As hard as it may be to believe, Pakistan once had a lot in common with South Korea. In 1962, both Pakistan and South Korea had a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of about USD 100. Both countries emerged from occupation within a year of each other, and both have had to deal with persistent tensions and territorial disputes with neighbouring countries. To this day, both countries also struggle with military interference in government. Yet the economic trajectories of the two nations have been vastly different. Today South Korea’s GNI per capita is well over USD 35,000. Pakistan languishes at USD 1,500.

There has also been a marked divergence in the lives of individual citizens. The average South Korean can expect to live 15 years longer than her Pakistani counterpart. Pakistanis are five times more likely to die of communicable diseases than South Koreans are. While 1 in 5 people in Pakistan is undernourished, in South Korea, the ratio is closer to 1 in 50.

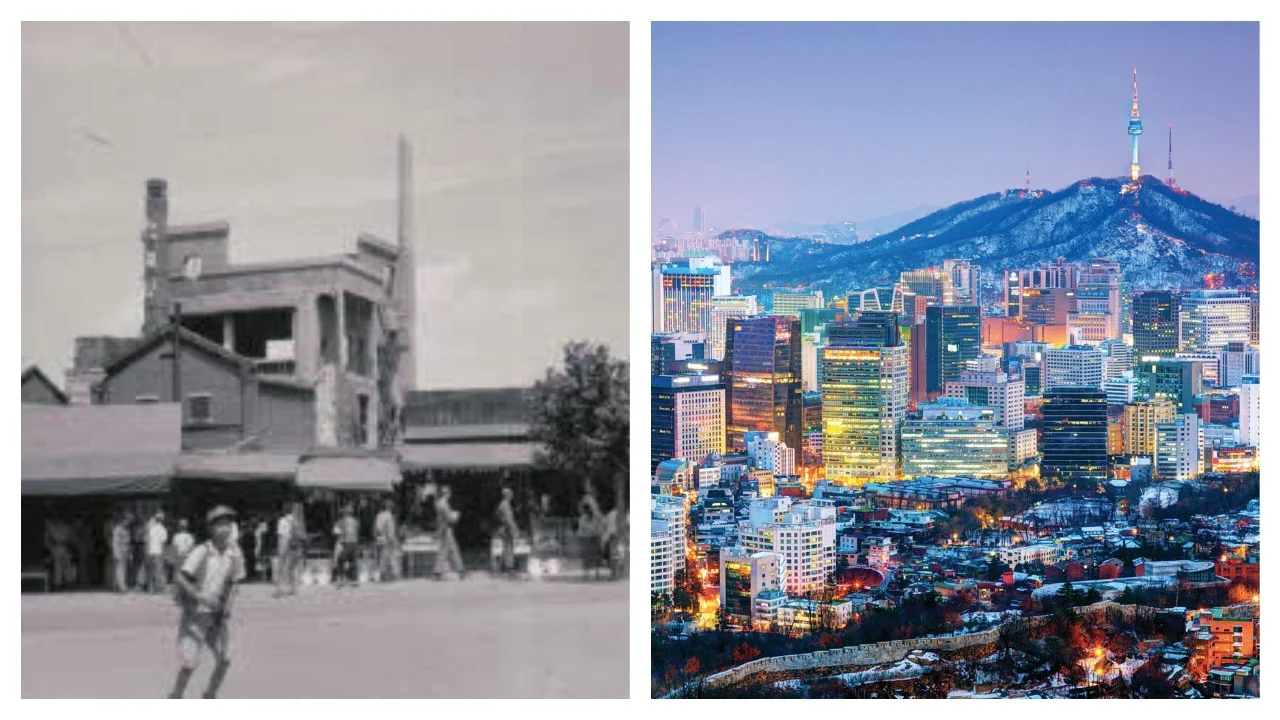

There is no shortage of opinions as to where Pakistan went wrong. And similarly, there are multiple perspectives on the drivers of South Korea’s rapid growth. For Pakistan to attempt to replicate the economic development experience of Korea at this stage may well be a futile effort. Korea’s journey was unique, hailed as the ‘miracle on the Han River’.

Nevertheless, there is much to admire about Korea and much that Pakistan should seek to emulate. But it may not necessarily be Seoul’s gleaming skyscrapers or its chaebols that Pakistan should try to replicate.

Pakistan’s top decision-makers are operating under the assumption that economic growth is the solution to Pakistan’s woes. But it is worth asking, who is it all for?

For Whom the Chaebols Toil

South Korea’s growth-oriented state policies had a clear goal: to enhance national wealth and stature. The state’s orientation was never explicitly towards public welfare and equity in the distribution of wealth and resources. Although Korea managed to avoid deterioration in income inequality during the initial decades of its growth, this was more fortuitous than deliberate.

Quite the contrary, much of government intervention was in support of the wealthy business community in order to maintain export-led growth. Through much of the 70s, government policy repressed wages to maintain export competitiveness. Wages as a share of total value added declined from 36% in 1958, to less than 25% by 1976. After a brief period of wage increases, President Chun Doo-hwan’s government intervened again in the early 80s to keep wage demands at bay to protect exporters. These business conglomerates in turn served as reliable implementers of government policy and sources of political funds, reinforcing the symbiotic relationship.

The rising tide of economic growth did lift all boats, but this was not by design. Government policies disproportionately favoured large scale firms, discriminating against small establishments. Through the 1960s and 70s, firms with more than 100 employees grew at double digit rates — up to 30% annually for the largest conglomerates — while the output growth of smaller businesses languished in the low single figures. In the 1960s, more than half of national income came from independent small businesses. By the 1980s this was down to less than a third. Not only did growth of mega-conglomerates at the expense of small businesses result in concentration of economic power in relatively few hands, it also forced a substantial portion of family establishments out of business and into dependency on wage-oriented labour.

Who Is It All For?

Today, Pakistan’s top decision-makers have numerous advisors telling them what the country should be doing. The International Monetary Fund as usual has advised ‘structural reforms’ to improve tax collection and increase fiscal space for spending on development. Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb has identified climate change and unchecked population growth as the obstacles to Pakistan becoming a USD 3 trillion economy — 50% larger than where South Korea is today. And the Asian Development Bank last quarter highlighted political instability and security as the key risks impeding an accelerated growth trajectory.

Underlying each of these diagnoses is the assumption that economic growth is both the solution to Pakistan’s woes and the end goal it should be pursuing. But it is worth questioning this premise. Specifically, those in charge of running Pakistan need to be asked, who is it all for?

The answer will dictate, to a large degree, whether Pakistan should pursue economic growth itself, as Korea did, or pursue the purported benefits of economic growth, ie., improved education, healthcare, infrastructure and quality of life. The type of state-led, centrally planned economic growth, which Korea followed well into the late 90s, will be far more beneficial to those who already hold the reins of power and capital than to those without opportunities and resources.

If Pakistan’s leadership cadres want to benefit themselves and their associates, then this growth-centric paradigm — involving heavy government support and incentives to already well-established business houses and direct participation in lucrative markets such as real estate, mining and agribusiness — is the way to go. Indeed, this is what has already been happening in Pakistan in different incarnations since the 1950s.

If, by some miracle on the Soan River, Pakistan’s leadership truly intends the beneficiaries of this pursuit of prosperity and wealth creation to be ordinary Pakistani citizens, then a different approach is needed, one that recognises that economic growth is not synonymous with development. The assumption that quality of life improvements naturally emerge as a result of economic growth needs to be revisited.

The Chicken or the Egg

This conflation of growth and development, popularised by the modernisation theory post-World War 2 and subsequently embedded into conventional economic wisdom, frames economic growth as being intrinsically good. In this narrative, economic growth is the engine of progress, enabling countries to move linearly from being poor, underdeveloped nations to becoming wealthy, developed nations that can offer their citizens advanced services, such as public utilities and quality healthcare and education. On the face of it, South Korea’s journey fits this traditional growth and development narrative quite well.

There is indeed a correlation between improving public services and quality of life and economic growth. But correlation does not imply causation. In fact, the direction of causality may be the other way around, or, at best, bi-directional. In developed countries, well into the Industrial Revolution, the correlation between well-being indicators and per capita GDP (the primary measure of growth) was close to zero. It was not until improved healthcare, nutrition and education helped to increase worker productivity that GDP started to move in tandem with, and in a positive feedback loop with, well-being indicators.

Korea’s own history bears this out. One of the reasons that Korea’s economic growth resulted in a relatively equitable distribution of gains in initial years was because of land reforms and investments in education during the 1950s, before the government began focusing purely on growth. The literacy rate grew from 30% in 1953 to 80% within ten years, paving the way for industrial growth.

A Direct Approach

Irrespective of whether Pakistan’s government wants to achieve growth for the sake of growth or growth for the betterment of its population, the path forward is relatively clear. Pakistan should be investing in human capital and social infrastructure first and foremost. This is what sets the foundation for development of the economy, and this is the lesson to learn from Korea. From 1962 to 1980, even with manufacturing as a national priority, Korean government spending on infrastructure and social overhead averaged well-above 60% of total public sector investment. Pakistan should pay heed. Investments in rare earth metal mining and artificial intelligence ventures are pointless if there are not enough engineers to do the work.

Pakistan first needs to invest in the physical and intellectual infrastructure that will enable and sustain a vibrant and growing economy. Technical colleges and tertiary educational institutes will not churn out high quality workers if educational foundations at the primary and secondary level are weak. Workers cannot be productive if they are worried about the cost of food and medical care or are struggling to commute to work. Basic necessities and health coverage need to be affordable, or made accessible through targeted cash transfers. Public transportation systems need to be exponentially expanded to enable easier movement between where people live and where they work. Good transportation can enable people to live in more affordable, sub-urban areas without impairing their access to employment opportunities.

Unless individuals’ lives are made better, Pakistan cannot sustainably grow. There is no way to unlock the country’s potential when its population is living with their hands tied.

These kinds of investments will do far more to catalyse economic development in Pakistan than any kind of government-led, centrally planned initiatives, because they will directly improve the quality of life of Pakistan’s citizens. Unless individuals’ lives are made better, Pakistan cannot sustainably grow. There is no way to unlock the country’s potential when its population is living with their hands tied.

The Right Kind of Growth

Investing directly in making peoples’ lives better may obviate the need for massive economic growth. This is because economic growth, especially of the variety seen across the capitalist world — where society is oriented almost exclusively around the concepts of economic returns and productivity — actually tends to be the enemy of human quality of life. In fact, poverty, which economic growth is ostensibly intended to counter, is often the direct outcome of efforts to increase productivity and grow economic output.

In Korea, rapid, government-driven industrialisation, particularly in the chemicals and heavy industries sectors, resulted in large amounts of pollution and significant deterioration in the environment. Industrial smog adversely impacted huge swathes of agricultural land, reducing cultivable land to a sixth of pre-industrial levels in some areas, driving thousands of farmers out from tilling their own land to having to work for wages. Rapid, one-dimensional economic growth also had other negative consequences. The population as a whole saw spikes in adverse health conditions, occupational diseases and respiratory illnesses.

Pakistan, already grappling with its own pollution crisis, can learn from this and refocus on the right kind of growth. This will be possible if Pakistan’s economic incentives are structured to promote growth in socially productive and beneficial areas — such as housing, nutrition, healthcare and education. In parallel, legal systems need to be designed not to shield those who are powerful, but to protect those at risk of exploitation and abuse.

Perhaps Pakistan’s miracle can be carving out an alternative path, where our streets are lined with shade giving trees, where communities live harmoniously with nature, and where we safeguard the resources that belong to the commons.

Growth is one part of the solution for Pakistan, but the government's goal has to be improving the lives of individual Pakistanis. Economic gains need to be distributed fairly and equitably so that living standards improve equally for everyone. The adverse consequences of economic growth, such as pollution and waste, destruction of wildlife ecosystems and environmental degradation need to be aggressively controlled and curtailed, because these set back hard-won gains in living conditions.

Perhaps Pakistan’s miracle can be carving out an alternative path, where instead of high rises made of glass and steel, our streets are lined with shade giving trees; where instead of vertically integrated corporations we have integrated communities of people living harmoniously with nature and wildlife; and where instead of depriving the rights of many for the dubious privilege of paying for bottled water, we safeguard and share the resources that belong to the commons.

It should not be too hard to believe that such a Pakistan could be far better off than Korea.