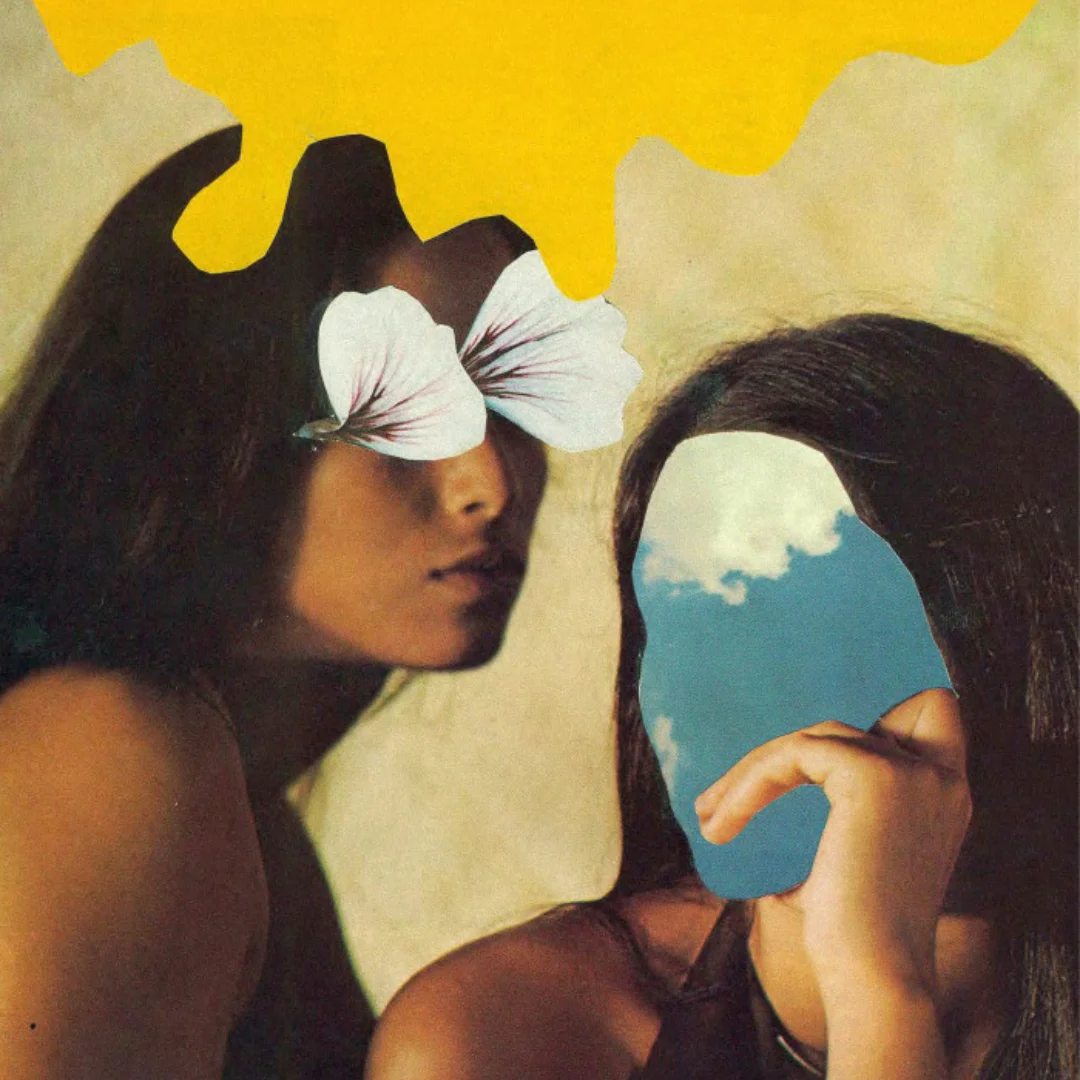

It’s probably the most difficult thing to be a writer in this age of the internet, where nothing can ever be forgotten. For every idea you have, someone else has already thought of it and blogged it on their Wordpress fifteen years ago, and some keyboard cretin will dig it up in a matter of minutes to spite you in the ‘Comments’ section. Gone are the days where you could be inspired by an author in the good old-fashioned way, absorb some of their sensibility for yourself and make your creative way in the world. No, now you have to be startlingly original and a bit weird to prove you are in fact possessed of a human imagination; now your writing has to bamboozle your audience but in the best way, a way that feels modern but employs classic techniques: the figure in the carpet, the lurking shadow behind the shower curtain, a creeping nameless horror. Enter Small Scale Sinners (A Public Space, 2025), Mahreen Sohail’s debut book: a collection of short stories that can only be described as deft, surprising and satisfyingly horrible.

Sohail’s stories are like thinking you’re going to exit a house from the door, but end up jumping through the window instead. You’re outside in any case, but you really didn’t think that’s how you were going to get there.

The third story in the collection, Hair, appeared in Granta 151 (2020) and is probably where you may remember her from. Sohail’s stories are like thinking you’re going to exit a house from the door, but end up jumping through the window instead. You’re outside in any case, but you really didn’t think that’s how you were going to get there.

Bamboozlement, 10/10. In twelve tales, Sohail brings an absolutely unique voice to explore themes that include sisterhood, childhood, marriage, just being a person — thus far, the route to the door — and then, a shift. It’s almost imperceptible, the way the narrative turns, gently skewing it away from the centre and suddenly you’re one leg over the windowsill and absolutely absorbed by the adventure.

Born in Islamabad and now resident in the US, Sohail populates Small Scale Sinners with recognisably desi characters, but set in a world that, quite like Ben Okri’s Nigeria in Incidents at the Shrine (his own first collection of short stories), is Pakistan without overtly naming it. It’s an effective strategy for writers of colour, and both have used it to satisfying advantage. It allows the author to situate their narratives in a familiar emotional and physical geography without having readers jumping to confining, exoticising conclusions about how Other People live. This choice doesn’t shut out a larger audience by being ultra-specific and is a clever nod to readers who are in the know and can recognise the references. Most importantly to the narrative, it blurs the edges of reality.

Weird things can happen in a Not-Pakistan without it being called magical realism or horror, because the prose itself never goes definitively in either direction. The rules don’t apply to ur-citizens of a mirror-country, so ‘normal’ is just whatever is happening. It doesn’t matter if that normal doesn’t look or sound like yours (or more awful: it does). This liminal space is where Small Scale Sinners shines, dark and just intense enough to be unsettling, eerie enough to be horrifying but never tipping the balance one way or another. The moon can shine bright in the night, but “slung like a jack-knife”; the night can smell like water and grass, but you’re outside because little kids are doing terrible, violent things. Technically, you could be anywhere. You’re both at home and in the strangest place you’ve ever been. Perhaps there has never been a more appropriate way to make sense of the current world than this.

Interestingly, people don’t have names in the stories. Protagonists are “your mother”, “the girl”, sometimes Mrs Rafique — but nobody of importance has an actual name. This gives the stories a coherence, a sense of sliding from one situation to another without distinction that makes the overall experience of reading the book feel like one long sitting, one evening of a story that led to another, Sheherazade-like. And like the Arabian Nights, there aren’t always happy endings.

It is often nighttime, there are often weird and strange things happening, and they are most often happening because of young women: a woman on the edge of spinsterhood tries to (actually, physically) fly with the homeless guy across the road; the alluring twins at an all-girls school are surrounded by some rather intense school-friends; newlyweds find themselves hosting a lunch that takes an unnerving turn; a mother and daughter with a unique vocation move into a new house.

This liminal space is where Small Scale Sinners shines, dark and just intense enough to be unsettling, eerie enough to be horrifying but never tipping the balance one way or another.

Sohail paints ordinary life with an observant eye and flair for identifying the uncanny beneath the normal that we ordinarily expect from horror writing; that ability to capture a discordant note without making it obvious. It’s a welcome breath of freshness; a Pakistani writer who is neither self-conscious about being ‘ethnic’, nor easily pigeonholed by genre. Sohail wears her imagination lightly, brings her ‘strong women’ to life inconspicuously and gently dislocates her readers in what is, overall, a deeply enjoyable read.