Every year in the month of May, Europe’s largest, most significant cultural event—the Venice Biennale (La Biennale di Venezia)—opens to the public in Italy, with each year alternating between art and architecture. The city transforms, rents skyrocket and Venice teems with thousands of visitors from across the world. As preparations for the 2025 architecture biennale—the 19th International Architecture Exhibition titled ‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’— neared completion, a dizzying array of installations appeared across the city’s galleries, gardens and streets. Amongst contributions by over 750 participants were architectural propositions that played with lava and mycelium, seagrass and elephant dung, banana fibre and bamboo, along with AI, machines and robots. Not far from the Arsenale and Giardini on the evening of May 6, a team of Pakistani architects and researchers were diligently setting up the Pakistan Pavilion inside Spazio 996/A, a small shop-turned-gallery space. This year’s national participation—the third from Pakistan—was by an eight-member team spread across Lahore, Karachi and the U.S.: Arsalan Rafique, Ayesha Sarfraz, Sami Chohan and Madeeha Merchant, and architecture studios MAS/Architects (represented by Anique Azhar) and Coalesce Design Studio (represented by Salman Jawed, Mustafa Mehdi and Bilal Kapadia).

Inside the gallery that day, the air was slightly tense; parts of the exhibition material had been held back at customs, leaving very little time to fully assemble the exhibit for the pre-opening. This, however, was just a minor setback compared to the ‘four-day war’ between India and Pakistan, which unfolded between May 7–10. Largely due to last-minute visa acceptances, the team had landed in Venice only a day before, making it just in time before Pakistani airspace shut down completely for a week. With two members in the extended team unable to depart from Lahore, overall uncertainty regarding when (or if) those in Venice would be able to return home, and concern for their loved ones’ safety, work ground to a halt.

“It was around 10 pm in Venice when everyone’s phones started ringing, messages started pouring in, and we heard about multiple missile attacks. After that we were just paralysed. Nobody could work. We were also completely exhausted,” said Ayesha Sarfraz, alongside Arsalan Rafique and Anique Azhar in a collective meeting at the MAS/Architects studio in Lahore. “At one point we were actually wondering why we were even working on this pavilion if our country was heading towards a full-fledged war,” explained Anique Azhar.

Similar to several other Global South countries that have no permanent pavilions at the biennale and next to no support from their own governments, making this participation possible had already been a herculean task for the Pakistani team. Around them, bigger pavilions were ready to open, and with the biennale jury due to visit soon, the team had no choice but to push forward, occasionally pausing to sift through reams of fake news for updates from home.

(Fr)Agile Systems grapples with similar questions, actively choosing to go against Ratti’s solution-oriented motto by drawing attention to systemic problems. It advocates for AI—‘ancient intelligens’ instead of artificial intelligence—and in that, it joins the small but brilliant league of projects at the Venice Biennale that return to indigenous or ‘ancient’ knowledges, quietly listening to the land, before rushing to solve problems through design.

“Somehow or the other, we managed to finish most of the work that night, walking back home at 3 or 4 am,” the team recalled. On May 9, as conflict between the two countries entered its third consecutive day, the Pakistan Pavilion opened its doors to the public in Venice. Visitors gathered to hear the team speak about their work entitled (Fr)Agile Systems—a timely reminder of the country’s fragile-yet-agile disposition, unequal relationships between the Global North and Global South and the disproportionate burden of climate change on Pakistan.

Curator Carlo Ratti’s curatorial premise for the 2025 architecture biennale centres an approach that combines natural, artificial and collective intelligence to adapt to climate change. With a brief reference to floods in Sherpur (Bangladesh), his curatorial statement deems Venice “one of the most imperiled [cities] on Earth in the face of a changing climate”, mentions the Los Angeles wildfires, floods in Valencia and droughts in Sicily, finally calling for optimism and innovation for a rapidly altering world. He also invites participating countries to respond to a particular theme in their national pavilions: “One Place, One Solution” to “explore architectural strategies grounded in their local context, yet ones that are relevant to global challenges.” What solution could we possibly propose to adapt to centuries of barefaced exploitation, extraction and pollution by colonial powers? What kind of newer, smarter architectures must we continue to dream of as the Global North continues to fund ecocides, urbicides and genocides, whilst simultaneously speaking of climate change and adaptability? (The irony that Ratti is also one of the architects behind AquaPraca—an immaculately white, 4000 square feet raft-like structure jointly designed by CRA-Carlo Ratti Associati and Höweler + Yoon, soon to host 150 people for global climate dialogue, while floating towards COP30 in Brazil through the very same seas where countless migrants driven by climate inequity, conflict and economic disparity sink to its darkest depths—is heavy, almost laughable).

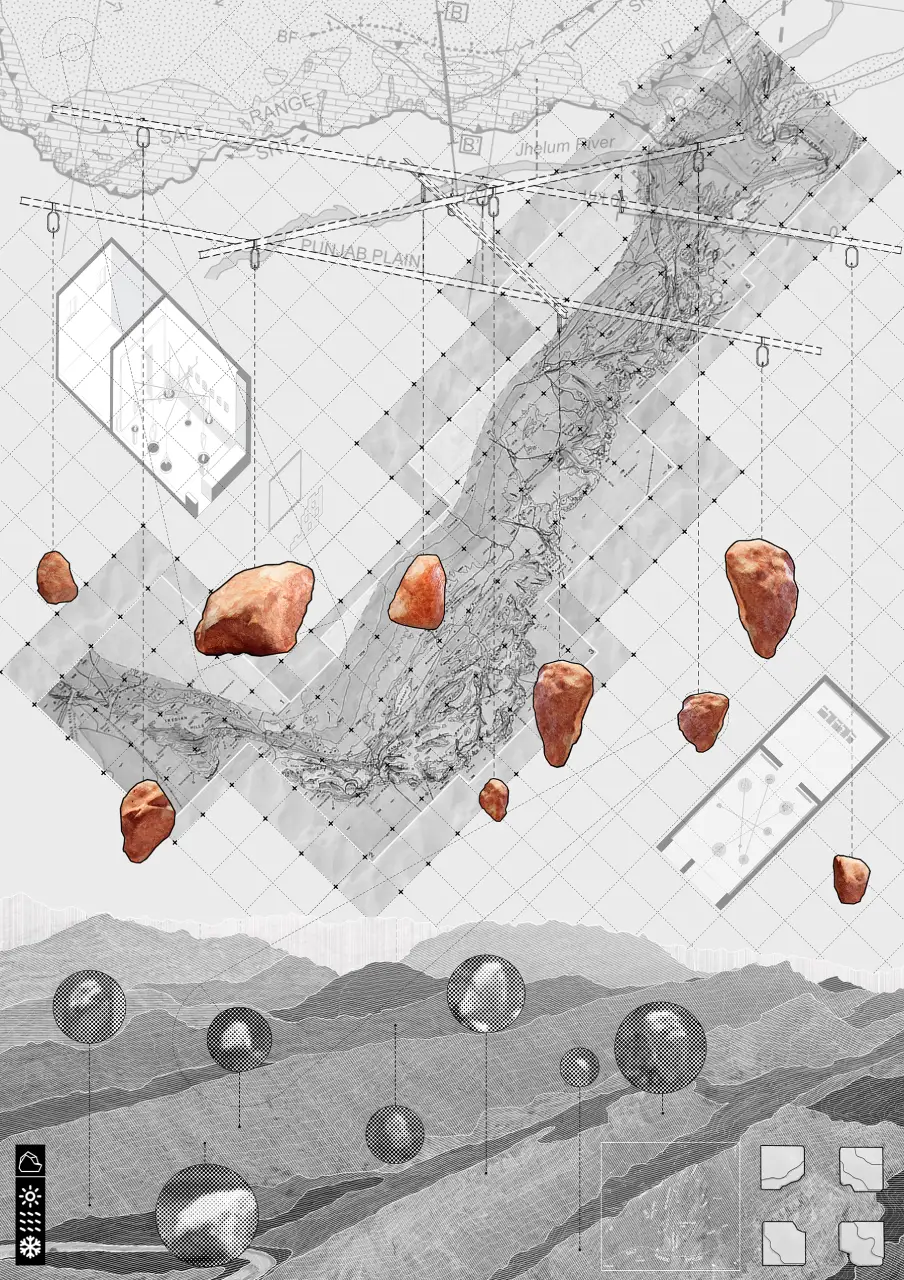

(Fr)Agile Systems grapples with similar questions, actively choosing to go against Ratti’s solution-oriented motto by drawing attention to systemic problems. It advocates for AI—‘ancient intelligens’ instead of artificial intelligence—and in that, it joins the small but brilliant league of projects at the Venice Biennale that return to indigenous or ‘ancient’ knowledges, quietly listening to the land, before rushing to solve problems through design. Through the gallery’s small glass front, the main installation is partially visible: thick, irregular chunks of pink-hued rock salt hang in delicate balance with steel wires, gently bobbing at various heights. The suspended structure recalls Alexander Calder’s playful mobiles and Bruno Munari’s Useless Machines, continuously transforming, shifting and recalibrating according to air pressure, touch and movement around it.

As the curatorial note mentions, the use of pink rock salt is not meant as a proposition to simply extract and consume a unique, distinctly Pakistani material from the second largest salt mine in the world. Instead, by manipulating its material properties alongside the Salt Range’s rich history, the work seeks to critique architects’ obsession with universal solutions and their disconnection with the land’s rhythms. The kinetic sculpture serves multiple roles: in its movement and state of perpetual imbalance and asymmetry, it is a metaphor for the inequities of the climate crisis forcing one to rethink terms such as ‘resilience’ and ‘adaptation’. Similarly, the melting and hardening of an indigenous material in an unfamiliar environment seeks to prompt conversations on site-specificity and granular, localised interventions, as opposed to top-down, globally applicable solutions.

What pushes the work beyond metaphor is a set of digital drawings, which focus solely on the Salt Range and the Khewra Salt Mines, highlighting the specificities of its terrain and its rich cultural heritage.

“When we look at the history of this area, there are lots of ruins, natural elements, temples, myths and legends; Al-Biruni measuring the Earth’s circumference at Nandana Fort, for instance. Or Alexander passing through this area. We began by excavating those narratives and then looked at how they could feed into subtle design interventions connecting visitors with multiple dimensions of the site—natural, spiritual, and so on,” explained Arsalan Rafique.

In a meticulously detailed, large-format cross-section of Khewra, the mine’s irregular subterranean tunnels contrast with newer, small-scale interventions that are almost surgical in their precision. Referring to acts of “building through subtraction”, the team elucidated: “The intention was never to improve the efficiency of the mine in any way, or add to colonial infrastructure, but to carve out supplementary spaces which capture specific moments and experiences.”

Meanwhile, the vast surface above is dotted with ‘follies’ engaging purely with elements of nature along with the Potohar Plateau’s wider histories. Zigzagging paths that stretch for miles, stepped platforms for rest and meditation, places to catch the sun and rain and decks for gazing at the stars, all imagined to be built with salt collected over several decades. These monumental geometric forms remind one of Louis Kahn’s Sher-e-Bangla Nagar in Dhaka, Bangladesh and gigantic astronomical instruments at the 18th century Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, India.

What is interesting is that these solid, towering architectures are also ephemeral by design, meant to be continually mended or to crumble into nothingness. In doing so, they challenge concepts of permanence and durability central to much of contemporary architectural practice and allude to practices of repair in indigenous cultures. Leaving much to the viewer’s imagination, the drawings also allow ample room for questions and stories. The scale, for instance, makes one immediately wonder how such huge structures would be built, and where this salt would come from. Is it being specifically extracted for building, and subsequently contradicting the very premise of the project? Or is it imagined to be pilfered from the salt supply reserved for nearby industrial factories—a deliberate act of slow, strategic smuggling from the very corporations that exploit our lands?

From an inert space for extraction, trade and tourism, Khewra becomes a medium for meditation on what the team calls “the diverse intelligences embedded in land, histories and relationships.” But, even as the project suggests that we tread sensitively and listen to the land’s many voices, it only touches lightly upon Khewra’s colonial history and present practices of unchecked extraction of other resources—limestone supplied to cement factories, for instance—that contribute heavily to ecological damage in and beyond the Salt Range. If explored in depth, it could have presented a much bolder critique of capitalist activity in the wider region, connecting it with existing conversations around Pakistan’s flawed, profit-driven development models which only serve to accelerate climate-induced disasters. The floods currently ravaging several parts of Pakistan only underscore this further, making it ever more urgent to mobilise against such harmful practices.

Despite these subtle contradictions, the Pakistan Pavilion is a sharp, modest insertion in an otherwise noisy, tech-heavy biennale; it effectively tackles what it sets out to do: drawing attention to the Global North’s role in what we now call the ‘climate crisis’ and insisting that a concerted effort towards global change will come from acknowledging the root of the problem. Other than the pavilion itself, Pakistan’s participation is worth appreciating for multiple other reasons. Considering the country’s recent entry into the world of fairs and biennales, and just a handful of cultural events to celebrate each year at home, encouraging and supporting fresh voices is crucial. What is also particularly exciting is the collaborative spirit of this venture, which is rare to encounter in a field notorious for operating within disciplinary and institutional silos. This joint project between two prominent design studios and four individuals based across four cities, both in Pakistan and abroad, creates new local models for collaborative spatial practice.

Perhaps most inspiring of all is the team’s persistence in the face of multiple obstacles, as well as the total absence of support from any institution or governmental body. The Pakistani arts funding landscape is particularly bleak. Financial sponsorship for independently-led projects is not only hard to secure, but is often tied to one’s proximity to power, social capital and privilege. Similarly, participation processes for events of this nature are entirely unclear, leaving creatives to deal with endless paperwork, bureaucratic hoop-jumping and dead-end conversations with various institutions and individuals. In countries with more robust arts programming, participation and sponsorship at national level is a relatively transparent process led by governmental bodies. In this team’s case, what worked was a combination of tireless fundraising through private networks, and wise decision-making based on certain lessons learnt by members of the Coalesce Design Studio during their first-ever participation in 2018.

The Pakistan Pavilion is a sharp, modest insertion in an otherwise noisy, tech-heavy biennale; it effectively tackles what it sets out to do: drawing attention to the Global North’s role in what we now call the ‘climate crisis’ and insisting that a concerted effort towards global change will come from acknowledging the root of the problem.

Ultimately though, Pakistan’s participation also forces us to reckon with the cost incurred by Global South creatives—financial, emotional and otherwise—of participating in prestigious international exhibitions of this scale, as well as the contradictions embedded within the institutional format of a biennale. For as much as this year’s thematic focus is collective action, relationality and interconnectedness in the face of crisis, the irony is that those without passport privilege will still be queuing at visa centres, spending exorbitant sums on shipping and renting exhibition spaces against devaluing currencies. Unless generously funded and supported by their own governments—which in itself is a tool for cultural diplomacy—most of the Global South will remain under-represented and largely absent from these platforms.

What, then, is to be done? Should we simply push for fairer funding opportunities, state-mandated or otherwise, for the arts in Pakistan, so that we’re able to better represent ourselves on the global stage? Or should we begin to think of other pathways, other futures, beyond the yoke of Western imaginations? I am thinking about Gaza, battered by bombs as I write, where a group of young artists formed a collective called the Gaza Biennale. “No war can stop the dreams of dreamers, and no mechanisms of domination extinguish the light in the hearts and minds of creators” they declare on their website. A fluid, tentacular, itinerant biennale; one that asks for no permissions, courageously circumvents borders and censorship, co-opts and redefines everything the term ‘biennale’ stands for, all the while weaving webs of solidarity with those who question systems that were never meant to work for us.

Perhaps now is the time to actively learn from collectives such as these, and redirect our energies towards dreaming up bolder structures, systems and networks of our own—ones in which we are neither held down by white privilege, censorship and disgruntled visa officers, nor corporate money, art world lobbying and institutional straitjackets.

The 19th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice is open to visitors from 10 May to Sunday 23 November 2025, curated by the architect and engineer Carlo Ratti.