The sun hovers low. Outside the car is a sultry 40°C, despite it being only May, almost sunset. We drive by the Kheri Murat hills. My father once said he wanted to build a tidy little hut in the womb of those hills, away from the chaos of the city. Did we know, when he said that, when we were children and driving down this motorway that has, over years, acquired coat after fresh coat of meaning, did we know even then that none of us would ever get away from the cities, that the house in the womb of the hill wasn’t for us?

My mother and I are driving south on the M2, straight from the Islamabad airport. We retrace the nape of hilly necks, the undulating plateau bordered by eucalyptus trees, the intermittent flatness where you can see far into the horizon. And on the horizon is the sun, now behind the hills, now glaring at us, orange, fiery, even as it sinks. Now, it has fully sunk. We exit the motorway and make our way past more hillocks, rusty bridges, a small mosque where my father sometimes prays on the way to the village. Now, we’re driving in the dark, balancing caution with haste. We must get there soon. My mother’s phone keeps lighting up.

“Where are you?”

“How far?”

Now, we reach the bypass that will take us to the house in the village. Now, we are turning onto the street. Now, my mother flings the door open. Having flown, then driven, to arrive at the beloved’s feet, now, finally, she walks. Now, we rush through a swarm of men, some of whom recognise us and wordlessly step out of the way. Now, my mother is inside the gate. Now, she begins to wail. Now, she bends down over her mother, peaceful, shrouded, awaiting her eldest child before she is buried.

We flew back from New Jersey upon news that my mother’s mother—my grandmother is the more colloquial way of putting it, but how can it supersede the fact that it was her mother—was very sick. The flights were booked at the last minute, so my mother and I weren’t seated next to one another. Two hours into the flight from JFK to Doha, she said she would try to get some rest. We planned to rush to the hospital from the airport. Returning to her seat, she turned on the in-flight WiFi. A few minutes later, I saw her walking back to me, an Etihad Airways polythene tote bag gripped neatly in her hands. She sat down in the empty seat next to me.

“Bibi Amma has passed,” she said, in English.

Three months on, that image continues to bewilder me. She is walking over, everything about her orderly and compressed, her hands firm around the tote carrying the possessions one keeps with oneself on the plane—phone, passport, eye mask—to tell me, her daughter, in terse, precise English, the language of the newspaper and the workplace, that her mother is no more.

The rest of the plane ride is a blur. She calls my father, who is still in the US. She calls her sisters. She plans with her brother about the burial. By the time we land in Doha, my grandmother, Bibi Sakina, has been lovingly washed and shrouded, awaiting only my mother before she is laid to rest.

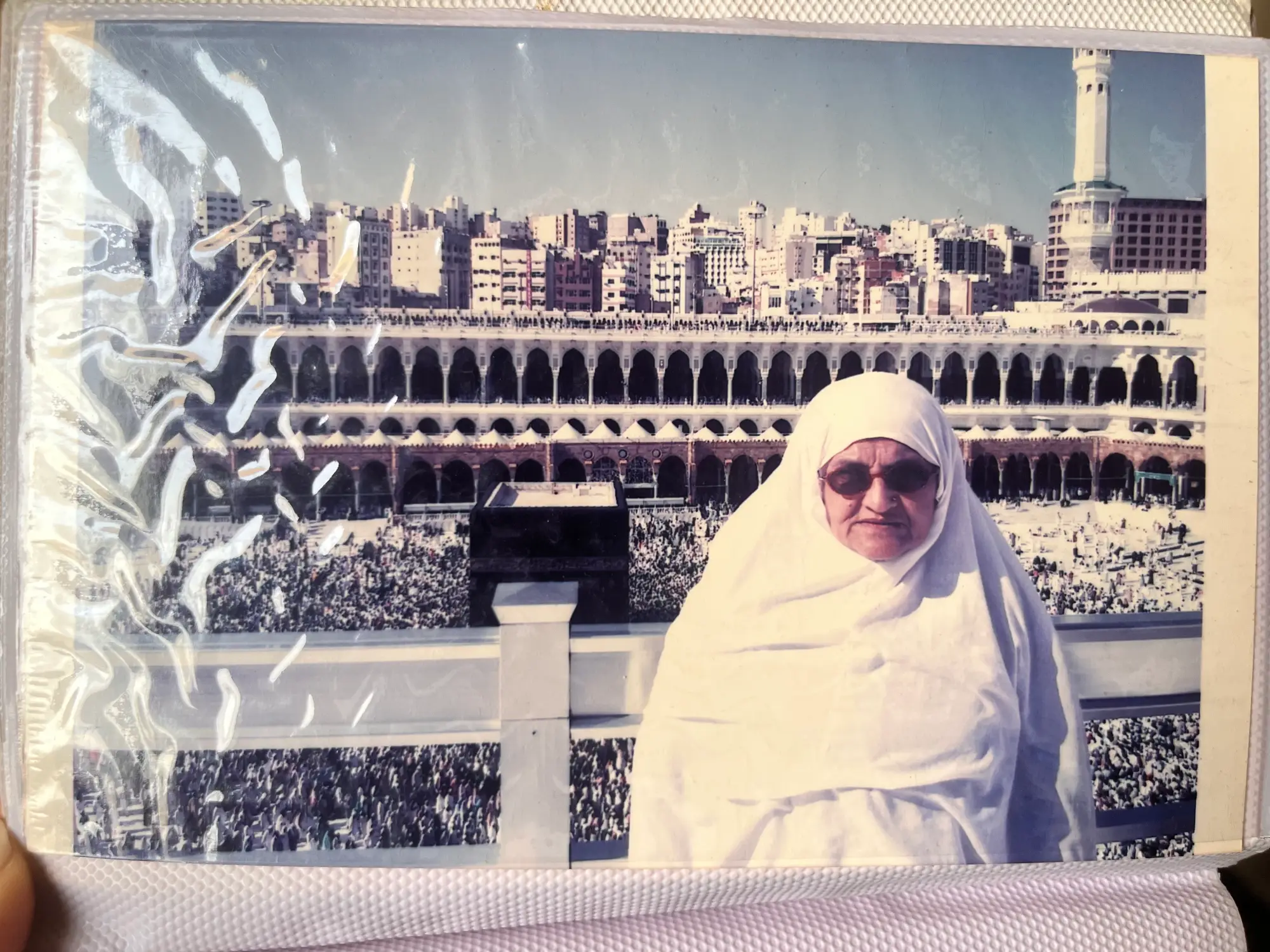

My grandmother was born in 1944. Records from that time can rarely be trusted, but she had recollections of the Partition, which means that she was at least 3 or 4 at the time. She was 81 when she passed. She left behind 7 children, 18 grandchildren, and 3 great-grandchildren. She survived all her siblings. She was up and walking less than a week before her death. She had undergone every rite of passage of a traditionally successful life—wedding, parenthood, pilgrimage to Makkah, the weddings of her children, raising her grandchildren, even attending a few of their weddings. In 2017, she flew to the US to attend the American ceremony for my wedding. There’s a photo of her sitting on the red steps of Times Square. There’s a photo of her in a beautiful off-white shalwar kameez at my wedding. There’s a photo of her looking unbearably cool in shades and a deep purple outfit, against the sun-dappled lawns of my brother’s liberal arts college. There are so many ways to die. It’s hard to be certain, from this side of the divide, but by all signs, she had a good death. An hour or two before she passed, she prayed to God in Urdu, a fact that also puzzles me—Urdu was her formal language. She loudly said the shahada. To the faithful, that is a wonderful omen for one’s afterlife. To me, it means that my grandmother was sentient till the end, and had come to terms with, even welcomed, her departure. Not everyone gets to do that. My brother told me of an Arabic phrase that sums it up—“husn al khitam”. A beautiful ending.

The problem, as always, is of the living. In the days after the death, I find my mother confounded by grief, lost, bewildered. She acts like a stranger, keeps breaking down. I have never seen my mother weep in my life. I look at my aunts and uncles, those witty, sparring, lively people who have towered over me my entire life, and see them battered by grief. My cousins, desolate, all with their own stories, all convinced by my grandmother’s expansive heart that they were the favourite grandchild—after all, how much love can one person contain within themselves? Endless, we realise, as we speak to distant relatives, second and third cousins, acquaintances, and find out that our grandmother had in fact called them a week ago, to ask about a sick child or ailing parent. In the cities, we are now of the notion that real obligations begin and end with the nuclear family—children, spouses, parents, siblings. My grandmother was one of the last surviving members of the older generation, whose definition of community was a vast net. Again and again, we keep pointing out to ourselves and others that we haven’t lost just a person, but a way of life, an outlook of grace and abundance. Dhoondo ge agar mulkon mulkon, milne ke nahi nayab hein hum.

The problem, as always, is of the living.

The days of mourning help. In the village, there is a theatre. When the men come in to pick up the charpai, the women scream in unison. “No, please, no, not yet,” they plead, knowing well that the sun has long set, it is past time. The men continue, stoic despite their gleaming wet faces, to lift the charpai. The morning after the burial, we go to the graveyard to put flowers and light incense. When we return, every woman who has come to mourn asks, “Did Bibi speak to you? Did she say anything?” What an absurd thing to say, I think. Soon I realise it is a script, well-practiced, rehearsed repeatedly in this place where communities still gather continually for funerals, where the neighbourhood mosque still announces deaths and funeral times over the loudspeaker. It is all performance, well-honed, intended to keep the abyss at bay. We wipe our eyes with dupattas, we sit in the stifling heat and move the beads of the rosary, we remember and repeat, we repeat, we repeat. We hear the same story told back to us, and we don’t tell the person, “Yes, I know, I said this.” We serve greasy curries to visitors, we rush around with cups of chai. If I sound like I am playing anthropologist, I cannot help it; the sun is setting on this world, and I am recording it, so I can read in the dark.

After my mother tells me, in the plane hurtling in the skies over the Atlantic, that her mother has passed, I pick up my phone. I look up a verse that has been echoing in my head ever since the plane took off.

alam nasibon jigar figaron

ki subah aflak par nahi hai

jahan pe hum tum khare hein donon

sahar ka raushan ufuq yahin hai

For the rest of the plane ride, I repeat the poem to myself like an incantation. Earlier in the same poem, Faiz writes,

Yeh raat uss dard ka shajar hai

Jo mujh se tujh se azeem tar hai

This grief, he writes, is nobler than you and me. Many years ago, during winter break from college, I wanted to drive down to Lahore to visit Faiz’s grave. There was political unrest in the country, and my father said the trip was out of the question. In a moment of frustration, he snapped, “He’s a poet, Dur e Aziz! Can you stop acting like he’s God?”

Indeed, he’s not God. Many times, though, he has helped me endure what God puts us through.

Throughout the first night in the village, as I toss around on the floor—the house is teeming with people and everyone is lying wherever they can find space—I can’t think, or even weep. All I tell myself is, yeh mujh se tujh se azeem tar hai.

My grandmother was born in the same village where we buried her. As the only sister, and youngest sibling, to seven brothers, she was, as my mother puts it in Punjabi, “daadi.” Roughly, this translates to bossy. She studied till tenth grade, uncommon for that milieu. She was then married into a family settled in Multan, where my grandfather was a grains trader.

Once, I tried to interview her for an oral history project. My hope was to interview the older members of the family, to record their earliest impressions, their remembrances about society, the changing life of the village. She played along for about five minutes, clearly bored. Then she told me, “Beta, I’m uneducated. Why don’t you ask other more learned people about history?”

She knew enough of history. She loved watching the news. When my brother called her, they had long chats on the most recent political scandal. But that was not the history that interested her. Feminine history, intertwined though it is with the masculine, is its own subject. It’s the tidy ledger my grandmother kept, noting down every gift given at her children’s weddings, so she could repay it accordingly when time came. It’s the recipes for panjeeri, for aloo gosht, for tripe, for homemade porridge. It’s the journeys taken from Multan to Rawalpindi each time one of her daughters had a baby. It’s the concoctions for colic, the hacks for indigestion, the reuse of old cloth for diapers. It’s the diligence with which she visited the sick, the mourning, the newly married, and the young mothers every time she went to the village. It’s the constant vigil of the mother, the grandmother, the aunt, the Bibi.

When my parents introduced my then-fiancé, a Portuguese-American from New Jersey, to my family, there were murmurings of discontent and alarm. Not from my grandmother, though, who embraced him like a long-lost son, who put a ring on his finger the first time she met him. A product of the village, she was somehow able to keep the open-hearted generosity of that place while eschewing its narrow ambitions. Herself a mother of seven children, she advised my mother to stop at two. She danced an enthusiastic luddi at my American wedding. I will never forget, though, when I took her to a church in Ohio. My husband excitedly showed her the pews, the emaciated Jesus on the cross, the gilded roof of the Catholic church. She looked up in silent contemplation and we were sure that she was in awe; the church was far grander than most mosques. After a while, she turned to me and said, “Beta, mein har roz dua karti huun ke is ka sara khandan kalma parh le. Inshallah.” As we left, my husband kept eagerly asking me what she had said; I didn’t have the heart to tell him.

My dear Bibi Amma, with her steadfast faith, who greeted us all with a delicious twinkle in the eye, who gave the longest, tightest hugs I have had the luck to receive, whose string of prayers was endless, continuing on the phone for minutes while my brothers and I repeatedly muttered “Ameen, Ameen,” my dear Bibi Amma who had started leaning a little with age, yet who was still strong enough to push my daughter—Sakina, named after her—on the swing the last time I saw her. My older Sakina, who must have once been a baby like my little Sakina, whom someone had once fed and cherished and held, is no more.

The common wisdom is that one turns brittle with age. I have not found that to be the case. The past few years have brought a series of deep losses, and each wound has stung more than the previous one. Nasha barhta hai sharabein jo sharabon mein milen, wrote Ahmed Faraz, and so it is with grief—each new loss brings with it echoes of prior ones. Grief is accretive. My father, a steady Sunni, once told me that he appreciates the commemoration of Muharram, because the grief of Hussain keeps the heart soft. That might be the case for all grief. The heart, like the little pots and pans of clay we made as children, keeps turning again and again into mud.

All personal photographs are courtesy of the author.

Lead image courtesy of the artist, Sahyr Sayed.