For a country where official business is still conducted via stacks of drawstring-bound files shuffling from one bureaucrat’s desk to another’s, the Pakistani government’s embrace of information technology as a panacea for governance failures is a bit ironic. Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif envisions an e-governance system where federal ministries operate in a paperless environment and cater to citizens through digital service delivery. This initiative, we are told, will be transformative for government efficiency and citizen well-being. Underlying this tech utopianism, however, is a fundamental lack of understanding of how information technology systems work and benefit us.

The Prime Minister is not wrong to want better services—he's wrong about the prescription. Technology amplifies capacity; it cannot create it. A dysfunctional bureaucracy with an app is still a dysfunctional bureaucracy. Put differently, government officers who are unable or unwilling to help citizens who show up in person seeking government services, are arguably unlikely to be helpful when those same services are requisitioned through an app.

The proliferation of information technology has undeniably reshaped the way we work. Software tools have turbocharged productivity, turning tasks that once took weeks into minutes. Communication tools have rewired human connectivity, obviating the need for physical, in-person interaction for routine government services. It is easy to see why government officials in Pakistan have such faith in IT oriented solutions for every problem.

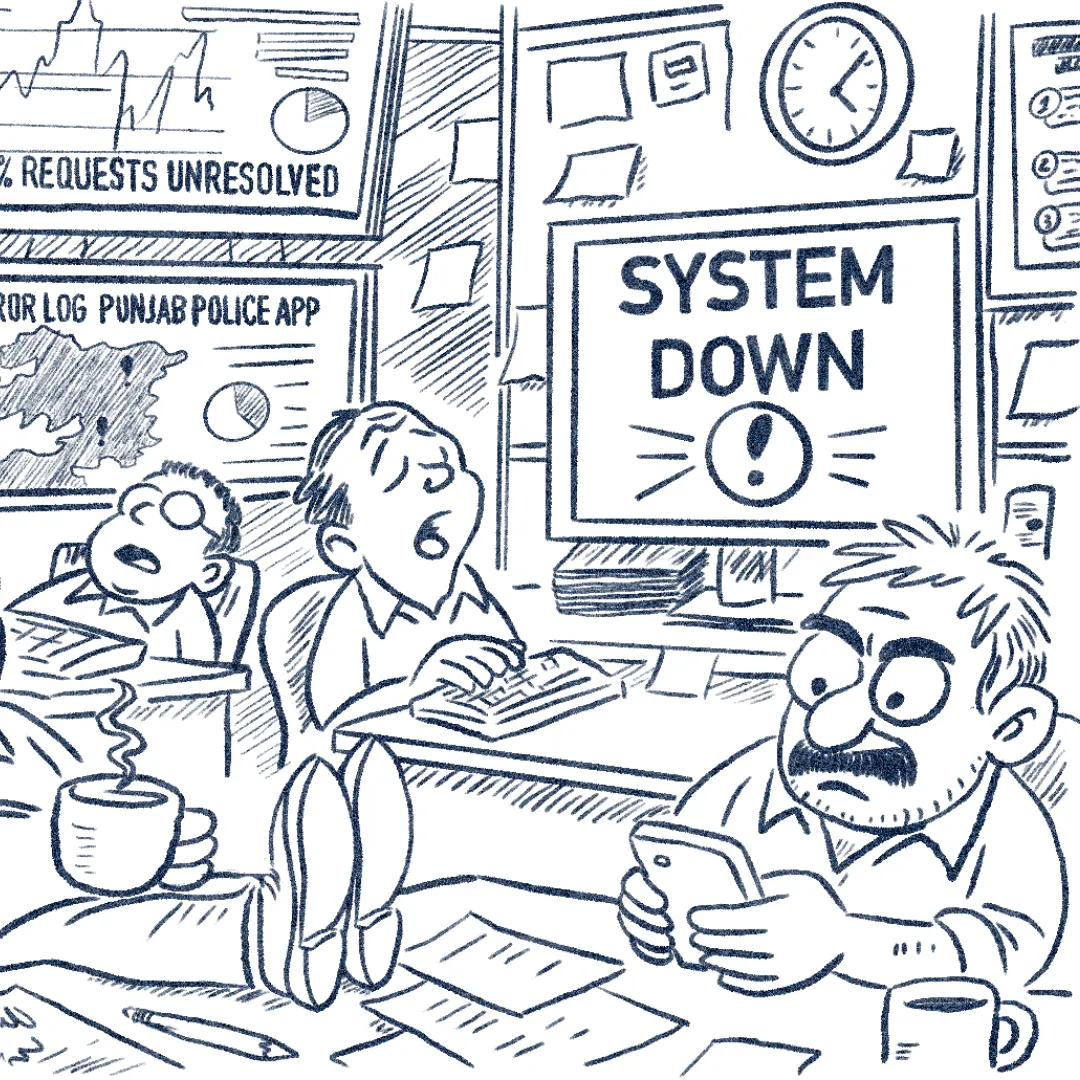

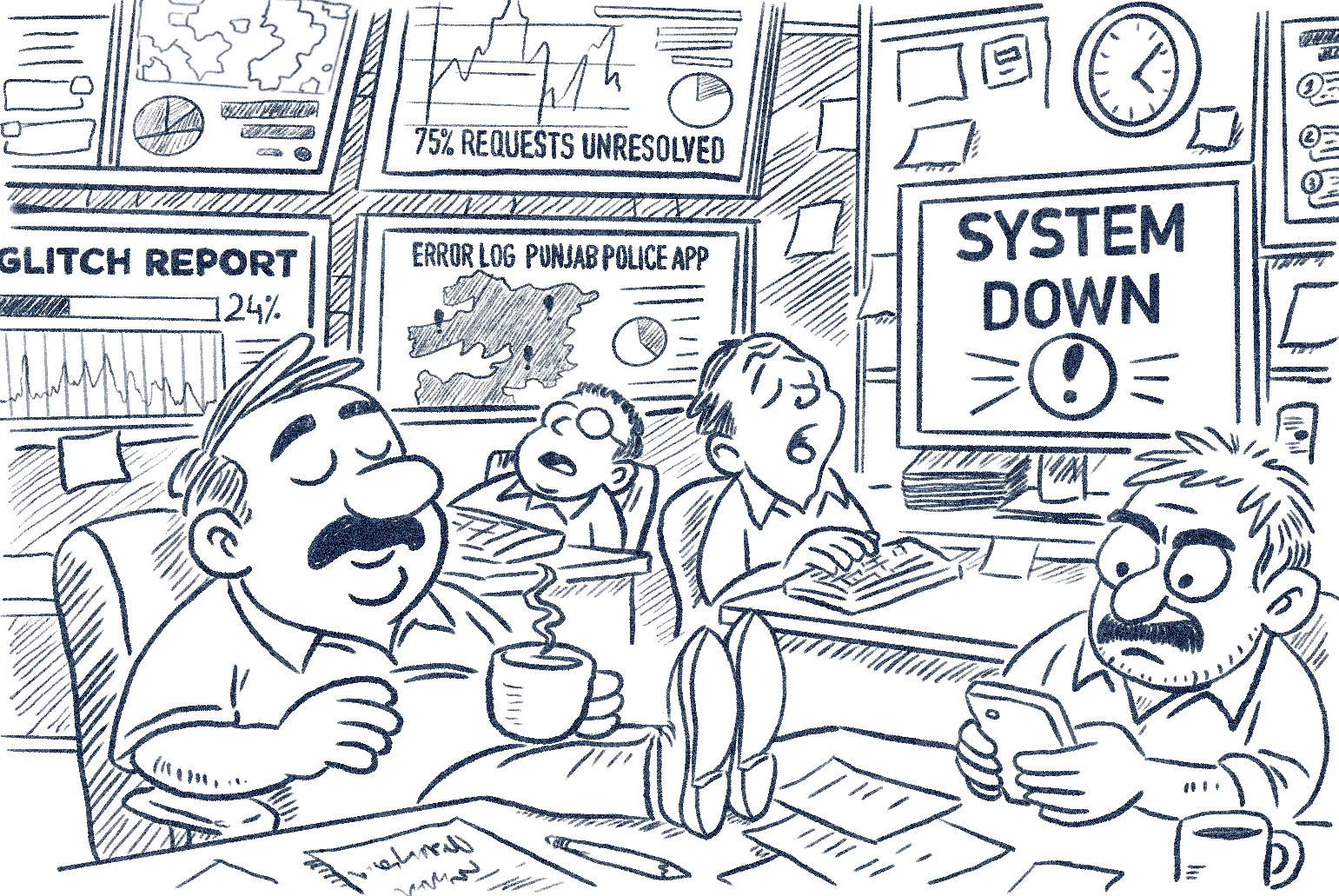

A dysfunctional bureaucracy with an app is still a dysfunctional bureaucracy. Put differently, government officers who are unable or unwilling to help citizens who show up in person seeking government services, are arguably unlikely to be helpful when those same services are requisitioned through an app.

Bureaucratic inertia? A custom software system will increase efficiency. Poor service delivery? Reroute citizens to online channels. Lack of transparency? Set up a control room. Nearly every governance and administrative failure—from poor public education to tax collection challenges—is met with an appeal to some kind of technological solution, as if websites and software systems will compensate for the systemic apathy that permeates the Secretariat.

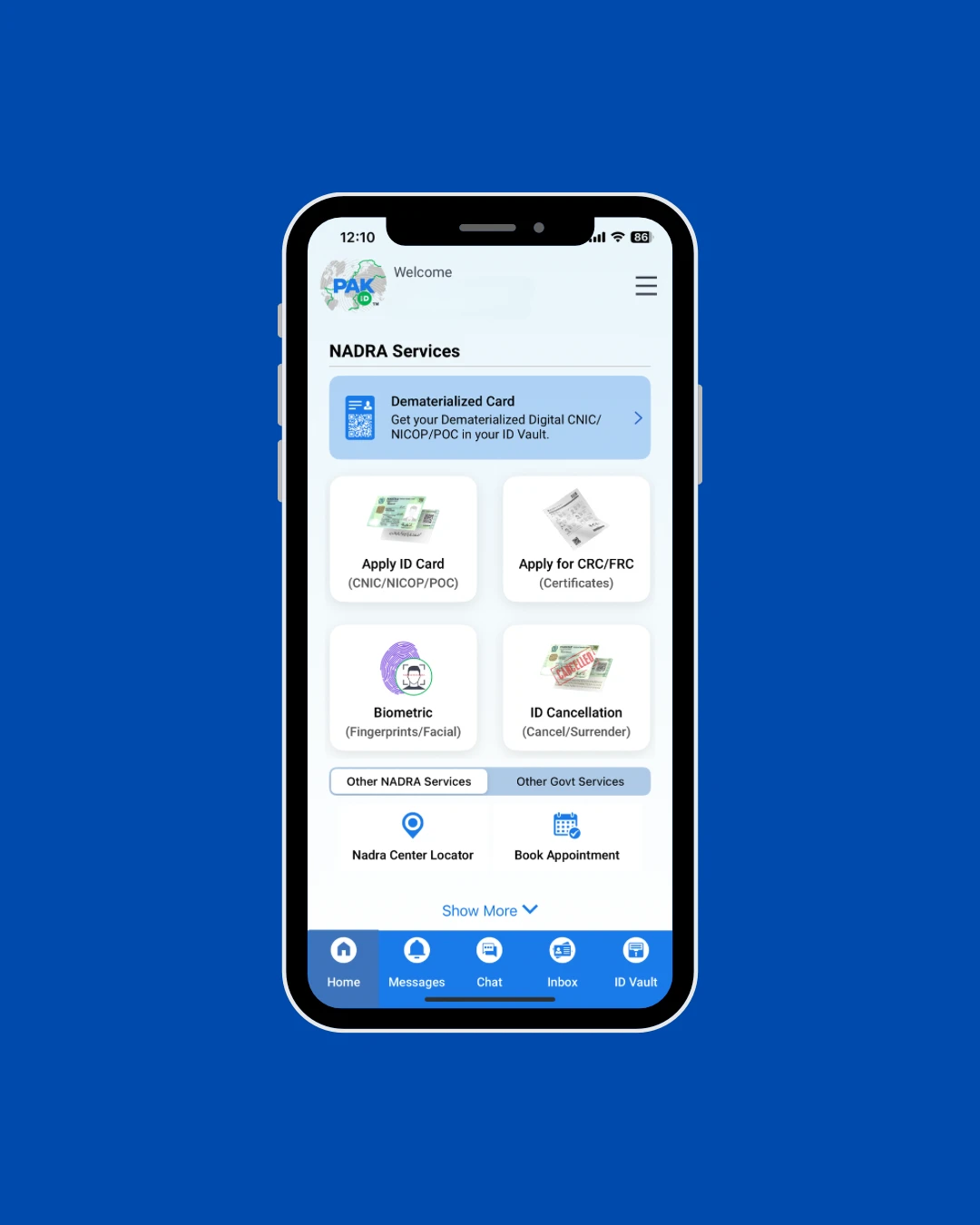

Yet, government departments seem convinced that they are only ever an Android app shy of Singapore levels of service excellence. The Google Play store hosts roughly 200 apps from different government departments in Pakistan, purportedly to offer citizens a convenient new channel through which to requisition government services.

It is debatable, though, whether these apps are actually convenient to use. No more than a third of the adult population in Pakistan demonstrates comfort using relatively complex mobile apps. Among over-18s, less than half use any form of social media and only a third use Whatsapp. And government apps are nowhere near as easy to use as Whatsapp—only 5 of the 100 apps produced by PITB score 4 stars or more in user reviews. It is baffling why the government is bent on making mobile apps the primary interface for citizens when the vast majority of the population needs help using them.

Admittedly, Pakistan has a large population and government departments deal with large volumes of requests. This is precisely the sort of problem where technology is best applied, with remote service options and self-service channels reducing congestion and queues in government offices. But Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments collectively employ more than 3.2 million individuals. This is a third of the country’s formal labor force. The one thing the government should be able to do well is provide good, helpful in-person service, instead of redirecting citizens to a mobile app.

The taxpayer money spent on building these apps cannot be justified on grounds of utility either. NADRA’s Pak Identity app, for example, exists solely for those infrequent occasions when one needs to renew or replace their CNIC. Other government issued apps vary from being useless (such as the contraception guidance app published by Population Welfare Department) to absurd (as is the case for the Meri Awaz women’s safety app, which requires two factor authentication just for the user to log in and press a panic button that will alert ‘concerned authorities’). With just slightly over 500 downloads, one wonders if it has been used enough for the police to have staffed anyone at the receiving end.

The recipe for efficient delivery of government services contains no lines of code.

Experience with the Punjab Police app doesn’t inspire much confidence on this front either. This app has the potential to offer genuinely useful services—like enabling citizens to file a complaint, report a crime, or request a character certificate—if it works. Unsurprisingly, one cannot actually report a crime or receive a character certificate through the app alone: appearing in person at a police station is still required.

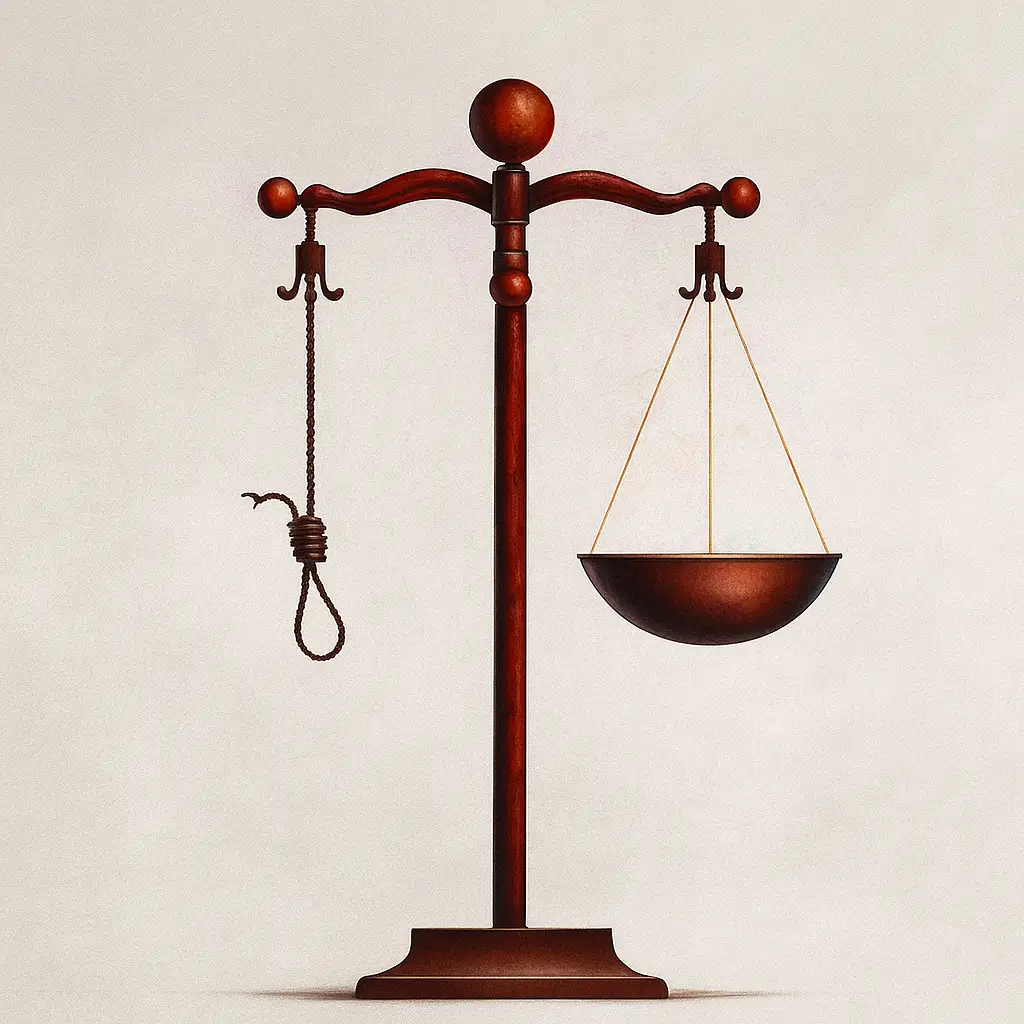

The advent of generative artificial intelligence will undoubtedly unleash renewed enthusiasm for tech solutions. Senior judges have recently suggested that courts could think about utilizing AI to reduce the case pendency rate. With about 4000 judges for a population of 250 million, this is a reasonable suggestion. But anyone who has suffered frequent adjournments in courts or shown up only to find the district judge absent, knows that the justice system is operating far from optimal capacity. So is the case with nearly every other government department, from healthcare to law enforcement. There are certainly capacity limitations within the government, especially in delivering services that require high skill and complex knowledge, but no one is working at peak capacity either. This needs to be addressed first.

The recipe for efficient delivery of government services contains no lines of code. It requires three things: firstly, simple and clearly communicated processes and timelines that both citizens and government officers can follow; secondly, government personnel properly trained to do their job; and lastly, the desire to actually be of help. This can be managed with the right incentives in the form of supervision and periodic performance checks. Until Pakistan fixes these fundamentals, no amount of apps will transform a system where judges skip hearings and apps still require in-person visits. Technology works when it removes friction—not when it is used as a distraction from institutional failure.

* Notes:

- Digital 2024 - Pakistan (https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-pakistan) "54.38 million users aged 18 and above using social media in Pakistan at the start of 2024, which was equivalent to 38.9 percent of the total population aged 18 and above at that time." (Tiktok: 54m (38%); Facebook 44m users (30%), Instagram 17m (12%), Linkedin 12m (8%);

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/whatsapp-users-by-country Pakistan: 51m (36% of adult population);

- ADB Basic Statistics 2024: 21% of Pakistan adults age 15 or older have an active account with a bank or mobile money provider;

- Data on apps compiled from manual search of all government apps on Google Play store and cross-verified with an earlier publication by Digital Rights Foundation https://digitalrightsfoundation.pk/database-of-public-facing-apps-by-the-public-sector/