The curtains of the annual play rise. The stage is bathed in a grey haze. A vast dashboard pulses with maps, red lights and shifting data. At the centre of it all stands a female minister, one finger raised in the air as if delivering an important decree. She is flanked by a swarm of aides — mostly suited, booted and acting frenetically. One sprays the air with a watergun, another slaps green stickers on plywood cars billowing smoke, a third man taps nervously at a monitor, its display uncontrollably flickering between a sharp red and an even darker red. Panic.

As the scene intensifies, traffic jams take shape; chimneys belch dark smoke into the sky and fields catch fire in the background. Masks start to rain down like confetti. The minister proclaims, “Clean air. Clean air.”

That moment, the clock on the dashboard adds another year to the timeline, widening the gap between the promise and reality. The minister waves at masked children in school uniforms. She departs. The curtain never quite falls. It simply settles, like dust, leaving the audience to wonder: is this just a tragic replay, or the beginning of something worse?

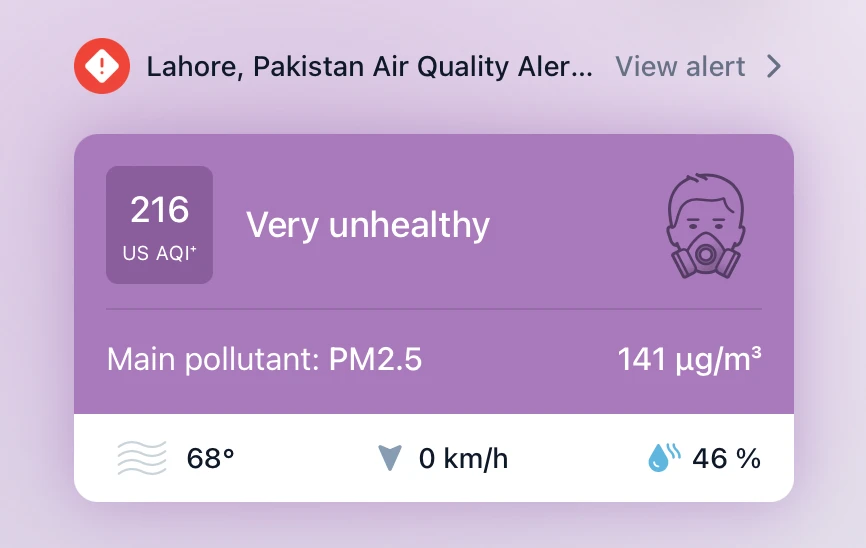

Away from this fantastical scene, in the real Lahore, the proverbial ‘smog season’ is in full swing. The air is ‘very unhealthy’ or maybe ‘hazardous’ to breathe, depending on where you turn for your data collection. Dangerous levels of tiny dust particles are floating in the air, exceeding several times the World Health Organisation’s recommended limit, reducing life expectancy at an average of 3.3 years.

Zainab Naeem, an environmental scientist and policy researcher at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute, explains that smog is the product of a shared Indo-Gangetic airshed plus weather that traps and enhances pollution. She says, “This year's prolonged monsoon spell and floods left moist soils and a humid boundary layer, so fine particles or particulate matter (PM2.5) absorbed water and grew hygroscopically, while SO₂/NOₓ pollutants more readily convert to sulfates and nitrates, both raising measured PM for the same emissions.”

At the same time, cooler nights at the surface, compared to last year, and relatively warmer air a few hundred metres up, created stronger temperature inversions, which lower the mixing height and cap pollutants near the ground, especially overnight and at dawn.

“Post-rain conditions also mean calmer winds and a more stable atmosphere, so day-to-day emissions from transport, industry, brick kilns and residue burning accumulate in place until a ventilation event arrives,” adds Zainab.

Net effect, according to her, is “humidity-driven particle growth + stronger/longer inversions + weak winds in a cross-border basin = earlier, denser smog episodes this season, peaking at night and easing only briefly in the afternoon.”

Lahore now boasts a network of air-quality monitors. Around 12 reference-grade stations and many low-cost sensors have been installed to boost coverage across the city.

Still, this smog season echoes past years. Last year, a smog calamity was declared on Oct 31, 2024. The vulnerable children were sent home from schools on a three month long leave. Burning crop residue, solid waste, tires, rubber and plastic was banned. Smoke spewing motor vehicles were fined. A smog mitigation policy was announced by the Punjab government with a budget of 10.23 billion. The Urban Unit tells us that the average AQI last year in October was 128 and in November was 286.

The year before that in 2023, an anti-smog squad was formed, section 144 was imposed in the Lahore Division to curb crop burning, commercial markets were closed every Wednesday and the LHC ordered the provincial government to declare a smog emergency in Lahore. Smart lockdowns, a reminder from the Covid days, became an order of the season. Eyes itched, coughs and sore throats became common. Then came artificial rain — to settle dust for a day or so. The AQI was 137 in October and 257 in November.

The year before that in 2022, the average AQI was 129 in October and 127 in November, and in 2021 it was 102 and 277 respectively (as per Urban Unit).

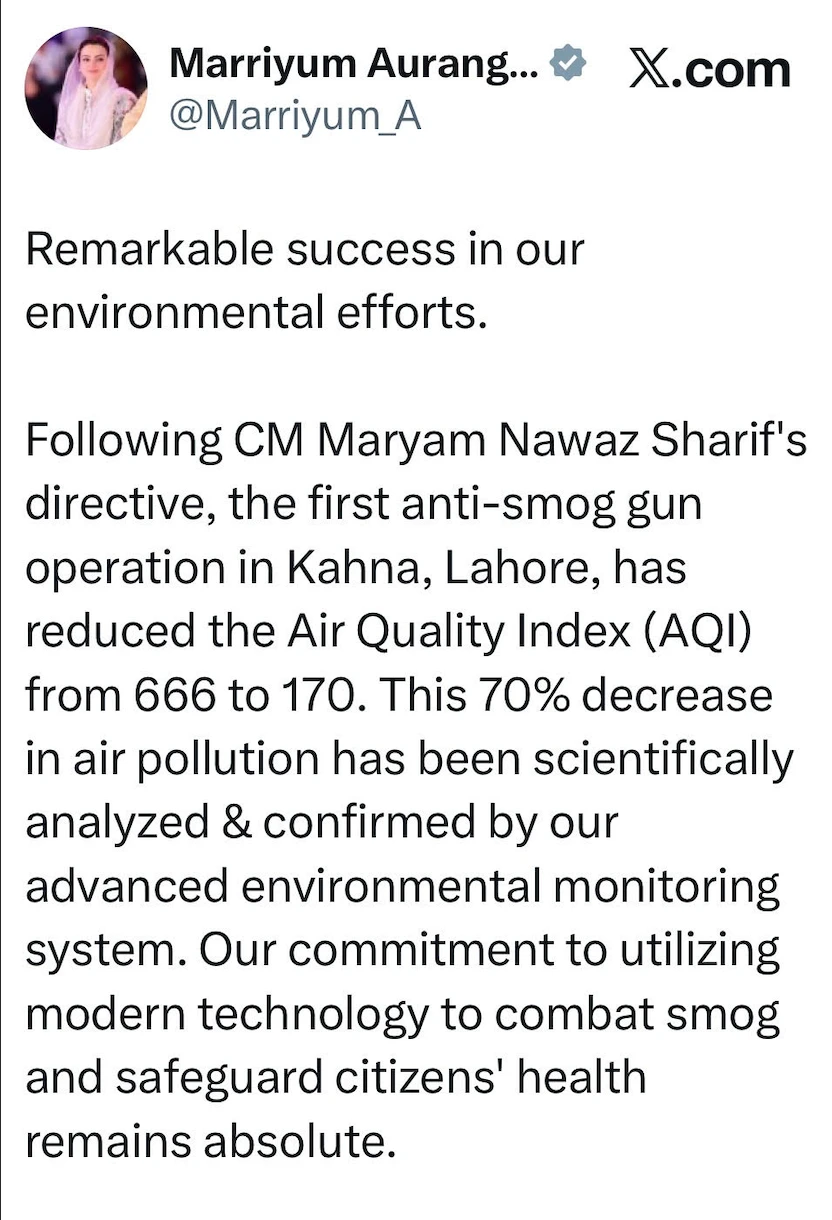

Outside this real Lahore, the online air feels just as toxic. Punjab’s Senior Minister Marriyum Aurangzeb’s claims of her government’s effort to curb smog are routinely cancelled.

Throughout October, Marriyum Aurangzeb posted frequently about efforts to combat toxic air. Her feed was filled with announcements of new technology and bold claims of progress — and replies were far less enthusiastic.

When she posted on X, “Today, thank God, Punjab has its own Air Quality Monitoring War Room in Lahore with an AI-based forecasting system, 41 air-quality monitors, including 14 mobile ones, and by June 2026, 100 monitors will be operational across the province”, environmental researcher Dr Imran Khalid responded, “Focus on consensus building with farmers (stubble burning) and eliminating poor fuels — whether in vehicles or brick kilns”.

In another X post, Aurangzeb said her government has “provided thousands of modern machines to farmers to curb crop burning. Over 11,000 brick kilns are now QR-coded and shifting to Zig-Zag technology, while 8,000 industries are under real-time emission monitoring”. Hassan Aftab, a fellow at Oxford University, replied, “BTW only less than 14% of the brick kilns are zigzag in Punjab. Zigzag doesn't mean there's no air pollution from brick kilns, particulate matter and CO emissions are only around 25% lower when shifting to zigzag from traditional kilns”.

And when she posted, “the first anti-smog gun operation in Kahna, Lahore, has reduced the Air Quality Index (AQI) from 666 to 170. This 70% decrease in air pollution has been scientifically analyzed & confirmed by our advanced environmental monitoring system,” Climate and public policy expert Dawar Butt replied: “This is 15 x 11,000 litres of water being wasted in a city where you don’t get groundwater till you drill 80 feet below surface. Can someone answer why this is AQI 666 in the first place?”

When TV host Hamid Mir remarked that “Lahore’s air quality hasn’t improved in four years”, linking an old article, Aurangzeb replied: “Hamid bhai, you’ll have to keep writing like this for some more years — in countries where smog has been eliminated, it’s taken 10–20 years”.

To another tweet on the smog gun by her, an X user, Amir Akbar, shot back: “Tauba! You guys are wasting too much money on this nonsense — making people pagal!”

***

The clock turns again. Another year. The curtain lifts, revealing a thicker haze — a deeper gloom. A minister steps out, squinting upward, shielding her eyes with practiced hands, gestures inherited from brighter days. She searches for the sun. There is only the dull hum of a sky that has lost its colour.

The air trembles with the cough of the city. Fields of withered crops bow. The minister murmurs, her men look at the horizon, searching for the sun. Only dust swirls in slow motion.

Meanwhile, on the roads of Lahore, air monitoring squads are conspicuous — green vehicles emblazoned with Maryam Nawaz’s picture, rolling through the haze like sentinels of clean air. But, one wonders: in trying to clear the air, are they only choking the city’s streets further?

Two years ago in 2023, the Urban Unit revealed that more than 80 percent of Lahore’s pollution stems from the transport sector. To mend ways, the Punjab Transport Department made the Vehicle Inspection and Certification System (VICS) compulsory for public and commercial vehicles, which entails operators to obtain a valid vehicle fitness certificate from designated centres to ensure their vehicles meet safety and emissions standards.

Likewise, the Punjab Environment Protection Agency (EPA) rolled out a Green Sticker initiative for private vehicles, where those that pass the emissions test receive a windshield sticker, to serve as proof of compliance with emission standards.

So, in the peak of summer this year, queues of cars snaked around various parts of Lahore — drivers sweating it out in the heat, eager to get their Green Stickers and do their bit for cleaner air. The deadline for free emissions testing was June 30, which was then bumped to August 31, 2025. The rush fizzled. Later, as if jolted awake, the EPA announced vehicles without valid Green Stickers will be seized from November 15 onwards, according to news reports. A crackdown seems to be underway.

Meanwhile, on the roads of Lahore, air monitoring squads are conspicuous — green vehicles emblazoned with Maryam Nawaz’s picture, rolling through the haze like sentinels of clean air. But, one wonders: in trying to clear the air, are they only choking the city’s streets further?

Alongside the Punjab government’s e-vehicle policy, Euro-5 vows are repeated and results are awaited.

Khawar Jillani, CEO of Asia Petroleum Limited, says that aging vehicles — “sometimes those from the 1970s” — rather than Euro-5 fuel, are the bigger culprit. Acknowledging new cars are unaffordable for many, he urges the government to expand and encourage public transport use through innovative schemes.

The World Bank has stepped in with a USD300 million International Development Association loan, for the Punjab Clean Air Program (PCAP), aimed to strengthen air quality management and combat air pollution, in sectors such as transport, agriculture, industry, energy and municipal services.

It aims to reduce PM2.5 levels by 35% over the next decade, significantly decreasing the incidence of respiratory illnesses and other pollution-related health issues for the 13 million residents of Lahore Division. Key interventions include the investment of 5000 super seeders to reduce crop residue burning, the introduction of 600 electric buses, the expansion of regulatory-grade air quality monitoring stations and the enhancement of fuel quality testing through the establishment of two new fuel testing laboratories.

Lahore now boasts a network of air-quality monitors. Around 12 reference-grade stations and many low-cost sensors have been installed to boost coverage across the city. The Urban Unit, a multi-disciplinary organisation that is centred upon data repository, now has an open-access, real-time particulate pollution monitoring network in Pakistan, through the installation of 160 PM2.5 monitors across 14 major cities. Of these 23 monitors are installed in Lahore itself, with the promise of many more.

***

The wind changes direction. The clock turns. Ten years? No — twenty? The stage bursts suddenly with light. Children dance. Old people smile. Crops sway. A cheer rises: “Long live the season of no-smog!”

For the smog to clear, the road ahead is steep. For now, the policy, its execution and the public’s response are like a bag of dirty laundry — waiting to be washed and aired in bright winter sunlight.