Plays that push boundaries, or bring untold stories to light, are rare in Pakistan because they’re risky. They don’t guarantee big audiences, sponsorships or glowing reviews. Theatre, despite the recent rise in popularity, is hardly a thriving career here; those who do make it to the stage often end up working on plays that follow a safe, familiar script—stories that sell tickets without making anyone uncomfortable rather than risk telling more provocative stories. But sometimes, a group of artists decides to take that risk anyway. When they do, magic happens.

Recently, one such moment unfolded in Karachi, where the theatre collective Mauj. staged a live adaptation of the Hindu epic Ramayana. In a country where theatre already struggles and political and religious tensions are always bubbling under the surface, this team of Pakistani artists chose to bring one of South Asia’s most celebrated mythological tales to a Muslim-majority audience. They didn’t just stage it—they reimagined it, using artificial intelligence to create visuals that turned a centuries-old story into a high-tech spectacle.

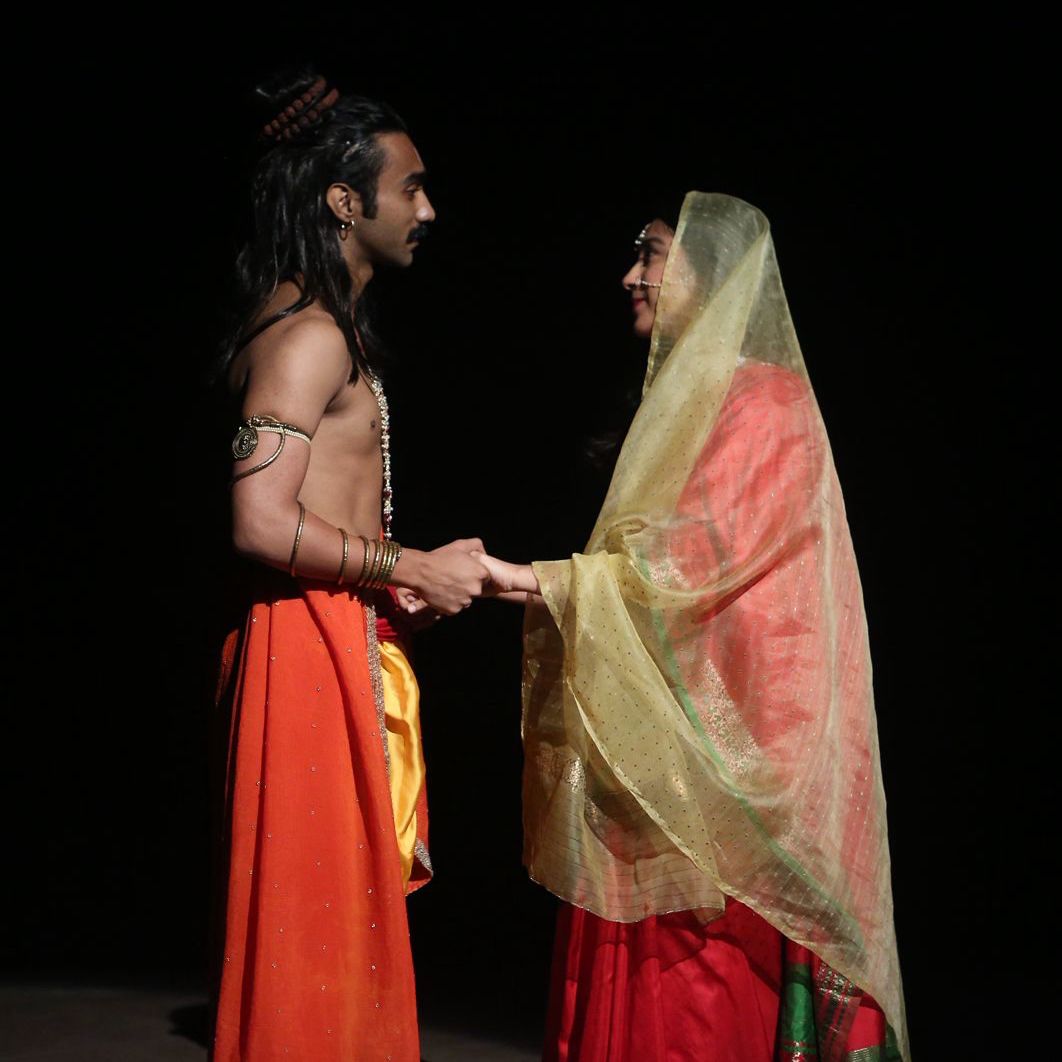

Performed at the Arts Council of Pakistan in Karachi between July 11th and 13th, Ramayana was directed by Yogeshwar Karera and produced by Raana Kazmi. The show was a blend of great storytelling with smart use of AI, earning praise for performances, lighting, music and colourful costumes, along with captivating stage design.

In Hindu culture, the Ramayana tells the story of Prince Ram, who is exiled to the forest with his wife Sita and brother Lakshman. When Sita is abducted by the demon king Ravan, Ram sets out to rescue her with the help of the god Hanuman. The tale celebrates themes of duty, devotion and the triumph of good over evil.

Since then, Ramayana has been doing the rounds on social media, with people from both Pakistan and India sharing the videos, leaving comments full of surprise, admiration and, above all, hope.

The audience, which included both Muslim and Hindu communities, felt these nuances. Many were simply amazed at not just the story, but by the fact that it was being told in Pakistan, with some admitting that they had never imagined seeing a Hindu epic portrayed live in their city.

Curious about the vision and intent behind this rare cultural crossover, I reached out to the cast and crew, particularly Yogeshwar, to find out what drew him to this story and how he brought it to life on stage.

Yogeshwar Karera spoke to me about what inspired him to choose Ramayana, saying, “I wanted to do something different, a gallery of sorts where Ram could travel from one scene to another, allowing viewers to follow that journey seamlessly. Honestly, I never thought it would be possible to tell such a comprehensive story within ninety minutes. The idea had been with me since I was five years old, ever since I first watched Ramayana on Star Plus. In Pakistan the story is rarely talked about, only surfacing here and there. I certainly didn’t expect the cultural ripple effect it had in India, where major media outlets picked it up. When we staged it earlier at a different venue, it felt like performing any other play, it didn’t spark anything close to what we’re seeing now.”

A lot of this credit also goes to the lead performers. Samhan Ghazi, who played Raavan, delivered a performance that was both commanding and layered. His presence on stage exuded menace, yet he allowed glimpses of vulnerability to seep through, making the antagonist more complex than caricature. As Ram, Ashmal Lalwany brought a calm dignity to the role, embodying the character’s moral strength and unwavering resolve with sincerity. His measured expressions and deliberate movements gave the performance a quiet weight. Raana Kazmi’s Sita was a portrait of grace under pressure. Her stillness and poise often spoke louder than words. She conveyed the quiet power of faith with an understated intensity that lingered long after the scene ended.

Playing deeply revered characters from Hindu mythology must have come with a unique sense of responsibility. I wanted to understand what the actors thought when they took on these roles and how they prepared for them and spoke to the leads about their process.

Ghazi shared that for him every text holds value, no matter the role being played on stage and that he tried to approach the character with sensitivity and honesty, dedicating time to reading and researching to do justice to the performance. Ghazi further said that there was no backlash or pressure while taking on the role, nor did he feel any insecurity.

Ashmal Lalwany who played Ram, on the other hand, admitted feeling extremely nervous before taking on the role. He explained that portraying such an iconic figure was not just about playing a character, it was about representing a belief system followed by millions of people. Physical expectations added to the pressure, as his own appearance was far from how Ram is traditionally imagined. He feared audiences might not accept this difference, but Karera helped him focus on embodying Ram’s ideology, personality and mannerisms instead.

The Ramayana is a story that prominently features a war fought by men, but Sita’s internal struggle provides a crucial feminine foil to the more obvious action taking place.

“Sita isn’t just a character, she carries immense meaning and responsibility,” says Raana Kazmi, on playing the main female lead. “While the men were off fighting their wars, women like her were involved in their own silent, but equally intense battles. It required a lot of emotional preparation to capture that strength and restraint.”

A moment that stayed with Kazmi was when Hanuman offers to carry Sita back to Ram. She refuses, because touching another man goes against her beliefs, choosing instead to wait for Ram to fight Raavan, to defeat evil himself and prove his virtue.

“That unflinching faith, that quiet strength in the face of pain and captivity, was powerful to portray,” says Kazmi.

The audience, which included both Muslim and Hindu communities, felt these nuances. Many were simply amazed at not just the story, but by the fact that it was being told in Pakistan, with some admitting that they had never imagined seeing a Hindu epic portrayed live in their city.

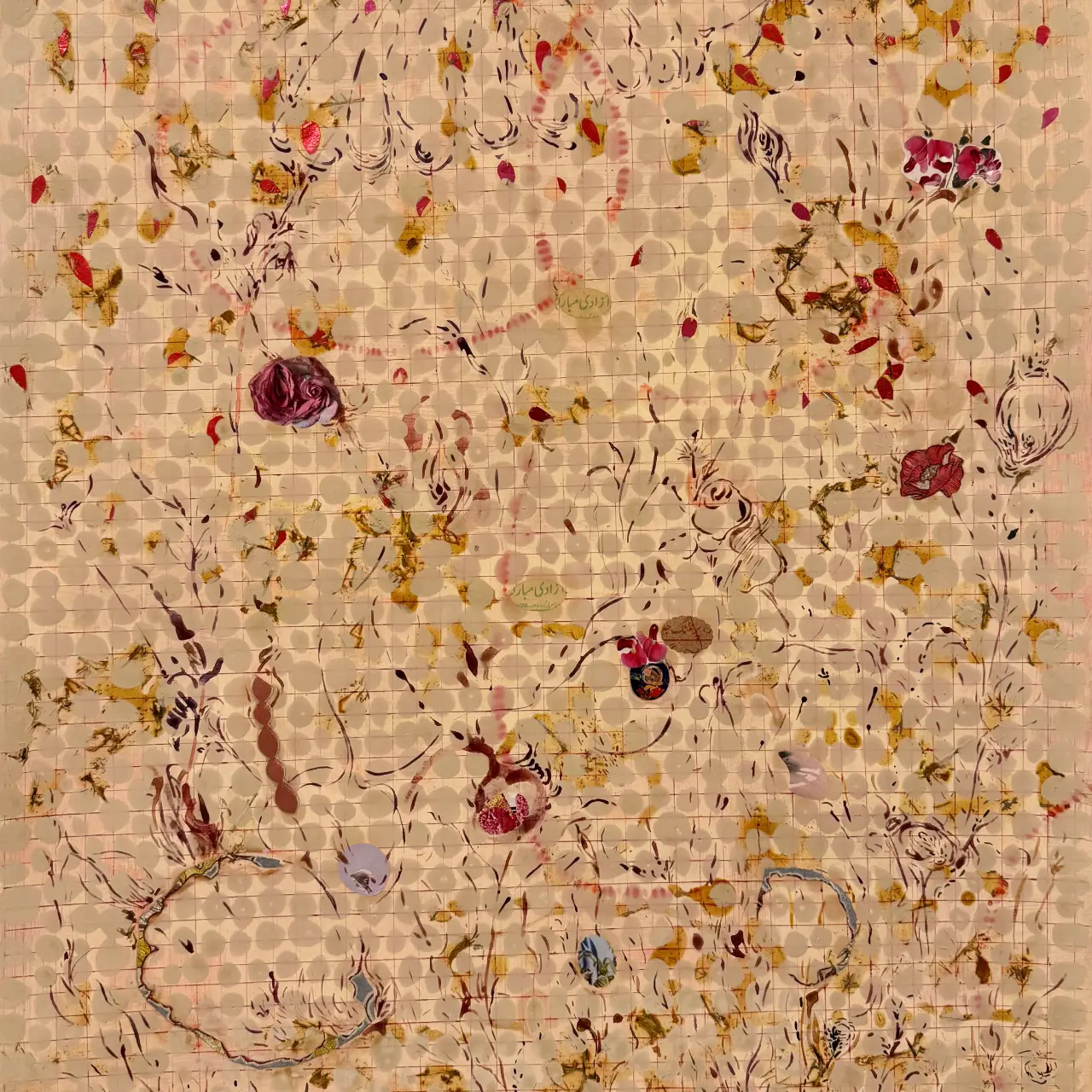

Others praised the cinematic design, the live music and the way AI was used not as a gimmick, but as a bridge between ancient tradition and modern storytelling. Speaking of integrating AI to enhance a centuries-old epic, Karera said that while he is aware of the criticism against AI, it became a practical, cost-cutting solution that allowed him to add depth to the theatre experience.

For a region where headlines are often dominated by political hostility, this play did something extraordinary. It reminded people that art doesn’t care about borders. Stories, music, and emotions don’t need visas to cross from one side to the other.

Talking about how theatre and storytelling succeed in creating harmony where political narratives often fall short, Karera said that he doesn’t think theatre should be expected to do that. “Politics should be left to politics. It isn’t theatre’s responsibility to create harmony. At best, it can serve as a side quest, not the main mission. For theatre, the primary goal is to tell incredible stories that resonate deeply with people,” says Karera. “If those stories happen to bring people together, foster empathy, or create harmony in society, then that’s a welcome supplementary outcome. But it should be seen as a natural by-product, not the driving purpose.”

It’s not that this production erased the realities of conflict—India and Pakistan remain tangled in disputes over water, terrorism, and territory. But for a couple of hours inside that theatre, people shared something pure and non-political; a story about love, courage, loss and faith.

This is what makes the Mauj. production powerful. It was a quiet act of rebellion against the idea that we are too different to understand each other. Ramayana reminded us that before politics drew lines in the sand, people in this region shared tales and traditions and that sometimes all it takes is a handful of brave artists to bring that truth back to life.

All visuals courtesy of the author.