Almost a month ago, just as Lahore began careening toward another smoggy winter, the Indus Conclave (a project of the Punjab Group) arrived with its second iteration. Taking place from 3–5 October at the Alhamra Arts Council (Mall Road), the event was much-needed intellectual rejuvenation from the stagnation of Lahore’s cultural drought.

The weekend began with an art exhibition, ‘A Gentle Apocalypse’, curated by Saher Sohail, and featured the work of 14 artists who attempted to untangle the term ‘progress’ from its western connotations in their own ways. Each of them took upon the task to reimagine modernity as an ‘un-west’ concept, all while emphasising the debris and destruction left in the wake of chasing an ever-evasive ideal of ‘development’.

Walking around the repurposed space outside of Hall 1, where the exhibition was held, I was immediately drawn to Malcolm Hutcheson’s photographic recollection of Mughalpura; people going about their everyday lives, immortalised by a flash from a camera made in Sheikhupura.

There was a slight sense of despair as I observed Faraz Aamer Khan’s ‘Under Raag Kedar’ and learnt of all the colours that we have lost to colonisation. It was a beautiful visual translation of ‘raag’ (a symphony of notes) and a subtle foreshadowing of the events to follow. In the same vein, Amra Khan’s piece — a wooden altar, built from leftover wood from demolished homes and filled with homegrown herbs — served as a poignant reminder that everything we need comes from within us. It was a commentary on how consumerism has repackaged these everyday herbs to sell them back to us under the garb of ‘wellness’. Right next to it was Zohra Rahman’s series of works depicting avian constellations entitled ‘Skyfall’ — an unsettling memento of migrations past and present, and a subtle metaphor for the ideological journey back to ourselves, catalysed by the Indus Conclave.

This soft reckoning was followed by a transcendental evening, where delegates experienced the two things Lahoris love the most, food and song. The raag we only saw before in Faraz Aamer Khan’s work was offered to us in its original form, performed by the legendary Fareed Ayaz. Delegate Eddin Khoo (writer, poet and translator) recalled later that the qawwali evoked a deep sense of ancestral nostalgia within him. Under the waxing gibbous moon, curtained by a canopy of ficus and palm trees, the whole performance was a masterful flirtation between discipline and abandon, setting the tone for the events of the next two days.

Saturday began with an important discussion on ‘Access to Justice in Pakistan’. At a time when the country’s judicial infrastructure wavers under the weight of delayed and denied verdicts, this discourse drew in a demographically diverse crowd as the panellists led the conversation on how the scales of justice can be recalibrated. One audience member, a former lawyer, remarked, “In Pakistan, where justice is a privilege reserved for the well-connected few, conversations like these are all the more important.”

At a time when the world seems to be cannibalising itself, the Indus Conclave provided an immersive, multifaceted experience to collate thought, divulge in discourse and explore the root cause for this self-destructive hunger.

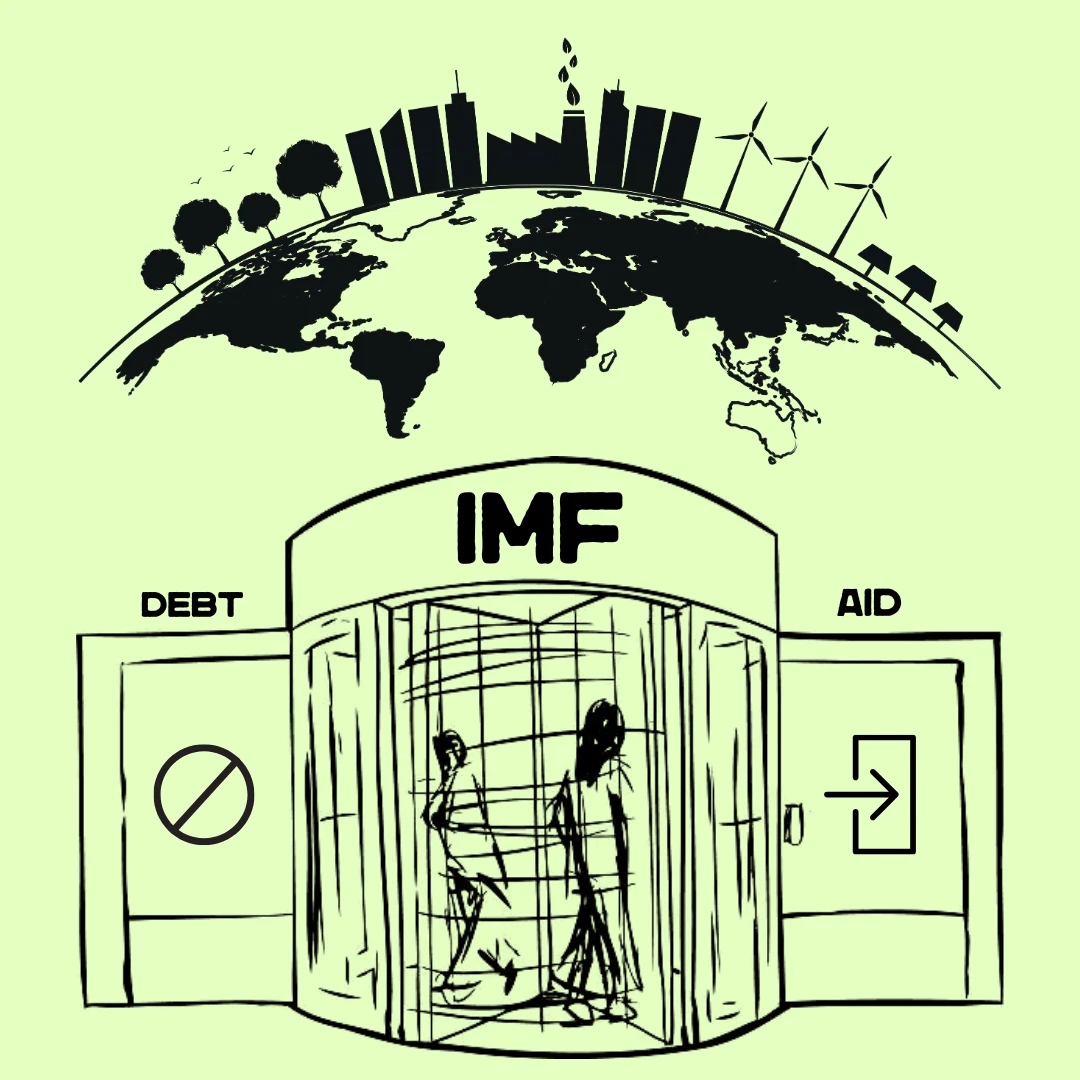

This was followed by a roundtable discussion: ‘What is Pakistan’s Way out of its Growth Trap?’, where the very notion of a ‘government’ and ‘state’ was called into question. Dr Faisal Bari insisted that a functional government can only exist with the involvement of its citizens, which was countered by his fellow panellists, who stated that it shouldn’t be the citizens’ job to ensure the government is doing what it was created to do. The panellists did agree, though, that Pakistan gives a great ‘illusion of growth’ with a new bridge or underpass being constructed at every turn, highlighting that not a single public hospital was built in the last 29 years. I found Dawar Butt quoting an audience member quite illuminating: “development isn’t the goal, development is simply the means to a goal.” For Pakistan that goal remains glaringly undefined, which is perhaps why even with all the new underpasses and flyovers, we keep going around in circles.

Stepping out of the halls, I was immediately enveloped in a melodious soundscape, which lifted my spirits after the heavy conversations of the morning. By this time (early afternoon), Alhamra’s gardens had begun to fill up. An older woman sang the folk ballad ‘Heer’ at the open mic, while a group of students performed an impromptu qawwali on the steps of Hall 2, tablas, harmonium, and all. Any lingering afterthoughts about Pakistan’s unresolved fate were long gone as I sauntered through the courtyard, which had been transformed into a book bazaar. From well-established publication houses like Readings and The Last Word, to Lahore’s very own The Peepul Press, it was Alhamra’s little Garden of Eden.

Later that day, I found myself at ‘Hard Materials - Soft Power: Pakistan and a Pavilion in Venice’, an insightful exploration of the idea, conception and execution of (Fr)Agile Systems, Pakistan’s exhibit at the Venice Biennale. The panellists talked about their decision to use material from the Khewra Salt Mines as the building blocks for their pavilion stating that all materials used reflected the land which they came from. Once placed in an unfamiliar environment, the salt from Khewra began to take new shape and form, as the familiar became foreign. The central focus of the pavilion was on balanced instability with heavier materials strategically placed over lighter ones and suspended pieces of salt rock scattered sparsely across the spread.

“It was the first time I’ve heard instability described as a design principle, and it somehow makes sense,” said a young architect in attendance. The multidisciplinary team noted that this uneasy equilibrium mirrors Pakistan and the wider Global South, speaking to climate inequity and the brunt of Western consumption borne by the South, turning (Fr)Agile Systems into an introspective space.

This was followed by a mouth-watering deep dive into three distinct, yet interlinked culinary worlds: Jordanian, Ghanaian and Pakistani, with Pakistani chef Asad Monga leading the discussion with important questions ranging from: “what’s your signature dish?” to “why are farmers so ruthlessly de-platformed and disconnected from the fruits of their labour?”. When Lydia Amenyaglo (Ghanian food practitioner) spoke about how fermentation of corn is a key cultural practice in Ghana, both Nahla Tabbaa (Jordanian artist) and Asad recounted how central fermentation is to their respective cultures too (achaar, yogurt, cheese, etc.). There was a palpable excitement amongst the crowd as the three panellists mused over the similarities within our culinary inheritances. In the face of Western rejection, it seems the Indus Conclave provided fertile breeding ground for some unlikely, yet necessary, alliances.

While Nahla Tabbaa talked about how Jordanian chefs were tailoring recipes to create healthy foods from the limited raw materials the UN is providing to Gaza, in Hall 1 Palestinian professor Mehran Kamrava took to the stage to discuss ‘The Impossibility of Palestine’. In quite a poignant way, this panel came to Lahore just two days before the two-year anniversary of the aggressive genocidal occupation by Israeli forces and the western world finding out about Palestine. Professor Mehran spoke at length about what it means to live under an active occupation and how in such a context the mere act of existing becomes resistance. It was an emotionally charged discussion on the continued despair of the Palestinian people, with the panellist quite accurately stating, “When God is your real estate agent, it is very hard to negotiate over land.”

He also commented on how the Palestinian cause has been blatantly misused by world leaders to further their own agendas, stating that Palestinians have no friends except for each other.

In keeping with its complex and multi-layered nature, after these sombre exchanges, the Conclave led me to Hassan Tahir Latif’s masterful moderation of ‘Documenting Journeys’ — a more light-hearted introspection of how the places we live in or move away from shape and reshape our perspectives. At day’s end, one of the attendees said they felt “intellectually recharged”, while another said that the overlapping sessions made them feel like they had “a day full of scheduling conflicts, where every meeting was as important as the next one”.

After a stormy reset the night before, at midday on a breezy Sunday, Nahla Tabba opened the doors to her dastarkhwan of encounters through Gawal Mandi and Delhi Gate. This was a collaborative production by the participants of her micro-residency facilitated by the Indus Conclave. The exhibit featured traditional foods sourced from the aforementioned areas, as well as visual representations of the sounds of the city depicted by drawings on the dastarkhwan. As you moved through the installation you found each artist’s own contribution: a paan station, a lassi stand, a sensory experience of spices where you got to look, touch, smell and taste as part of your journey. My personal favourite was Muhammad Suleman’s trash installation as a representation of our longstanding littering habit. And true to our nature, observers treated this installation as an interactive art piece, throwing away their empty cups of Shezan mango juice, used napkins and half eaten bits to create a giant pile of trash/art. Amongst the audience members enjoying this exhibit, there was also Alhamra’s very own cat, who strangely enough didn’t disturb any of the food placements and only dipped its face in a giant bowl of laal mirch and somehow remained unscathed. “A typical Lahori cat,” remarked Asad Monga, at an atypical Lahori event.

Tracing my way out of the foodscape I landed at ‘Language as Freedom’, where Mohammed Hanif and Jasir Shehbaz delved into the complexity of being held prisoner by an intangible structure such as language. Mohammed Hanif rightfully pointed out that in our confused post-colonial state, we have internalised the concept of education as an erasure of our own culture and values.

“This is evident in the glaring absence of languages like Punjabi and Urdu being taught in private and elite schools,” Hanif commented. One audience member noted that in order to promote a language, we must converse in the language too and thus sparked an interesting back and forth between the panellist and the audience in Punjabi. It was heartening to see the beginning of a return to ourselves.

In a similar vein, at ‘Margins as Method’ Hajra Karrar and Saira Ansari conversed with Maliha Noorani about navigating art and literary spaces globally, especially as people of colour and ‘non-native English speakers’. Their accounts of bias and microaggressions encountered while working across Asia and the Middle East were a lesson in how Western hegemony sustains echo chambers within parts of the Global South, where success is still measured by Eurocentric standards. Recounting her experience, an attendee told me she’d struggled to get published as a translator because of her ‘spoken English’. She further said, “It is strangely comforting to hear others name the quiet exclusions we all recognise but rarely say aloud.”

This was followed by three consecutive book releases, all by Pakistani authors. The first, ‘A Splintering’ by Dur-E-Aziz Amna, which deals with the oft-ignored issue of class disparity in Pakistan. Next, Arsalan Athar’s self-published ‘40 Days of Mourning’, which is set to the backdrop of Hyderabad’s convoluted journey to Pakistan. And lastly, The Peepul Press’ first publication, Adrian A. Husain’s ‘Knife of the Tide’, which was a soft landing after a tumultuous journey through the Conclave.

His sonnets, read aloud by Shaista S. Sirajuddin, talked of days gone by, days to come and days that felt like nothing. Moderated by Mina Malik, this session felt like a cosy, hearthside conversation with a friend and a cup of chai. The audience consisted of Adrian’s friends, family and patrons of literature. It was heartening to see that even if the world seems to be crumbling around us, things like friendship, love, art and poetry continue to persevere.

One of the attendees said they felt “intellectually recharged”, while another said that the overlapping sessions made them feel like they had “a day full of scheduling conflicts, where every meeting was as important as the next one”.

In one of the earlier sessions, Yassmein Abdal-Mageid had said how her aunt, stuck in war-torn Sudan, would often ask her to send ‘something of joy’. It is hard to describe such a thing, but the Indus Conclave came quite close. Much like its namesake, this event allowed for divergence into multiple streams of conversations that all channelled back to a riverbank of shared ideas and thought. At a time when the world seems to be cannibalising itself, the Indus Conclave provided an immersive, multifaceted experience to collate thought, divulge in discourse and explore the root cause for this self-destructive hunger. It seemed only fitting that this discourse on the decolonisation of art, literature and ideas took place on the first weekend of October, as the city moves from the destruction of the monsoon to the oppression of smog. The conversations that reverberated through the halls of Alhamra seemed to have one central focus: a shift towards reorienting South Asian practices in our literary and art spheres. As I exited the building, with the air much cooler than it had been at the start of the weekend, I felt a palpable energy around me, one that felt like change was in the air. Perhaps this — community, sharing of ideas, cultures and experiences — is how we finally break the ‘illusion’ of growth.

All conversations from the Indus Conclave 2025 are now available to watch on their YouTube channel. All photos courtesy of the Indus Conclave.