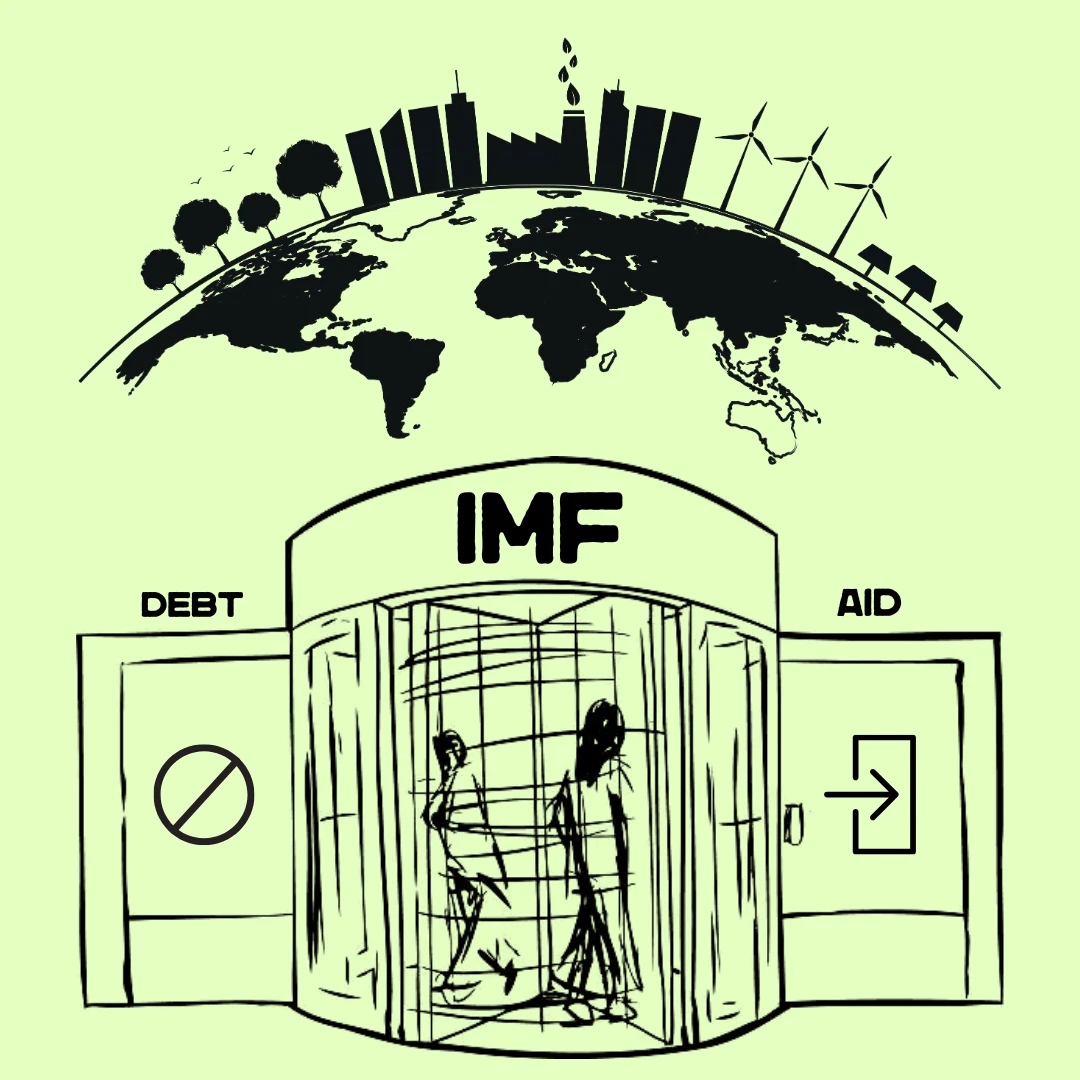

In the hierarchy of global debt distress, Pakistan stands out not for the sheer size of its debt but for the chronic nature of its dependency. The country has turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) twenty-five times since its independence — more than almost any other borrower. This revolving-door relationship has become symptomatic of an economy unable to break free from the twin pressures of unsustainable debt and urgent development needs. Today, with external debt exceeding $130 billion, fiscal space narrowing and climate shocks mounting, Pakistan’s case for innovative instruments such as debt swaps has never been stronger.

At the heart of the crisis lies the structure of Pakistan’s liabilities. As of early 2025, the country’s total external debt stands between $130–$133 billion, of which around $87 billion is public external debt. Servicing these obligations has become suffocating: more than half of Pakistan’s federal revenues are now consumed by interest payments, leaving scant resources for investment in health, education or climate resilience. Unlike larger economies, such as India, that hold diversified reserves and export bases to cushion against shocks, Pakistan’s reserves are shallow, its tax base narrow and its economy highly dependent on short-term borrowing and bilateral rollovers. Each external shock — a commodity price spike, a currency depreciation or a climate disaster — pushes the country back to the IMF’s door.

When set against its regional peers, the depth of Pakistan’s vulnerabilities becomes even clearer. Bangladesh, with a similar income level, has external debt of around $74 billion, just 18 percent of its GDP. Robust garment exports and relatively stable reserves have allowed Dhaka to avoid the revolving-door dependence that plagues Islamabad. Sri Lanka, on the other hand, offers a cautionary tale of what lies ahead if reform is delayed: debt soared to nearly 96 percent of GDP, leading to a sovereign default in 2022 and a painful restructuring under IMF supervision. Pakistan has not defaulted, but its trajectory places it closer to Colombo than to Dhaka.

Pakistan’s problem is not merely the size of its debt; it is the fragility of its financing structure and the narrowness of its economic base, which combine to perpetuate dependence.

The comparison extends beyond South Asia. Among lower-middle-income economies, Pakistan’s record of IMF dependence is striking. Kenya’s debt now hovers around 70 percent of GDP, while Egypt’s exceeds 90 percent, both prompting IMF involvement. Yet neither has approached the twenty five arrangements Pakistan has undertaken. Meanwhile, Vietnam and Indonesia — also classified in the lower-middle-income bracket — maintain healthier debt ratios of 30 to 40 percent of GDP, supported by strong manufacturing exports, foreign investment and more diversified sources of external finance. Nigeria, after rebasing its GDP, reports a lower debt-to-GDP ratio, though it remains vulnerable to oil price volatility. Pakistan’s problem is not merely the size of its debt; it is the fragility of its financing structure and the narrowness of its economic base, which combine to perpetuate dependence.

The consequences of this fiscal constraint are felt most acutely in Pakistan’s development trajectory, which has been repeatedly derailed by climate shocks. The 2022 floods remain the most catastrophic disaster in the country’s history: one-third of the country submerged, damages estimated at more than $30 billion, over 2 million homes destroyed and some 8 million people displaced. Education bore a particularly heavy toll, with more than 27,000 schools damaged or destroyed, pushing children out of classrooms and deepening Pakistan’s already staggering learning crisis where nearly 77 percent of ten-year-olds cannot read a simple text. Health outcomes also suffered, as waterborne diseases surged and rural clinics collapsed under the pressure.

Recent torrential rains in 2025 have reinforced the picture of fragility. Urban flooding paralysed major cities, exposing the absence of resilient infrastructure, while rural areas faced displacement, food insecurity and renewed health crises. These climate shocks strike a country that was already struggling with deep development deficits. Pakistan urgently needs to rebuild climate-resilient infrastructure: from bridges and roads that can withstand floods to housing that can survive storms. Its agriculture sector, the backbone of rural livelihoods, requires adaptation through modern irrigation systems, flood defences and drought-resistant crops.

Yet the irony is stark: even as Pakistan confronts these urgent development imperatives, the fiscal burden of debt servicing leaves little space for action. This is precisely why the discussion around debt swaps is so timely and necessary.

Debt swaps — where part of a country’s external debt is forgiven or restructured in exchange for domestic investment in development priorities — offer a way to transform liabilities into assets. The mechanism is not new; Belize and Seychelles have successfully executed debt-for-nature swaps, channeling resources into marine conservation, while reducing fiscal pressure. Egypt and the Philippines have implemented debt-for-education swaps, funding social investment without worsening debt distress. What these cases demonstrate is that when designed transparently and aligned with global priorities such as climate resilience and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), creditors can be persuaded that such arrangements serve both sides.

Debt swaps — where part of a country’s external debt is forgiven or restructured in exchange for domestic investment in development priorities — offer a way to transform liabilities into assets. For Pakistan, the possibilities are compelling. A debt-for-climate swap could redirect billions of dollars into flood defences, renewable energy projects, and disaster-resilient infrastructure.

For Pakistan, the possibilities are compelling. A debt-for-climate swap could redirect billions of dollars into flood defences, renewable energy projects and disaster-resilient infrastructure. A debt-for-education swap could rebuild thousands of schools lost in the floods and finance digital learning solutions to address learning poverty. A debt-for-health swap could strengthen rural clinics, expand vaccination coverage and prepare for post-disaster disease outbreaks. Each of these swaps would not only address urgent needs but also reduce Pakistan’s long-term vulnerability, making future debt crises less likely.

Critics often argue that debt swaps are too complex or limited in scale to make a difference, yet Pakistan’s situation is exceptional, both in its vulnerability and in the global stakes. As one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world, Pakistan represents a test case for whether international finance can be adapted to the realities of the climate era. Creditors, too, have incentives: redirecting debt relief into visible development outcomes enhances their credibility on climate finance and demonstrates responsiveness to the SDG agenda.

Ultimately, Pakistan’s debt crisis is not simply a fiscal issue — it is a development emergency. Every dollar spent on interest payments is a dollar not spent on a child’s education, a flood-resilient bridge or a renewable energy project that could reduce future vulnerability. IMF bailouts, while essential for stabilising short-term crises, do little to change this calculus. Debt swaps, by contrast, offer a pathway to break the cycle, easing fiscal pressure while directly financing the investments that Pakistan’s people so desperately need.

The choice is no longer between debt relief and development. For Pakistan — and for creditors committed to sustainable finance — the path forward must combine the two. Debt swaps are not a panacea, but in the face of repeated bailouts, deepening poverty and escalating climate shocks, they may represent Pakistan’s best chance to transform crisis into opportunity.