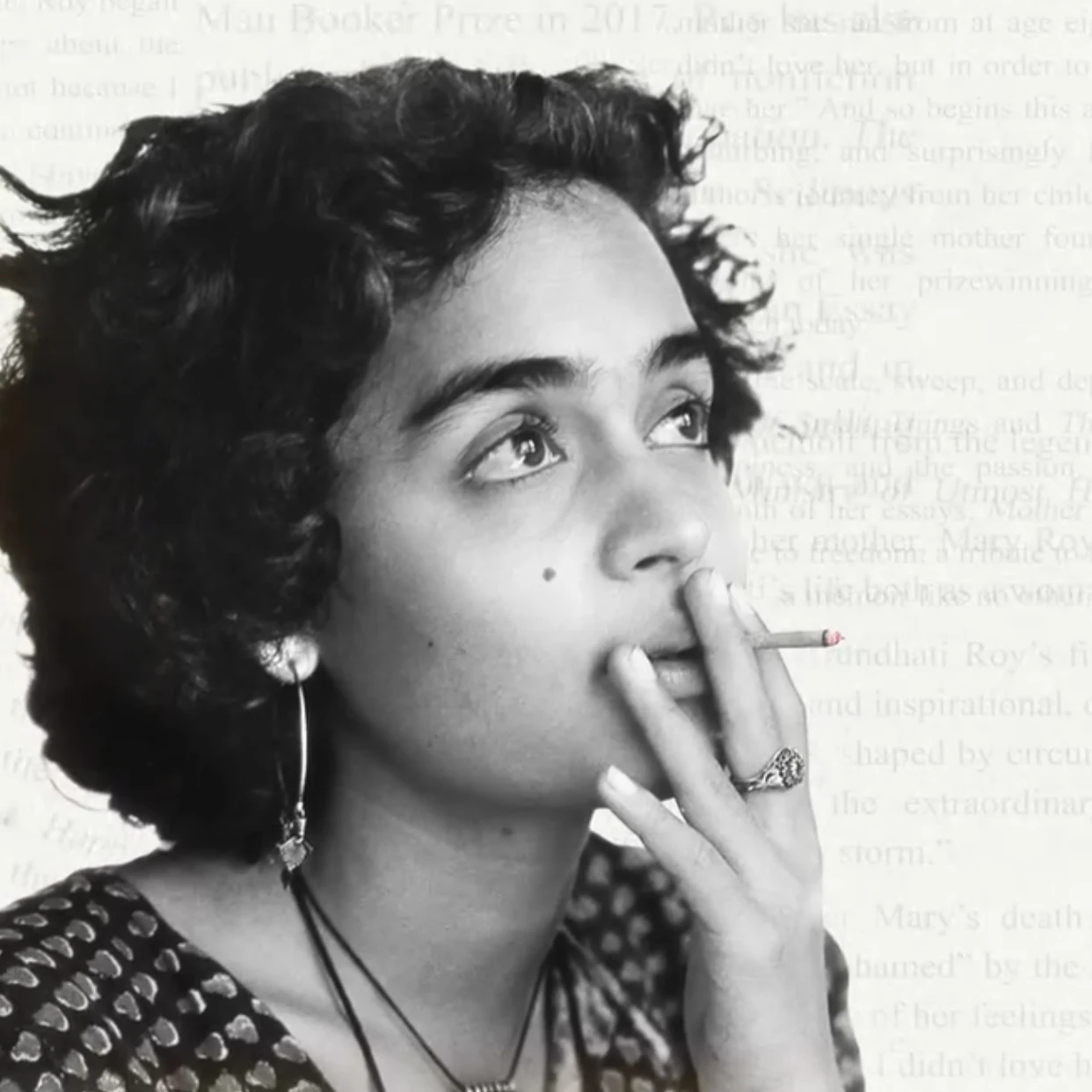

If I had a penny for each memoir I’ve recently read where the author has a complicated relationship with her mother — and publishes said memoir after the mother’s death — I’d have threepence. It’s a certified, card-carrying literary subgenre at this point. For instance there’s Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart, a lyrical ode to grief filtered through kimchi and Korean identity; there’s also Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, brutalist architecture in book form laying bare the horrors of abuse, with a title that acts as blunt-force trauma. And now, there is Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy.

This third penny feels different. Heavier. Minted from another kind of metal.

Mother Mary Comes to Me really resonated with me — and I suspect it will for anyone who has lived with Roy’s work rattling around in their soul for the last twenty five years. Arundhati Roy has played such a central, almost foundational, role in my own relationship with literature, with her groundbreaking work, The God of Small Things. Most readers I talk to have their own story with that book: where they were when they read it, how it split their world open, how it affected them on a deep, molecular level with its backwards-running timeline, its intoxicating lyricism, and its absolutely heart-rending story.

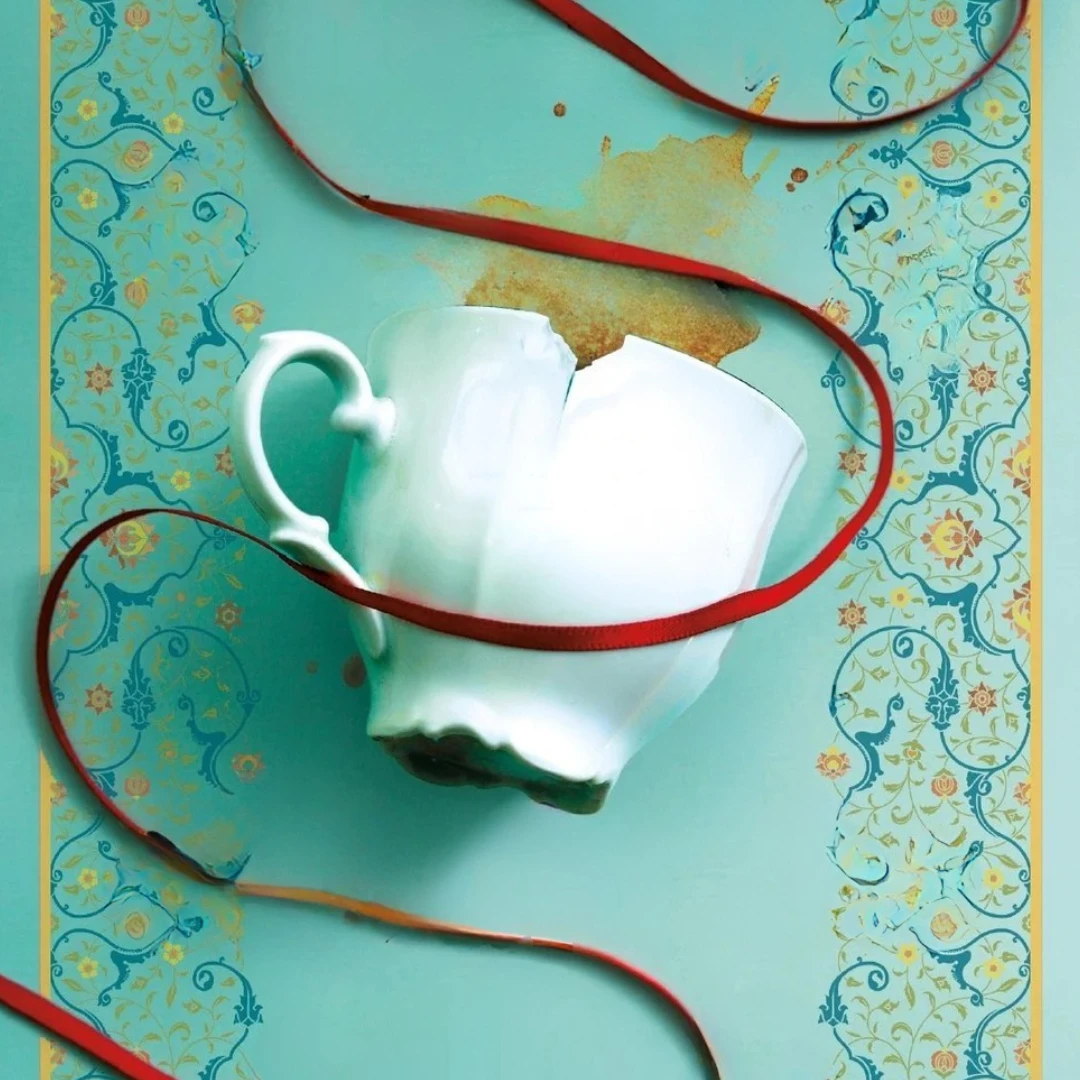

Reading Mother Mary is like re-reading The God of Small Things with a new, intensely painful set of prescription glasses. The memoir acts as a non-fiction companion, a parallel text that illuminates the dark corners of the novel. The fraught, tender, and terrifying relationship between Rahel and Ammu in the novel is cast in stark, new light.

So, when Arundhati Roy, the elusive, controversial, yet trailblazing figure who pivoted from literary superstardom to full-time political activism, decides to write a memoir about her mother, the world snaps to attention. And let’s be clear. This isn’t just any mother. This is Mary Roy — a towering, formidable individual in her own right — an educator and activist who successfully challenged Indian inheritance law. This goes beyond a run-of-the-mill mother-daughter story and shows how Roy, the daughter, was forged in fire by an even more indomitable mother.

The primary draw though, the thing that will have The God of Small Things devotees flocking to this book, is the promise of a key; a decoder ring. With numerous references to the novel in it, the memoir shows how deeply autobiographical her debut work of fiction truly was.

And oh, how autobiographical it was!

Reading Mother Mary is like re-reading The God of Small Things with a new, intensely painful set of prescription glasses. The memoir acts as a non-fiction companion, a parallel text that illuminates the dark corners of the novel. The fraught, tender, and terrifying relationship between Rahel and Ammu in the novel is cast in stark, new light. Here, we see the source of Ammu’s mercurial nature: the real-life Mary Roy, a woman who, like Ammu, was a rebel, a force of nature who loved her children but was perhaps too wild and wounded to be a ‘soft’ mother in the conventional sense.

Roy writes of her mother with a devastating combination of awe, frustration and a deep, unshakeable love that seems to exist separate from affection. She details the inheritance fight, the social ostracisation, the crushing weight of convention in Kerala that she and her mother both railed against, albeit in different, often conflicting, ways. The memoir confirms what many suspected. The God of Small Things wasn't just fiction; it was an exorcism. It was Roy taking the Big Things of her childhood, i.e, trauma, caste, class and a broken-hearted mother, and making them Small enough to be contained, examined, and perhaps, survived. Mother Mary Comes to Me is the story of how those Big Things got there in the first place.

But what really stands out about the book, beyond the Small Things connection, is how intimate it is. This is the second promise of the memoir and Roy delivers on it with an almost painful vulnerability. If her essays are razor-sharp attacks on the state, this memoir is that same blade turned inwards. Roy gives a raw, unapologetic perspective on her life and the fraught relationships she went through, whether familial or romantic.

She is famously a private person. Her pivot to activism was, in part, a way to deflect the intense personal scrutiny that came with the Booker Prize (then Man Booker). Her political writing is passionate, but it's aimed at systems, such as dams, governments, corporations. Here, the lens is squarely on herself.

She lets us in on what she perceives as her own flaws, with the attempt to sabotage her own happiness being a particularly painful one. She writes about her romantic relationships with a bracing honesty, detailing her own culpability in their endings, her fear of being trapped, and her unbearable need for freedom; a need she directly links to the stifling, watchful environment of her childhood. There’s a recurring theme of her running away, not just from places, but from moments of potential contentment, as if happiness itself were a cage.

This self-analysis is the book’s greatest strength. It would be easy for Arundhati Roy to write a memoir that polishes her own myth. The brilliant writer, the righteous activist, the fearless voice for the voiceless. She does not. Instead, she presents a portrait of a woman who is often difficult, profoundly lonely and deeply ambivalent about her own power. She doesn’t ask for absolution; she’s just showing the receipts.

What really stands out about the book is how intimate it is. If her essays are razor-sharp attacks on the state, this memoir is that same blade turned inwards. Roy gives a raw, unapologetic perspective on her life and the fraught relationships she went through, whether familial or romantic.

The title itself, Mother Mary Comes to Me, is a masterstroke of irony. It evokes the beatific, comforting vision of the Virgin Mary, a stark contrast to the complex, fiery and deeply human Mary Roy; it is also a stellar Beatles reference, to boot. The memoir is Roy’s ‘whisper[ing] words of wisdom’, but those words are not ‘let it be’. The words are: ‘fight back’, ‘question everything’ and ‘don’t you dare’.

This is not Crying in H Mart — there is no neat reconciliation through the comfort of food. This is not I’m Glad My Mom Died — there is no clear-cut victim and villain. The relationship here is a tangled, Gordian knot of two brilliant, obstinate, revolutionary women who were, for better or worse, mother and daughter. They were mirrors to each other, and Roy unflinchingly documents how often that reflection was distorted by pain, by society, by their own shared and unshakeable pride.

This memoir is a difficult read, not because the prose is dense (it’s as luminous and precise as ever), but because the emotions are so raw. It is a book about her revered ‘Love Laws’, but in this case, the real-life ones. The ones that dictate whom a daughter should love, and how. And what happens when that daughter, and her mother before her, decide to break them all.

So, yes, it’s a third penny in the jar. But this one... this one feels like that rare penny coin collectors would salivate over. It’s not just a memoir about a complicated mother. It’s the origin story of a voice that shaped a generation, and it's a final, aching look at the woman who lit the fire.