On a Monday morning in 1987, three men were brought to the National Coaching Centre in Karachi to be flogged. As they were led into the grounds by the police, there was a round of applause by schoolchildren, who were coincidentally there to practice for sports games. As the men were flogged—one of whom screamed to be spared—children whooped and clapped along; when the flogging ended, they began a chant: once more, once more.

I have thought about this story a lot over the years. I wonder who these children were, who they grew up to become; if our paths ever crossed in the years I lived in Karachi, if they ever drove past the centre and told their kids about what they’d seen, cheered on.

This story might seem outlandish and the kind of account you can easily dismiss as from a different dictatorial era. Perhaps you might believe that society has evolved beyond the point of cheering on public flagellations.

Or has it?

Bloodlust doesn’t always come packaged in these handy little scenes and vignettes to explain how it has become part of the daily discourse: kaat do, jala do, phenk do. Barely sanitised in English: “I don't believe in the death penalty but…” … “they should all be hanged from the trees…” … “no man would ever dare do this again…” “justice has been served”. Death threats have become so common that they are almost everywhere: in comments sections, in conversations, on the streets.

There is an acceptability to the idea of public suffering, of putting someone to death, whether it is at the hands of the state, a mob or the comments section. This is not some throwback to the past; this has become enshrined in the way people speak, the exceptions society has carved out to make death acceptable and whatever contradictions in their beliefs let people sleep at night.

There’s no bigger test of this than when high-profile crimes happen: militant attacks, assassinations, rape, child abuse, murder. Somehow, then, the state, its people—liberals, conservatives, right-wingers, et al—unite in the belief that now, death is acceptable. People start baying just as much for death as the mobs lynching men they believe to be muggers. (There’s no moral equivalence, one might say, but you’re still asking for someone who is guaranteed a right to a fair trial to be put to death without one.)

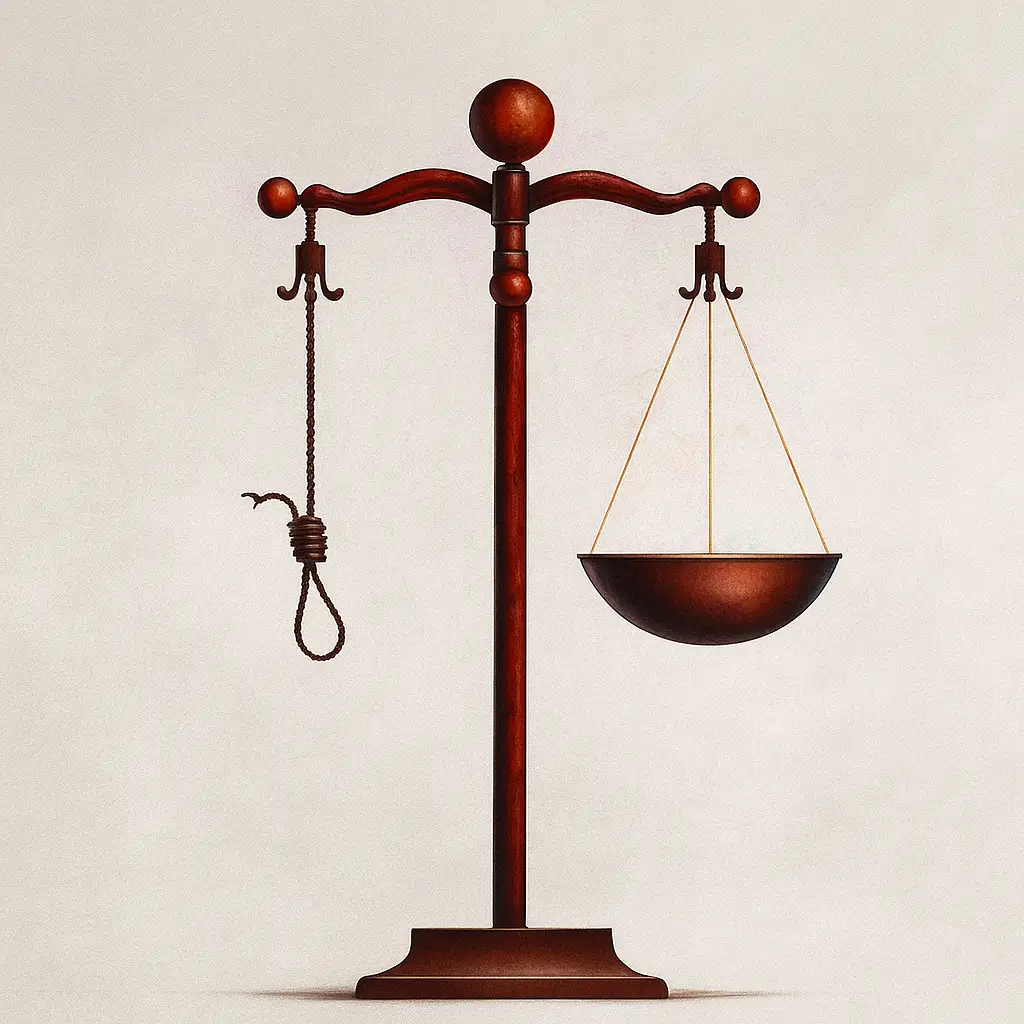

What has the death penalty achieved other than generating an endlessly nauseating cycle of bloodlust that can somehow only be appeased by hanging people?

Over the years, it has been truly astounding to even see people go after lawyers for representing someone accused of murder—almost as if the shock at a crime means the decimation of civil liberties, of fundamental rights; almost as if everyone has forgotten what the job of a lawyer is in the first place. It has become remarkably easy—remarkably acceptable, even—for someone to say, with a straight face and no clue that they are about to say the most blatantly hypocritical thing they’ve ever uttered: I don’t believe in the death penalty / I believe in human rights BUT …

What they mean is that in this case, in a case that they are personally affected by, the state should execute someone, but not in any of the other cases in which they believe the state has no right to execute someone. I suppose this kind of moral juggling must work for people. After all, everything from extrajudicial killings to internment camps to military trials was acceptable, even lauded as a state policy until it started to impact people of a certain class, because, ultimately, there are no exceptions when it comes to the abrogation of civil rights.

But why is it so easy for people to make these exceptions? For one, the death penalty is enshrined in law. There’s a sense that the convicted must suffer—which is why there have been calls for chemical castrations and for public executions, an amplification of punishment worse than execution. There is a belief that the justice system has failed; that it can never deliver, and so in lieu of that, death is somehow not only acceptable, but the only way in which justice can be served. What is remarkable—though of course, memories are short and convenient, so it isn’t remarkable at all—is that every time there’s a high profile case, a death sentence is invoked as this final, one-time magic bullet: just once, just this time, hang the convict and everything will be fine. This time, justice will be served. People will automatically be reformed; would-be rapists and murderers will take one look at the man hanging by a noose and somehow stop committing crimes. It’ll be a wake-up call. The law will have reigned.

As it turns out, none of these are deterrents. In 2014, when the unofficial moratorium on the death penalty was lifted, Pakistani television channels broadcast footage of the convicts still hanging from the noose. Photos of executions have appeared in newspapers, including in the 1970s. The numbers of people sentenced to death is increasing; in 2024, according to the Justice Project Pakistan’s annual prison data report, 3,646 prisoners were on death row, up from 3,604 the year before.

Even with over 3,000 people sentenced to death, one must ask: has crime stopped? The death penalty as a deterrent to crime argument has been debunked so comprehensively—just in Pakistan alone—that it is almost wondrous to see people still holding on to this belief. Tacking death onto terrorism charges has not abated terrorism; muggings continue regardless of how many suspected robbers are lynched in public; footage of honour killings is on your cell phones and women continue to be killed in their homes. What has the death penalty achieved other than generating an endlessly nauseating cycle of bloodlust that can somehow only be appeased by hanging people?

It is ludicrous that there is a world in which ‘mugger with toy gun lynched’ is something that takes place without comment, or outrage; in which death becomes a game, and yet one that we seem to keep playing, year after year, each time thinking that this time, just this once, once more, society will somehow change.

I understand the counter-arguments too: the rich buy their way out of prison. (Sure, then change those laws—an argument no one ever seems to want to see through.) Have you taken a look at our prisons? (Have you?) Nothing happens to people in prison. (What would you prefer to happen? What do people want for those accused and convicted of crimes to happen to them at the hands of law enforcement and jail authorities? How much torture will be enough?)

The visceral, true frustration and anger that this keeps happening is completely understandable too; that crimes perpetrated against innocent people have become more violent, abhorrent, frequent, that the rich walk free, that the justice system does not work.

But what is the solution? A society that chants “once more”? A society where lynchings have become so common that it almost feels like it was a million years ago that the footage of lynchings had the capacity to shock—it was just in 2011 that footage of two boys killed by a mob in Sialkot shocked people; that the account of a man killed by Rangers personnel in a park led to a trial. Now, however, death has become a frequently meted out punishment in your mohalla.

Here’s a sampling of headlines from Dawn: “Angry mob lynches suspected mugger.” (March 16, 2025); “Angry mob lynches suspected mugger in Orangi Town” (April 3, 2025); “Mob lynches suspected mugger in Ittehad Town” (June 6, 2024); “Police save suspected robbers from Lynch mob in New Karachi” (April 28, 2024); “Mugger with toy gun lynched” (July 14, 2023); “One suspected mugger lynched, two others injured by mob in Karachi” (November 4, 2022). I’d continue but the nausea has yet to abate. It is ludicrous that there is a world in which ‘mugger with toy gun lynched’ is something that takes place without comment, or outrage; in which death becomes a game, and yet one that we seem to keep playing, year after year, each time thinking that this time, just this once, once more, society will somehow change. Once more.