Growing up in and around Lahore the way I have — in disjointed, nonlinear fragments — has deeply affected how I make (or rather, can’t make) sense of the spatial development in my hometown. Each time I’ve returned to the city after time away, I’ve felt like it’s taken new shape or form in my absence. Some new shiny underpass, flyover and other what-not-accruement adorns the city’s canvas, almost feeling like a personal jab directed at you. As if the city took affront to your brief detour, and hence took it upon itself to teach you a lesson by becoming unrecognisable when you decided to step out of its labyrinth. That a metropolis the size and magnitude of Lahore shapeshifts frequently shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone, let alone its own inhabitants, but more often than not it is the very people who live within its perimeters who are left most wistful whenever a new infrastructural development occurs. The wistfulness is magnified when some (or most) of us have not been a part of, or deliberately left out, of the decision-making process of said development(s).

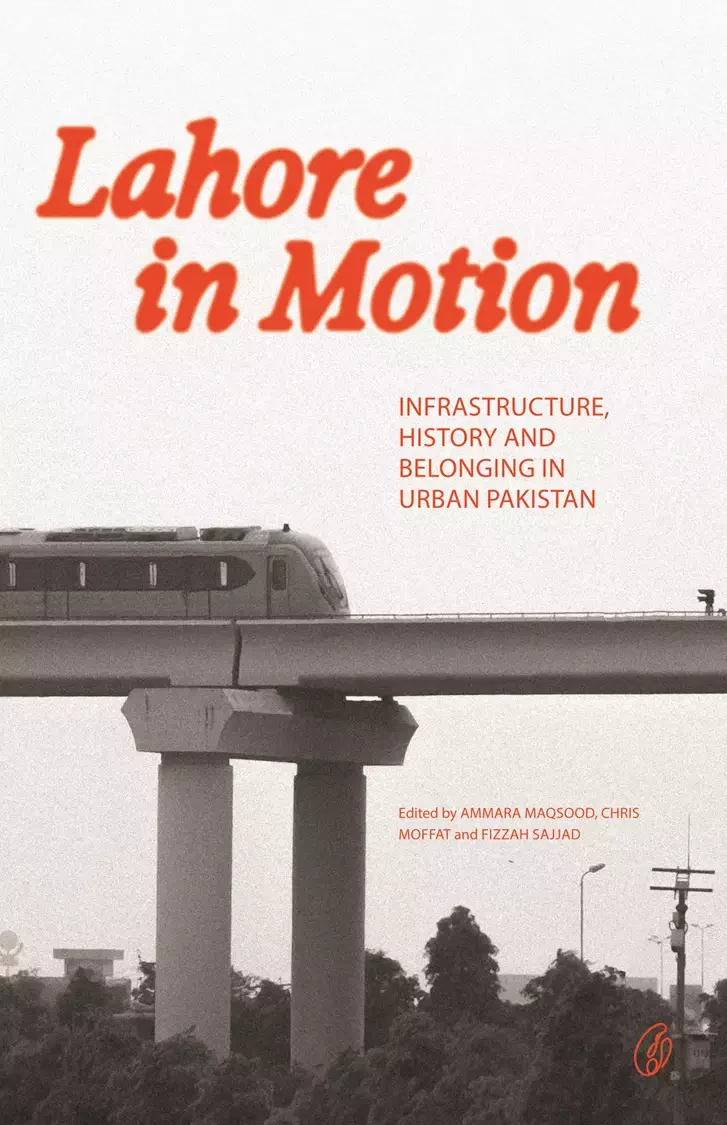

Lahore in Motion: Infrastructure, History and Belonging in Urban Pakistan (UCL Press, 2025), edited by Ammara Maqsood, Chris Moffat and Fizzah Sajjad, is an ambitious anthology of 26 essays, each dedicated to one stop of the Orange Line Metro. It is an attempt to help make sense of this feeling. I first heard of it earlier in 2025 via the UCL Press that published an electronic version of the book on its site for all to access. A few months later, I found myself on a walking tour organised by the people behind the book, as part of an off-site activity of the Indus Conclave 2025. A small, motley group of urban design and planning enthusiasts gathered together on 5th October at Alhamra to set out for the tour.

The walking tour was short, in hindsight, but engaging with the spaces that cradle an important section of the Orange Line enabled this scribe to identify and understand the questions of belonging, nostalgia and history that naturally arise in the event of infrastructural development in post-colonial cities such as Lahore.

Such questions and investigations are at the heart of Lahore in Motion. Its various contributors all attempt to navigate pre-existing narrow, static notions of how Lahoris should and should not react to the Orange Line. They also serve as locksmiths, giving you entry into portals of the city that have historically not been given coverage in contemporary literature on Lahore. This attempt has led to the uncovering of rich narratives — all distinct in their voice, but with a singular thematic overlap serving as its undercurrent.

Opening with Chris Moffat’s essay on Dera Gujran — the first stop on the Orange Line — we are led, tour-guide style, down a semi-urban area that comfortably assumes an ‘in-between’ category. Neither city nor village, but a third, secret thing. The essay provides insight into why and where so much of the city sources its much-beloved bricks from, without which much of the classic character of many of Lahore’s famous buildings would cease to exist. That the inaugural stop on the Orange Line is also elevated at a relatively higher position to accommodate both the Ring Road and GT Road is another of the author’s observations; a reminder of the many ways in which Pakistani bureaucracy serves as both facilitator and opposition to a smooth, soft transitioning of the city’s jump into the future.

Lahore in Motion’s various contributors all attempt to navigate pre-existing narrow, static notions of how Lahoris should and should not react to the Orange Line. They also serve as locksmiths, giving you entry into portals of the city that have historically not been given coverage in contemporary literature on Lahore.

This was a recurring point of conversation during the walking tour, in which participants were urged to explore one section of the Orange Line metro station on foot, to examine and critically think of the multiple ways in which it both engaged and created a rupture with the world immediately outside its environs. In a way, much like the book itself, the tour was an exercise in thinking about the Orange Line’s place in Lahore. Did its addition in the daily lives of Lahore’s citizens make sense or was it an imposition on the city’s delicately layered ecosystem? Both the book and the walk made me ponder over the politics of power and belonging — who gets to decide what belongs and doesn't belong in Lahore, anyway?

Before boarding the Orange Line at the GPO station, Fizzah Sajjad, one of the editors of the book and tour guides of the day, warned us against pedestalising the train (pun very much intended). Instead, she nudged participants to critically see the station’s exterior. One moment, in particular, stands out the most in my memory. It’s when it dawned on all the participants that, in the event that someone completely new to the area arrived at that junction for the express purpose of boarding the Orange train from the GPO station, it would have been very likely that they’d never make it inside. That is because, as Sajjad deftly pointed out, there was no way to tell that the unimposing structure which sits on the intersection of McLeod Road and Mall Road is indeed an entrance to one of the only two underground metro stations in the entire 27-km long Orange Line.

No signboards existed to tell otherwise (I admit I have not been able to go back and check if this has changed since then).

Some labelled this as emblematic of the lazy turgidity that is typical of Pakistani bureaucracy; the psychologist in me wondered if it alluded to a subconscious thought-processing mechanism that informed the city-planner’s cognition, in particularly how s/he viewed mass transit projects, such as the Orange Line, as gestures of benevolence for the city’s middle class.

Once inside, participants were again requested to notice everything with a critical lens: from the ways in which the station’s sterile interiority contrasted with the ruggedness of the world outside to how the regular commuters’ behaviour may have differed from us, the casual, curious onlookers ‘checking out’ the Orange train. One thing that I keep going back to when I think of this part of the tour was the absence of the classic sounds that pervade Lahore’s atmosphere: pigeons cooing, cars honking, children screeching. I wonder if this is seen as a marker of ‘development’.

Contributors to Lahore in Motion have all tried to answer similar questions: what opportunities arise, and fall, with the advent of intra-city connectivity? Shandana Waheed, in her essay on Islam Bagh, sees it as an opportunity for ‘counter-mapping’, to be able to give new meanings to heritage. This is also apparent in many other contributors’ works, such as that of Faizan Ahmad’s chapter on Pakistan Mint that helps us see a rare inside-picture into the daily lives of people living inside the country’s only coin-making entity. Bibi Hajra’s pictorial essay on the Canal View stop, too, talks of the newfound ways of connection that residents of her previously insular world in Canal View Housing society have found with the incorporation of the Orange Line in their vicinity.

One thing that I keep going back to when I think of this part of the tour was the absence of the classic sounds that pervade Lahore’s atmosphere: pigeons cooing, cars honking, children screeching. I wonder if this is seen as a marker of ‘development’.

Other contributors, however, can be seen toggling between their initial rejection and subsequent (begrudging) acceptance of the Orange Line’s positionality as a mainstay in the Lahori experience. Mina Malik, responding to the Ali Town stop, fondly remembers the good old days of her childhood in the city when it was a quiet oasis-town, untouched by the ‘development’ that would soon follow, first in the shape of road expansions and new underpasses on the canal, and then, eventually, by metro-stations and train-tracks. Aimen Jaffer, also struggles with ambivalent feelings towards the evolution of the city’s identity in an essay on Lakshmi Chowk.

Editors of the book have thus appositely approached the city as a “forum of frictions”. Each contributor, in their own way, tries to balance their natural desire to give in to nostalgia and lament about Lahore’s pre-Orange Line past with an equally brave attempt at cautious optimism for the city’s future. Some are better at striking this balance than others. To this reader, what becomes most apparent in the end is that Lahore, like any mega-city in post-colonial states of the Global South, is going to keep transitioning. Many writers reference it as a palimpsest in this anthology, and that is exactly how I came to see it by the end of the book. Lahore in Motion is a brilliant, tapestried attempt at striking a balance between a seesaw of nostalgia and dignified acceptance of the city’s ever-changing landscape. How one engages with it depends entirely on which side of this seesaw they find themselves on.