Three people are ushered into a salon in a house in St. James’s Square (London) by a disapproving butler. They are looking for the master of the house, and the only man in the party exchanges unhappy looks with the butler despite his position as a Peer of the realm. The ladies of the party, his wife and mother-in-law, are determined, however, to speak to the man who owns this exclusively situated mansion, their son and brother, respectively, and no man can stop them. Meanwhile, on Hounslow Heath, a carriage is bowling along at night, carrying the seemingly asleep man inside it to a ball when it is set upon by highwaymen. A sudden gunshot rips the air because, without appearing to open his eyes, the carriage’s occupant has shot the robber through his coat pocket and the carriage door. In yet another large house in the Kentish countryside, the old master of the house has yelled at his daughter-in-law to stop gossiping and the silent awkward dinner ensuing is causing the second footman to consider how soon he can leave and join a calmer establishment with more prospects for promotion.

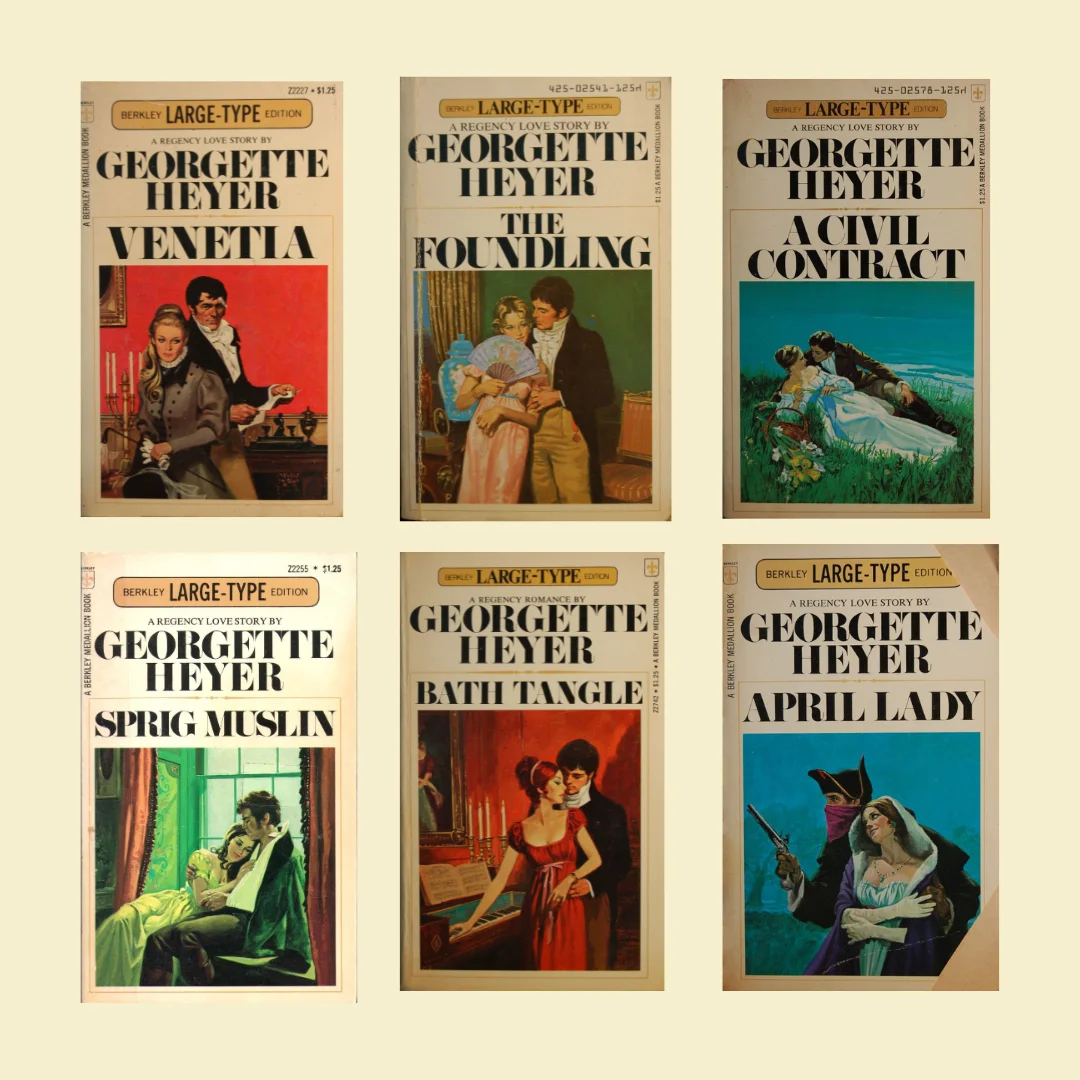

These are all the openings of some of Georgette Heyer’s novels. Writing from 1921 until her death in 1974, Heyer set most of her novels in the Regency period, with several set just before the French Revolution, and a few focusing on individual British monarchs, including William the Conqueror. Heyer may, in fact, have invented the ‘Regency Romance’, a term very familiar to us with the books (and tv shows) of writers like Judith McNaught, Julia Quinn and others. What we get now in the name of Regency romance is a bodice-ripper with a lot of prurient and salacious details, but not necessarily much history. It frequently seems that when a contemporary author wants to add details of male control, balls and big dresses they lazily set their novel in the Regency period, even though the ‘Regency’ is an era in British history and not code for ‘general olden time that you can use for aesthetics in your novel’. For Georgette Heyer, though, the choice of the Regency as the era for most of her novels is a conscious one. Heyer did not come by all her historical details easily. She has penned an afterword citing her sources to several of her books: Heyer read diaries of famous men, generals, society dandies, soldiers and many others. Therefore, when writing about the time that Jane Austen lived in, Heyer brings a view of the era that is not evident in the drawing rooms that Austen was confined to. Here, then, is the world of gambling dens, boxing parlours, the landed gentry’s estates, the French court, army barracks, battlefields, wayside inns and a lot more.

It is one of the strongest features of a Georgette Heyer novel that the full-throttled adventure replete with well-rounded, distinct characters provides the sort of entertainment not found in many romance novels.

Heyer has a rare eye for detail of dress and turns of phrases, especially ‘cant’, the slang marking social divisions, of people like servants, chimney sweeps, thieves and innkeepers. She presents us with these details without belabouring the point or flaunting her learning in any obvious way. It is all part of a background so expertly painted that it complements the main action instead of distracting from it. Thus we know from a short scene in Arabella (1949) depicting young girls talking in a schoolroom that they get their ideas for dresses from the ladies’ magazines that their mother subscribes to, what their birth-order means for them in the larger schemes of their lives, how important it is for their eldest sister to make a good match, the vagaries of social norms, their financial position and much else. This is all even more fascinating because of the pre-internet era that Heyer wrote in, where tracking down descriptions of clothes certainly took time, patience and an uncommon dedication.

Her ‘Regency’ books range over at least 70 years, some technically pre-dating the actual Regency of George III’s son, such as These Old Shades (1926), which is set during the last decades of the French monarchy before the Revolution. Heyer does not shy away from describing her male characters’ high heels, mincing walk, powdered wigs, rouge or face powder, thus putting aside modern biases that trick authors into giving their historical characters modern sensibilities and characteristics (like overt macho-ness).

Heyer presents her characters as she finds them — which is perhaps the secret to their unique personalities — and her narratives are so charming that they persuade us to suspend our biases as well and enjoy the stories. What sets Heyer apart, and by that I mean at the top of this sub-genre, are her characters, stories and historical details. This, despite the density of some of their works, none of her vaunted literary descendants has achieved. Heyer wrote more than 40 books and followed no formula which would allow the reader to predict what would happen next. The plots are unique to each novel and so are the characters; not for Heyer any stock characters reused from one novel to the next. There are dunce-like characteristics that she may award a silly cousin in one novel and the hero in another, where the latter’s simplicity could be paired with a strong sense of responsibility and honour.

Upon recently rereading 15 of the Georgette Heyer novels that I only read once as a teenager (as opposed to some that I’ve reread many times over the years), I found myself especially enjoying A Civil Contract (1961) that I remember not liking as much 20 years ago. It tells the story of Captain Adam Deveril, having newly inherited the title of Viscount Lynton, returning from the Napoleonic Wars to find himself in deep debt thanks to his deceased father’s high-flying lifestyle and ruinous friendship with the Prince Regent. This is the novel, besides the ones dedicated to the Wars, that holds the greatest amount of social detail of the years of the Regency and its effects on the aristocracy. The Viscount, faced with bankruptcy, finds no solution except to marry an heiress, the daughter of a merchant who has social ambitions for his only child. Where teenage me inwardly cringed at the idea of an arranged marriage made for money on one side and social climbing on the other, I found myself now, in my thirties, thoroughly appreciating the world of social subtleties and historical detail, vast in its breadth, understanding and compassion.

What sets Heyer apart, and by that I mean at the top of this sub-genre, are her characters, stories and historical details. This, despite the density of some of their works, none of her vaunted literary descendants has achieved.

A Civil Contract is a rare performance of the sustained interaction between the aristocracy and the nouveau riche. Viscount Lynton’s father-in-law lives in a mansion in Russell Square in London, which has been newly carved out of what was the Bedford Estate, and as a surprise wedding present, purchases the Viscount’s Grosvenor Square mansion, which he has been forced to sell, and returns it to him. Despite Mr. Chawleigh’s ambitions for his daughter, he effaces himself from “polite” society and refuses to attend any balls or parties, citing his “vulgarity” and the fact that he knows his place. But Heyer does not allow him to disappear from the narrative, pursuing him into the City of London to his offices and giving him a starring role, where the competence and consideration underlying his brusque manner are tenderly highlighted.

There is a certain maturity of thought and attitude in this novel that has moved Heyer away from the class dynamics portrayed in earlier novels where the middle class is largely depicted as shrill and grabbing. Sophia Challoner in Devil’s Cub (1932), the result of a mésalliance between a nobleman’s son and a city merchant’s daughter, is set up as a silly, flighty girl, greedy enough to allow the aristocratic protagonist to ruin her. Her sister, meanwhile, is the opposite and the differences in their personalities are set down to them inheriting traits from different sides of the family — Mary, of course, inheriting her father’s aristocratic family’s values. These biases, however, do not jar as much as one would expect because the novel is a hilarious romp and none of the characters are perfect, least of all the hero of the tale. This humour and action are the two main reasons for Heyer’s loyal cult following.

Heyer’s novels have always been marketed as romances, and their covers now are more generically frothy than ever with the unavoidable comparisons to the Bridgerton series, with quotes about gossip and scandal screaming from the covers. But although the heterosexual romances may provide the heart of each novel, their soul lies in the extended relationships with family, friends and servants. Writing between the 1920s and 70s, Heyer did not include any sexuality in her books and this absence serves the reader well. In a world where we are used to the soft pornography punctuating romance novels, and race through the narrative until we reach the intimate scenes, it is difficult to appreciate much else. It is one of the strongest features of a Georgette Heyer novel that the full-throttled adventure replete with well-rounded, distinct characters provides the sort of entertainment not found in many romance novels.