I first noticed this space while driving past it on a busy evening. We were getting off the Islamabad Expressway to take the underpass towards Gulberg Greens and I saw something that caught my eye: a large, vibrant gathering; children running across a green lawn, groups of women walking and some families sitting in loose circles on the grass, as if on a picnic. It is not what you expect to see next to a highway, surrounded by fast moving traffic and car-centric infrastructure.

I kept thinking about it after we drove away. Over the next few weeks, I started noticing it more deliberately; I would glance over whenever I passed by. The first time I saw the park was not some one-off event. In fact, the space was regularly full of people. In a city where public life is often commercialised or exclusive, this was the most vibrant public gathering I had seen anywhere near where I live. It felt both completely unexpected and entirely natural at the same time.

This public space exists in the leftover land between a highway, a looping exit ramp and an underpass, technically known as a ‘cloverleaf island’. It is surrounded by heavy traffic roads, with cars constantly speeding past, honking and weaving in and out of merging lanes. There is noise, smoke and very little to suggest that anyone would want to stop here, let alone come out for a picnic. It is not an easy place to walk to either, with no crossings or pedestrian signals anywhere nearby.

What got me more curious is that it is not technically a park. The place does not have an official name or any such signage; there are no benches, no trees, no walking paths or playground equipment, nothing to suggest that it is a park. But if you ask anyone using the space, they will call it a park—because that’s what it has become.

Public Space, By Demand

Part of what makes this place so popular is what is glaringly missing in nearby neighbourhoods. This public space lies close to many densely populated housing societies that have failed to offer safe, comfortable and accessible public spaces to their residents. You will find a few token green patches inside these societies, but they are often poorly maintained, locked up or at best, just empty lots with overgrown grass—take your pick.

There is a kind of irony to it: these are planned communities, built from scratch, often advertised with words like ‘greens’, and ‘garden’. However, when it comes to basic public infrastructure like parks or footpaths, the planning seems to fall short. In fact, I would argue that the absence of parks and public spaces is what has pushed people toward this green space—not because it was designed to be used as a public space, but because it remains open to all, free and functional.

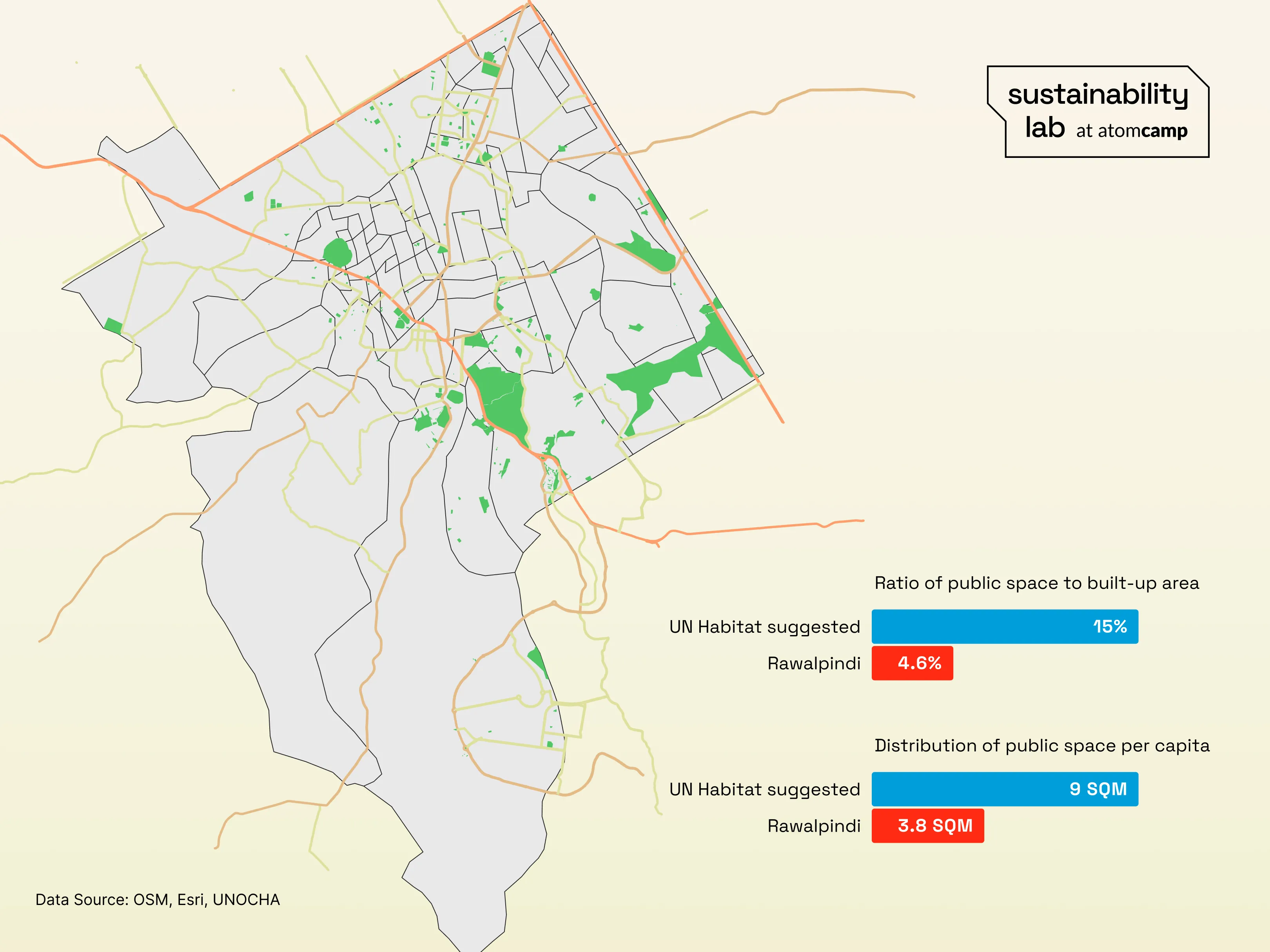

According to UN-Habitat, the recommended minimum amount of green open space is 9 square metres per person. In this part of the city, at the boundary of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, people have access to only 3.8 square metres per person—less than half the suggested minimum! This number comes from a recent study conducted by the Sustainability Lab at atomcamp and it raises an urgent question about how our city is being planned, as well as what kind of spaces we are making room for.

What Makes It Work

I began visiting the space, or ‘park’, to observe more intentionally, in order to understand what made this patch of land feel so alive, even though it was not planned or equipped like a public park. Despite its informality, it serves the role of a park surprisingly well.

Located right off the road, it is not hidden or isolated. The lawns are well-maintained inviting people to sit, play and relax. Hedges help divide the open space into soft ‘rooms’, offering both openness and a sense of enclosure. The area lies in a depression, slightly lower than the surrounding road, which buffers traffic noise. It is open on all sides, with no gates or fences. This openness, combined with visibility from the road, adds a feeling of security. The lawn is large enough to host many groups at once: children playing ball, families picnicking, couples strolling, others just people-watching. Everyone shares the larger space while still having their own little pocket for activity.

One of the most joyful daily scenes in the park is when the water tanker comes to spray the lawns. As it circles the road, it sprays a fine mist over the lawns and children begin to chase it. They run through the water gleefully, turning a routine maintenance task into a moment of play—a refreshing break from the heat and a rare instance where a municipal service becomes a source of delight.

There is light vendor activity too: an ice cream cart, a corn seller, a kulfi wala, a soda stand and someone renting out footballs. Small vendors add convenience and atmosphere without overwhelming the space with food stalls. At the same time, the presence of trimmed lawns, light policing and a designated guardian from Gulberg Greens signals that the space is looked after.

What also stands out is the sense of welcome to the general public. There are no fancy lights, designer benches, or signs that suggest who the space is for. People are relaxed, unbothered by each other and enjoying themselves in public.

But What Does It Say About the City?

Despite the charm of this space, access to it remains a major issue. Families and children have to cross aggressive traffic to get to the park. That people are forced to be in this car-centric environment to access something as basic as a public space is an absurd reality for the twin cities.

This space sits in a traffic island left over from the highway. Not designed for public use, but claimed by the people out of necessity. Since good parks and public spaces are missing from most residential areas, people are forced to turn to unconventional places like this. It is a well-used space, but it reflects a sad state of affairs.

There are interventions that can improve the park as a public space and make it safer. Things such as signage and visual cues to slow down traffic and alert drivers about the park ahead, as well as safe pedestrian crossings. This park is an example of tactical urbanism, a concept where unconventional or overlooked spaces are repurposed for citizens and public use. It is an important case that should be studied and legitimised by the authorities. A case that highlights the urgent need for more accessible, open, and unstructured public spaces and the responsibility of public and private developers to invest in them across the city.