to describe how his family grew really close because they had to protect and be there for each other. A “kind” and “layered” teacher who taught Zain ‘Ethics and Philosophy’ at A-Level inspired him to pursue the subject at King’s College London for his BA. After that he then went to law school (“I wanted to be a human rights lawyer and so I joined a mental health charity called Mind”). His role was to be the ‘appropriate adult’ and guard the interests of any vulnerable person who had been arrested, be it a juvenile or someone “presenting mental health difficulties”.

The charity was so impressed with his work, they began funding his training to be a clinical psychologist. He was struggling to afford to pay for his legal education and so decided to give it a try. While at Mind he was nominated to consult for governments in Japan and South East Asian countries on youth related issues. With the frequent travel came another career pivot (“I thought ‘wow, I’m really having fun applying my knowledge globally’ so I decided to join the Foreign Office, I applied and I got in as a diplomat”).

This coincided with Theresa May being elected and a right-wing sentiment in Britain becoming more prominent. Subsequently, he found the Foreign Office training deeply racist and eventually decided to back out. “I thought, ‘I haven’t worked this hard in my life, educated myself this much, and compromised not having a corporate career, just to do a career which doesn’t align with my values completely’, so I thought, ‘f*ck this shit, I’m not doing this.’”

Zain’s parents were visiting Pakistan at the time, and noticing his confusion about his decision, invited him to join them so he could figure things out. Once in Pakistan, he began to engage with more of the creative things he had always wanted to pursue but had had to deny himself. “It was the beginning of my career as I know it now,” states Zain.

Prior to this break, he emphasises he “had no creative outlet” and that “(his) career was serious: fighting with police all day, reading legal rights, visiting knife crime youth at 2 am, getting them out of hostels”. The work consumed him entirely to the point that the things he had wanted to prioritise for himself seemed “insignificant” in comparison. In Pakistan he began sharing things he was making and his perspective on Instagram. “A lot of these images began to get attention and spearheaded my creative career,” he says.

These few years in Lahore gave Zain a sense of who he was as an artist and while he had a wonderful time, he felt like “Lahore was not giving [him] the entirety of who [he] was”; serendipitously, he caught the last flight out of Lahore before COVID-19 lockdowns hit. Back in England, he joined the Young Foundation as a programme manager, launching a grant scheme for predominantly Bengali communities to develop initiatives responding to COVID-19. Zain recalls how he had missed working in social impact and community development, but also realised that no grant or organisation would give him the freedom and outlet to truly express himself. So, it was during COVID that he launched his own brand, while still working at the Young Foundation. “Up until this day, I have always had a full-time job and run my brand — I’ve always had two simultaneous careers,” he states.

For Zain Ali, the only things out of style are disconnection, invulnerability and binary thinking. Like the architectural composition of his outfits, he believes one should have values to give us shape and substance, but, like good design, we should be able to move with the times and as the occasion demands.

After the Young Foundation, he began work at the British Fashion Council as a programme lead for The Circular Fashion Innovation Network – “it was about how we can support the British retail industry in making a transition towards net zero initiatives,” Zain explains. “So that’s when I pivoted into not just fashion but also fashion and textile sustainability,” he sums up.

There we have it: the “really complicated story” of how Zain Ali arrived at fashion and sustainability via human rights law, clinical psychology, the British Foreign Office, art direction and COVID-response grant schemes. He spent the summer of 2025 travelling, visiting friends in New York, attending a friend’s wedding in Uganda, back in England then back in Lahore for the Symposium. “It’s been insane,” he concurs when I say I feel like I need to rest on his behalf, “but I’m a triple fire sign.” (There were a lot of astrological references peppered very matter-of-factly in our conversation.)

*

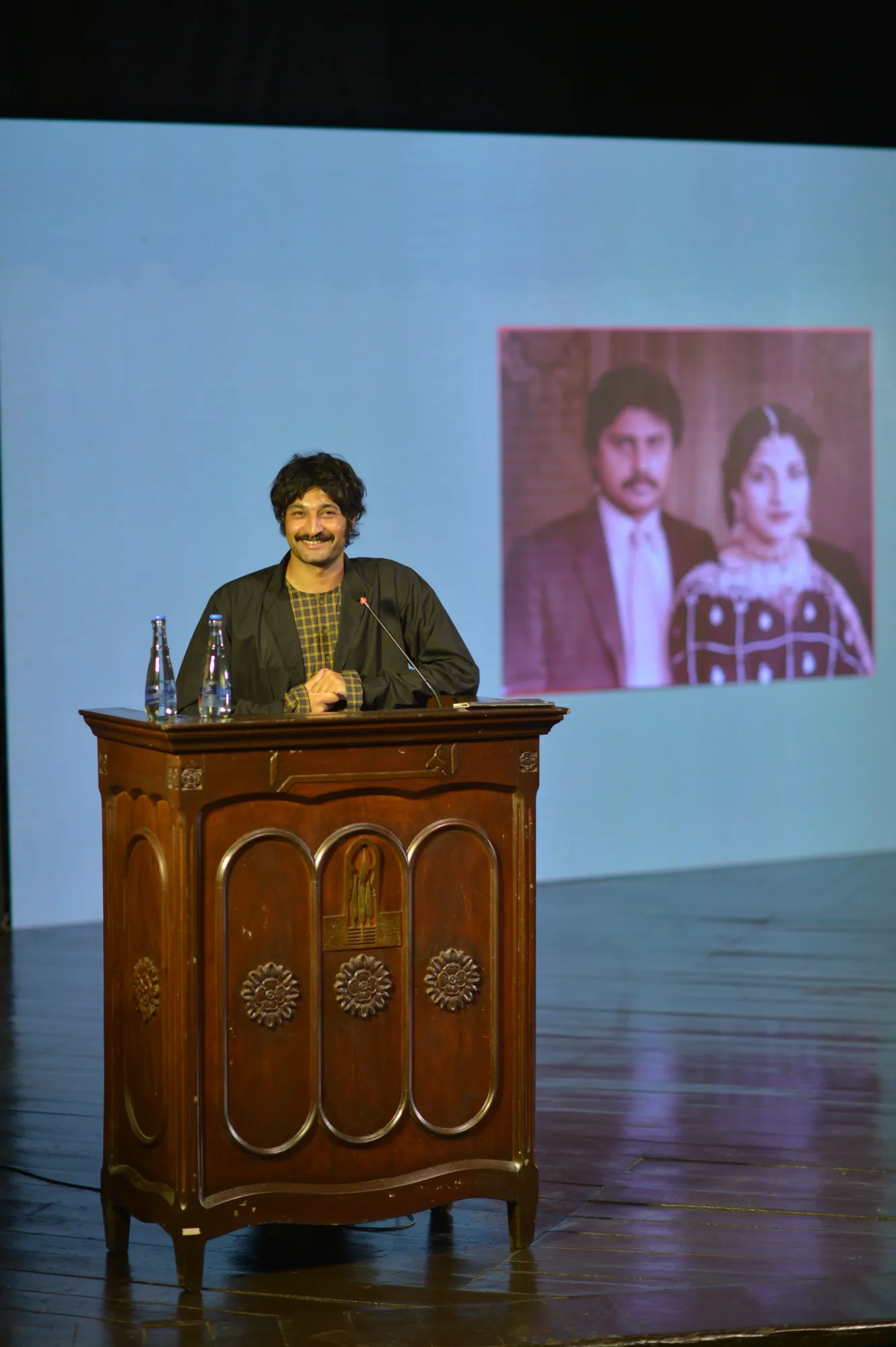

In his opening words for the sustainability Symposium he curated (Lahore, September 2025), which he appropriately titled ‘Moving the Needle’, he reminded us that “textiles embody a personal love story for all of us”. The textile practitioner and counsellor Mashal Chaudhri then prompted the audience to engage with a textile through touch, smell and hearing. She then asked us our intention for being there, and which material we remembered from our childhood; the audience then had to share our answers with our neighbours, effectively breaking the ice and drawing out an embodied, intentional awareness within each of us.

“My curatorial vision for it was for people to connect with what we’re talking about from a very personal space, so I think we had to start with an opening that allowed people to feel vulnerable,” Zain explains. When I ask him what material he remembers from his childhood, he responds, pensively: “You know, because my family migrated so much, and the nature of our migration was so haphazard and chaotic, we often had to leave overnight, that I connected to it from the lack of, rather than abundance of.”

The Symposium’s first panel comprised a decidedly unexpected, but welcome, pair: the legendary architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz and the environmentalist and ex-CEO of WWF Pakistan Ali Hassan Habib. “I know Kamil Khan Mumtaz’s nature,” Zain explains, with a hint of glee, “I thought he was going to allow people to feel a little uncomfortable.” Zain purposefully invited “the architects, the ecologists, the engineers, the manufacturers, the artisans, the crafts people” because “this is a much bigger conversation than just textiles” and because “there’s a universal design philosophy that can travel through everything”.

As expected, Kamil Khan Mumtaz did not hold back: “In the present times, we are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction of species, the cause of which is human activity.” He called our addiction to fast fashion and keeping up with trends “suicidal” and “part of the problem of modernity”. In order to boost sales, the fashion industry deceives us into believing “you’re different, you deserve this, tum hi to ho, dil mange aur, look I’m a modern person”, continued Kamil Khan Mumtaz. Clothes, he sharply reprimanded the audience, are meant to communicate the objective reality of who we are, not our ego.

“One really important thing we learned,” Zain reflects, “is that across the world, across different cultures and civilisations, the modern day term for sustainability has different understandings – in the UK it’s about new fibres and how tech can reduce emissions.” But in Pakistan sustainability is considered “synonymous with craft”. He questions this synonymity: “Why is craft the only path to sustainability? We are one of the largest manufacturing hubs in the world, we cannot ignore or deny that. Why can’t we also allow ourselves to imagine Pakistan as a place where we are also turning toward innovation and investing in technology for good?” He applauds the work of Hasnain Lilani, the founder of Datini Fibres, a sustainable fashion company converting discarded wool waste into premium recycled fibres. Hasnain Lilani was part of the ‘Unlocking Innovation’ panel at the Symposium, along with the UK Fashion and Textile Association.

One concluding session from the Symposium, ‘The Ethics of Making’, “really put the bow on everything” and “challenged everything everyone said” according to Zain. Because of our understanding of craft as the path to sustainability, there was a lot of talk at the Symposium of working with artisans or going to underprivileged areas and giving women work. At ‘The Ethics of Making’, with a wonderfully diverse panel, the power dynamics inherent in working with artisans were put under the microscope.

How did he remain so calm during the entire Symposium? He explains how the role of a curator is to give off the energy that you want from others, no matter what you’re feeling inside. He wanted the Symposium to feel “vulnerable and conversational”, so he made sure he didn’t give off a “professional creative vibe”. His relaxed yet focused energy was like a quiet participant during the entire Symposium.

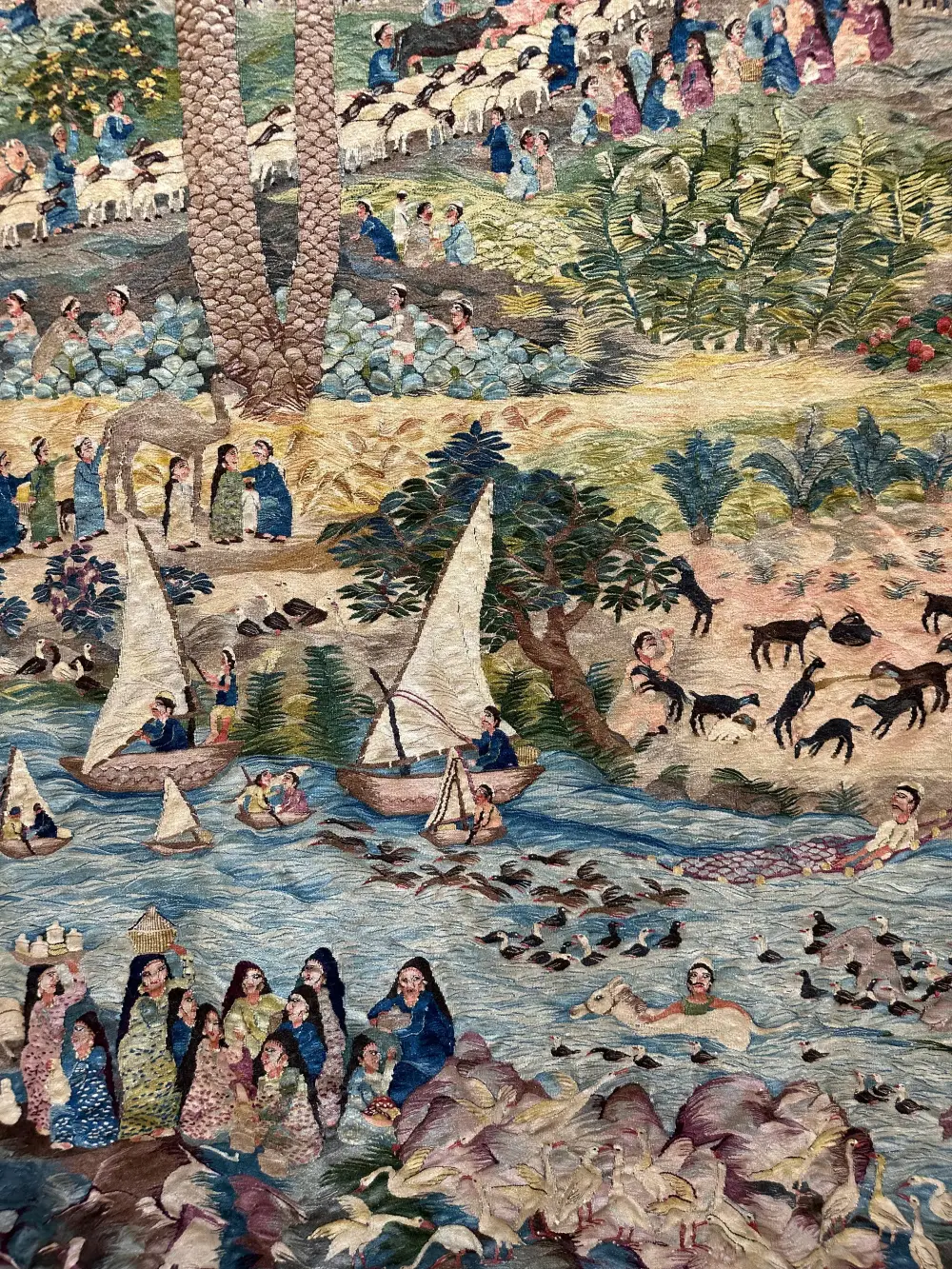

As for how sustainability factors into his own purchasing philosophy, he says he’s “conscious of buying things that have some sort of story to [them]”. The day he visited the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Center in Cairo “was the most transformative day of [his] life in terms of how [he purchases] and also how [he thinks] about design”. The centre, named after the 20th century Egyptian architect who started it, produces naturally dyed and hand-woven carpets woven by local villagers.

“It’s weavers telling the stories of their lives and everything is co-signed by the weaver at the end. I get shivers talking about it and I was crying when I was there.”

He bought a carpet that day and promised himself that “until and unless something makes me feel this way, I’m just not going to buy it”. As for how it influenced his design, the centre made him realise that “beauty has no shortcuts”. Whenever he’s feeling frustrated about production, or about how long things take, he reminds himself that you just have to give it your all, and take your time with it.

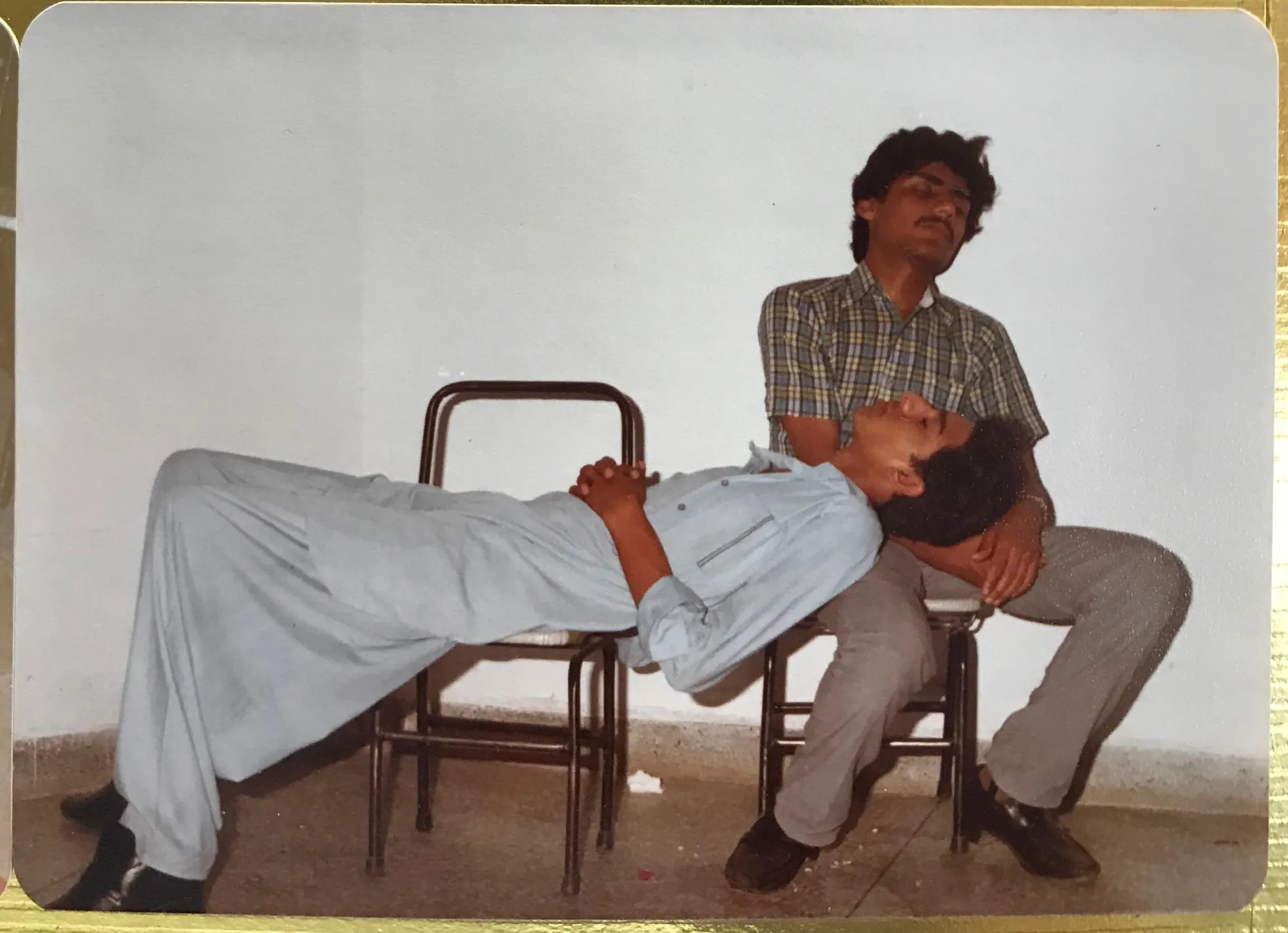

His own label uses handwoven or deadstock fabric; he doesn’t do collections or seasons, he’s inspired by the “modular, efficient and particular” way architects (like Balkrishna Doshi) dress and also by his closest friends. “Most of my clothes that I’ve made are clothes I’ve imagined on a friend or someone I love. All of my models are my friends,” he shares. The first pieces he ever designed were inspired by outfits that his dad, granddad and uncles were wearing in old family photos. That explains his brand’s distinct visual style — high fashion but in your nani’s house. As if 1992 came to visit 2025 and a glam team, stylist and a photographer were present to capture the moment.

For Zain Ali, the only things out of style are disconnection, invulnerability and binary thinking. Like the architectural composition of his outfits, he believes one should have values to give us shape and substance, but, like good design, we should be able to move with the times and as the occasion demands. The only embellishment his designs need is the wearer to be comfortable in their authentic self.

What’s next for this shooting star? Zain Ali’s solo debut exhibition is currently on view at Bradford, UK called ‘Nisbet Road Tailor Shop’ — an installation of what looks like a tailor shop that you can walk around in and view a mix of archival pieces from Bradford museums and his own original designs that he’s made, inspired by historical portraits taken at Belle Vue studios Bradford. He pays homage to the South Asians who immigrated to work in Bradford’s textile mills and opened up tailoring businesses in the 1950s and 60s, and to the resultant British-Asian style that evolved from their presence in the city. His dream is to open his own tailor shop one day, where a customer enters his world and they create something together. ‘Nisbet Road Tailor Shop’ is on till 23 November, 2025. If you can’t see it in person, don’t worry, it’s all over Instagram: the popular culture page NOWNESS just shared a video celebrating its opening.

Photos from ‘Moving the Needle’ by Nad e Ali (courtesy of British Council Pakistan); all other photos courtesy of Zain Ali.