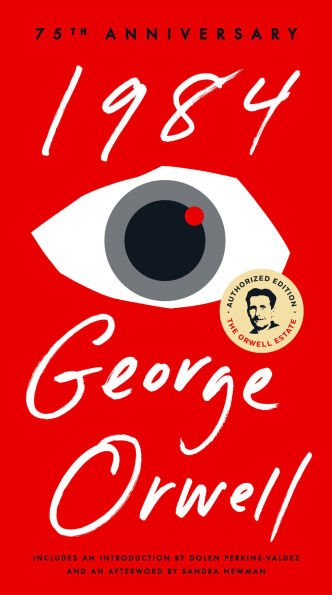

When I first read George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four in my early teens, I remember being put off by its one-dimensional characters and its dark suffocating atmosphere. There was also a distinctly prurient touch that I found disorienting in what is widely considered a work of literature. Most of it went over my head, of course, it wasn’t my type of book at all. But even then I had a vague sense that this was one of those cult classics which would always appeal to a small nihilistic clique.

A close association for me was Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner movie from 1982, with its dark decaying cyberpunk vibe and warped and defeated characters that I found impossible to connect with. In the classic dystopia category, I definitely preferred Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, where at least one character was sane and human.

But now, picking up 1984 as an adult—a working professional, a parent, an educator and a citizen—the book is a revelation. It is absolutely terrifying, more so than most dystopias put together, like a hair-raising trek through Dante’s Inferno.

Could it be because this nightmarish vision seems a lot closer today? Orwell might smile if he were to see the new trigger warnings accompanying the 75th anniversary edition of his book, but, one could very easily argue that Brave New World got more things right about the future than 1984 did.

No, it’s likely because 1984 lays bare the totalitarian impulse, in all its naked hellish glory, in a way that no other book does. One can only appreciate it with age. Orwell himself approved of Brave New World when he read it, but he had one comment about it which cut right to the heart of things: “There is no power-hunger, no sadism, no hardness of any kind.”

Huxley’s prophesied bread and circuses, a society content to anesthetise itself into oblivion. Orwell’s vision is that of mass surveillance and shock troopers, unimaginable physical and mental torment and a reality constantly in flux. Huxley is intellectual where Orwell is visceral. “If you want a picture of the future,” says O’Brien, the antagonist in 1984, “Imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

1984 lays bare the totalitarian impulse, in all its naked hellish glory, in a way that no other book does. One can only appreciate it with age.

This obscene and violent image, this need to utterly absolutely dominate, rears its head often in history. The most immediate reference is the viral photo of a US police officer pinning down an African-American man, George Floyd, that sparked the 2020 riots and a renewed Black Lives Matter movement in America. It harks back to the American Revolution’s famous ‘Don’t tread on me!’ rallying call two and a half centuries ago. We find it often in the last century, in photos from the notorious gulags of the USSR and the killing fields of Cambodia. It is the same road that winds its way from Nanjing and Auschwitz to Gaza today.

Michael Jackson captured the pulse of this drive when he recorded They Don’t Really Care About Us. We witnessed it in spades in the ‘War on Terror’—it’s hard to come up with a more Orwellian name than that—ranging from the CIA’s ‘enhanced interrogation’ protocols to Obama’s ‘kill’ lists, the mentality of drone warfare and the depravity of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. The detention of Julian Assange recalls Winston Smith’s torment in 1984.

And, on a less grim note, we have Big Brother: the omnipresent watchful face of totalitarianism in 1984 inspiring a reality TV show running for over 20 years now in multiple countries and close to clocking a thousand episodes.

The Psychology of Tyranny

In 1984, the world has been split into three superstates: Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia. All are locked in a state of perpetual conflict. Our protagonist, Winston Smith, lives in London, the capital of Oceania, where he works for The Party, the totalitarian political organisation which rules Oceania. English Socialism (IngSoc) is the dominant political ideology.

Society is highly regimented: the Inner Party, comprising the ruling elite, lives in relative luxury. Winston belongs to the Outer Party, the middle class with bureaucrats, technicians and professionals. Then there is the Proletariat—the proles—the labourers, factory workers and the unwashed masses at large, kept in a state of distraction by cheap entertainment, pornography and lotteries. At the very top of the pyramid is the quasi-omnipotent deity Big Brother, the loving protector smiling down on everyone.

People lead a dull vapid insect-like existence in dirty shabby houses. There is no art, beauty or laughter. A constant tension exists between the state and the individual. A secret police force, the Thought Police, monitors the population for thoughtcrime, i.e. any sentiments or activities unapproved by the party. A ‘telescreen’ is installed on every wall, a dual television/camera device that surveils and propagandises to citizens at the same time.

Loyalty rituals have been instituted. In the daily Two Minutes Hate, people gather at workplaces to rage and rant and scream at videos of state enemies. War prisoners are publicly hanged. Schools teach young children to spy and report on their parents. Language itself has been twisted inside out to control human thought. Big Brother is not satisfied with unquestioning obedience— he demands complete mental control.

“The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.”

Winston works in the Ministry of Truth where his job is to constantly revise history to align with current narratives. Here he encounters Julia, a free spirited girl, also a rebel against the status quo, with whom he embarks on a clandestine and passionate affair, setting off a sequence of events that lay bare the intricate and twisted logic on which society operates. (The character inspired an eponymously titled novel by Sandra Newman and published in 2023—arguably, one of the best companion pieces to 1984, as it takes us through Oceania through the eyes of Winston’s lover. Newman notably wrote the afterword for 1984’s 75th anniversary edition.)

Oceania is colourless and drab, sweaty and dusty. The food has no flavour. Everything smells of something. The only consolation Winston finds is in an old glass paperweight with a pretty fragment of coral in it, a relic from a bygone age. He seems to find more solace in that than he does in Julia’s arms. This glass marvel is emblematic of everything precious in life—it is fitting that it is the very first thing the Thought Police destroy when they come for him.

The writing is clumsy in places—Orwell is clearly more of a thinker, an intellectual, than a writer—but he has a vision, a revelation to communicate and it bursts forth. Oceania is immediate, it is stunning in its intensity. It makes the skin crawl. Oceania is the real star of the show, Winston’s job is to walk us through it. One could easily quote here a reviewer commenting on writer Frank Herbert and his masterwork Dune: “The time lives. It breathes, it speaks, and [he] has smelt it in his nostrils.”

1984 also had its share of critics. Milan Kundera, for instance, found the scenes and characters “as flat as a poster”, the book itself an injustice to the novel form, because of its “implacable reduction of a reality to its political dimension alone”; he believed 1984 itself “joins in the totalitarian spirit, the spirit of propaganda”. This is a valid point, even if slightly exaggerated.

Today, as governments around the world shed their democratic pretensions, George Orwell helps us conceptualise what lies ahead: 1984 provides us with a framework and a vocabulary, a way to make sense of this reality. It is a cultural blueprint. Arguably the cultural blueprint.

Tenor of the Times

The casual reader must be warned though: a deep dive into 1984 and one is likely to resurface charged with a whole host of questions, a new vantage point to look at reality.

And what could be more real than our reality?

Pakistan is a living breathing dystopia in its own right, beset with Herculean crises. Floods ravaged the heartland again this summer and now, Punjab is again feared to be the global epicenter for smog. Every summer, we can expect record-breaking heat waves and freak cloudbursts. The worst political crisis in decades continues to drag on at a soul-crushing snail’s pace. Inflation cuts deep into the honest man’s pocket. Emigration is at record high.

Totalitarianism takes on a crude form in developing countries like ours, the stock template of the Communist regimes of the last century. Politics tends to be largely manufactured. Journalists are bought and paid for. There are night-time abductions and speedy show trials, prisoners-of-conscience and occasional assassinations. The propaganda is cloying, heavy and thick—sometimes even comical.

And this is why 1984 is important. Today, as governments around the world shed their democratic pretensions, George Orwell helps us conceptualise what lies ahead: 1984 provides us with a framework and a vocabulary, a way to make sense of this reality. It is a cultural blueprint. Arguably the cultural blueprint.

By and large, the verdict is in. In a public poll conducted in 2007 by The Guardian’s Books section, the public voted overwhelmingly (22% of the vote!) to declare 1984 the ‘definitive’ book of the 20th century.

So as 1984 turns 75 years old, let us take this as an opportunity to pick it up again. (There’s also an Urdu translation, Unees So Chorasi!) Let us revisit Oceania, let us wrestle with Big Brother anew, let us try again to make sense of our deeply troubled times. And let us take to heart Orwell’s own words: “The moral to be drawn from this dangerous nightmare situation is a simple one. Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.”