In the early hours of February 13th, 2023, I was awoken by my phone buzzing on my bedside table. This was not the continuous, metronomic buzzing of receiving a phone call but rather, an oddly scattered buzzing which was escalating in tempo: messages were piling up before I could wake up properly, or even extend my hand toward my phone.

Without reading a single message, I already knew what had happened. Mr. Zia Mohyeddin or “Dada Mamoun” as my siblings and cousins called him, had left us.

Days prior, he had been admitted to the hospital after suffering a deadly aneurysm. Family members in Karachi had rushed to the hospital and many were by his side as doctors ably handled the not-enviable burden of saving the life of a living Pakistani legend. His medical team had communicated to us that this time, it really wasn’t looking good.

I remember my heart sinking upon hearing this, but I also remember feeling a strange sense of resolve that he would emerge. Though he was by now ninety-three years old, and had even told me in his early eighties, during my decade long documentation of him, that he had perhaps “a year, a year-and-a-half, maybe two” years left then, he always seemed to emerge from his health issues. And to inevitably resume his classes at the National Academy of Performing Arts (NAPA) in Karachi as soon as he was physically able to.

Though he had admitted to me that he often considered the idea of his own mortality once he became, characteristically quoting Lear “Fourscore and upward”, for many, many years, his work seemingly kept him alive. His response when questioned about the meaning of life was deliberately unglamourous: “Work, work, work…”

In characteristic fashion, at the beginning of this particular bout of ill-health, he had told the doctors to make their treatments as swift and effective as possible, as he was due to appear at the Faiz Festival in Lahore for a performance in less than two weeks.

A month prior to this, he had given what was to be his final performance of the readings of Urdu literature he had become famous for in his later years. Beginning in 1986, the annual Zia Mohyeddin Readings at the Ali Auditorium in Lahore, organised by my father Mr. Naveed Riaz, had become a tradition beloved by many in the city. For thirty-five years, the date, time and venue was always the same: December 31st, 6 PM, Ali Auditorium.

That final year, however, a date change had to be made. My first cousin was getting married in that crucial December holiday time period which would allow guests from abroad to attend the wedding in Pakistan. When my father informed him that we would have to delay the readings by a week, Mr. Zia responded with anger and incredulity: “You are disrupting a thirty-five year tradition, and that too, for all things, a wedding?”

This, of course, was a man who famously married no less than three times in his lifetime.

A week later, him, myself, my father and Mr. Nafees Ahmad - his longtime sitar accompanist - arrived to the light and sound check the morning of January 7th, 2023.

The winter mornings in Lahore are often chilly and inhospitable; if not outright dense with fog, then with a grey mist shrouding all that is visible. Unwelcome, as well, for myself and my father who can’t be called morning people. However, our anxiety, for lack of a better word, would wake us up early enough those mornings, because we knew how crucial punctuality was for Mr. Zia. He would be ready, sharp, suited and donning his customary camel wool overcoat at the agreed meeting time to the second. Not to the minute, not within minutes, but to the second. As his wife at the time of his passing, Azra Mohyeddin, remembers, he spent his days counting in seconds, not minutes.

After graduating film school, I was often drafted in to set the stage lighting. The sound and lights would essentially be set while Mr. Zia was backstage at the auditorium. Once we were “near there”, he would appear at his podium, pause for final light adjustments, read a few sentences for sound adjustments and, often with a little skip, he would be ready to leave and prepare for the performance.

This preparation would begin with lunch at our house (he was particularly fond of koftay), some run-throughs of excerpts with Nafees Sahib (Mr. Zia sometimes hummed his preferred accompanying notes to him), going over notes for the pieces to be read and, finally, a little rest before getting ready to leave for Ali Auditorium. While all of this usually transpired in a relaxed manner, even till the very end, Mr. Zia never took his experience, skill and talent for granted to coast through a performance. By this time, every nuance, every pause, every colouring in or shading of every syllable of every word in every sentence had already been scrutinised and set in place in his mind.

Tea was to be served to him backstage at Ali Auditorium at 5 PM sharp, with a maximum allowance of perhaps ten or fifteen seconds to the server past the 5 PM mark. Then he would pick and choose different excerpts to run-through with Mr. Nafees all over again, making sure recitation and music were to be entirely in simpatico that evening, even though Mr. Zia and Mr. Nafees had not only been performing together for decades, but were colleagues at NAPA as well.

That night, I saw him perform from the second row, to the left, a view I will never forget. My father had delicately asked Mr. Zia not to exert himself too much. He had responded: “Yes, I’ll keep it shorter this time…it’ll go on for about an hour at most…” He ended up performing for more than an hour and a half, standing the whole time, pausing only when the recitations demanded it, not when he needed to rest.

Later, he told my father that after an hour and fifteen minutes, he began to feel his legs give way. While clutching his podium with one hand as if it were part of the performance so the audience would not be able to tell, they almost did. Mr. Nafees gently took him in his embrace as he stepped down from the rostrum, and they made their final bows.

For an actor, it was a tour de force performance revealing the depth and width of Urdu literature, from transcendent poetry to laugh-out-loud humour to genteel yet affecting romance to wrenching, tragic prose. For a ninety-three year old human, it was an extraordinary physical feat, to not just be sound of voice, but strong of voice, to not sit down, to not rest, to respect the sanctity of the stage, the only place where he had felt he ever truly belonged. To let the power of being there, under the lights, in a theatre with four hundred darkened strangers watching him carry him.

Just a month later, he left us.

It is perhaps a strange thing to say, but once he passed away, I felt that it was only in death that Mr. Zia’s rich enduring legacy, his unspoken mission, was truly cemented.

The first indication came when leaders of all major political parties united in an extremely rare moment of agreement to express their condolences and post tributes to him. As my father said to me privately at the time: “This is the kind of respect which is not simply given; it is earned.”

In earning this respect over a nearly seven-decade long career, Mr. Zia kept a quiet purpose thrumming in his heart. He rarely spoke of it out loud, let alone appear in public to broadcast it with strident activism. Simply put, it was for others to continue work like his, for new, capable artists to contribute and keep contributing to the art and culture of Pakistan, to be able to receive the kind of instruction, if not opportunities, that he had in becoming who he became.

Though he had British citizenship and maintained a residence there, throughout his life, Mr. Zia kept returning to work in Pakistan to contribute to this mission. A dream he had since the 1970s, to start a dedicated performing arts academy in Pakistan, finally came to fruition upon the establishing of NAPA in Karachi in the early 2000s at what was then the abandoned but beautiful Hindu Gymkhana building, requested by Mr. Zia himself.

He lived long enough after NAPA started to oversee and guide several batches of students through rigorous training which he supervised personally. When he passed, Mr. Junaid Zuberi, who succeeded him at NAPA, told me, “The students are deeply demoralised today, the air is heavy with grief across campus…”

Every creative practitioner, if they commit to what they do long enough, likely knows that their life and work are intertwined as fingers when holding hands. The particular recitation of Mr. Zia’s which was shared the most on the internet after his passing was Mr. Noon Meem Rashid’s Zindagi Se Darte Ho? The original studio recording from decades ago finds his voice higher in register, emboldened, barely containing a passionate fire within. His later live recitations find the voice deeper and quieter, the emotional crevices of the poem conveyed not by acrobatics of the voice but by its cracks, its quivers, now barely containing the vulnerability within.

For someone often eulogised as ‘The Voice of Pakistan’ after his passing, the evolution of that famous voice was perhaps the humanity in its deterioration, conveying the unrelenting passage of time, the lengthening shadow of mortality, the recurring losses of old friends, past lovers, and family.

In person, Mr. Zia was committedly reserved and insistent on keeping his personal life private. It is my understanding that underpinning this was his enduring wish for Zia Mohyeddin himself to not become a character to audiences. He could, capably at the very least and transcendently at most, turn on a dime to become a young Romeo or “fourscore and upward” Lear and equally so, a gentle and compassionate Faiz, or a metaphysical and passionate Ghalib.

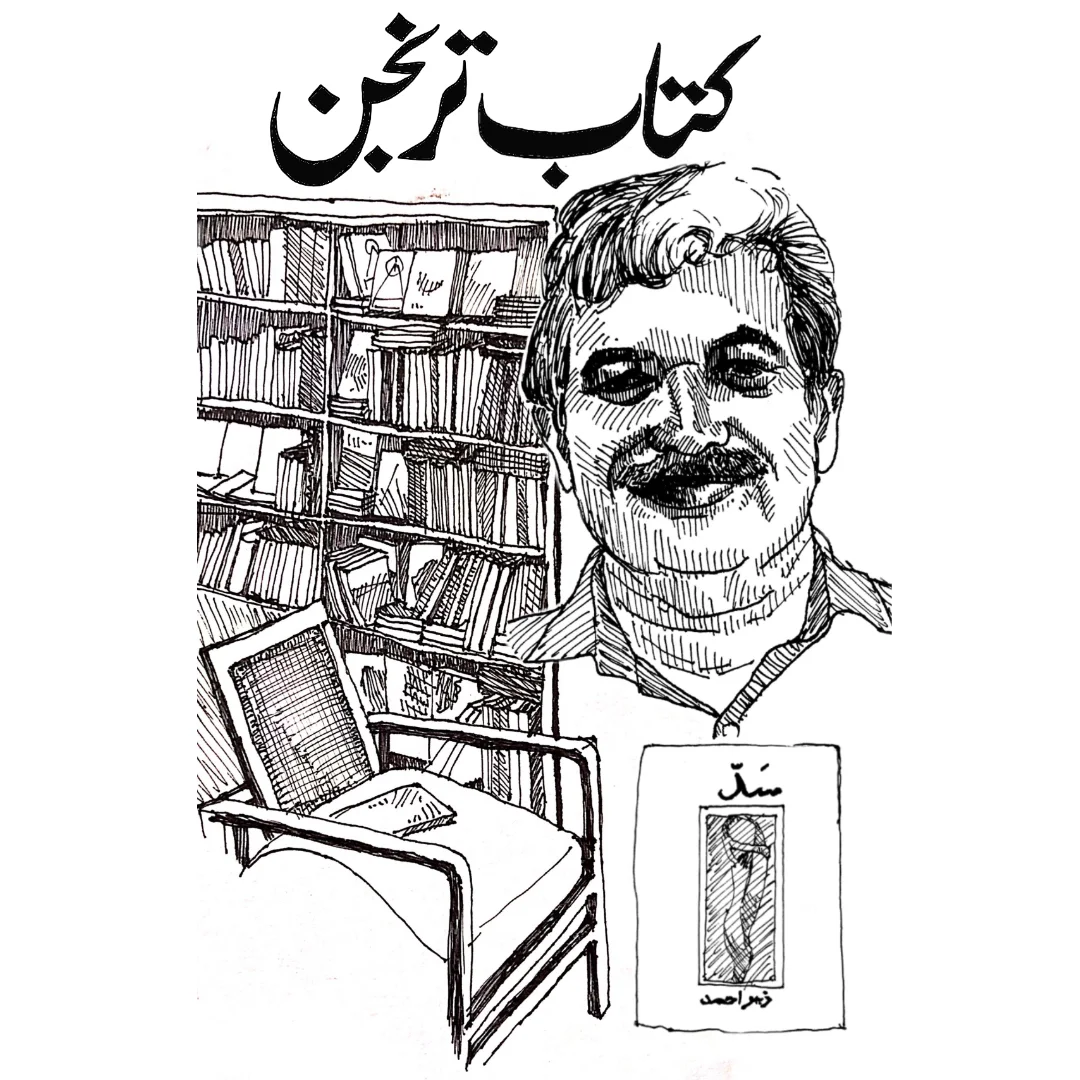

However, Zia Mohyeddin himself rarely socialised, and almost never appeared at public events. He had very few but committed old friendships, by his own admission was “never a family man”, and the place he felt most at home was either in his study, surrounded by walls of his books, or when sneaking into the theatre named after him at NAPA when it was unused and empty, performing by himself on a bare stage to row upon row of empty seats.

Ironically, for such a presence on stage regardless of his five foot four inch, slim-as-a-fiddle frame (for which he was relentlessly bullied when at school), his was anything but a showy personal presence for most of his lifetime. When he tried to be, during the Zia Mohyeddin show, with his flamboyant shirts and catchphrases, the frenzied popularity he received made him quit the show after two seasons, and seek refuge in London for years.

How antithetical this all is to our current age of celebrity and influencer culture where people, especially actors, can easily become brands, sharing their workout routines, breakfast smoothies, beach vacations and designer outfits, their work itself in constant peril of becoming a footnote to a consistent projection of their lives.

Mr. Zia’s unspoken mission, especially in his later years, hinted to me when he recounted his life, was not to keep Zia Mohyeddin forever alive in people’s hearts and minds (though of course this would be inevitable), but instead, to instil the the deep richness of our cultural heritage in the public imagination. The vast reservoir of our prose and poetry, the pathos and catharsis of our theatre, and of course, the elegant piercings of Urdu performed with almost excruciating attention to enunciation and diction.

He once summarised his work “as the rippling of the light and the dark.” He deliberately stayed in the dark to bring the best of our culture - and by extension, ourselves - to light. And perhaps he knew that by stepping off the stage one last time, he would be in the light evermore.