The kitchen begins its song with the crackle of butter in the pan. Meatballs rendered in lamb fat, grounded in the ancient warmth of allspice, sizzle before simmering in a crimson pool of pomegranate molasses and sour cherries. It is a meeting of opposites — earthy and sweet, sharp and deep — held in careful balance.

As you move through the room, the sharp freshness of parsley and mint rises into the air, bruised beneath a chef’s blade. Garlic and sumac drift past, while citrus brightens a pool of olive oil. Toasted pita absorbs meat juices; golden pine nuts add their final crunch. To stand in such a kitchen is to experience time layered rather than linear.

This is the world Anissa Helou constructs.

Helou creates more than recipes; she builds culinary history through lived experience. Her work stretches from Beirut’s sunlit kitchens to the markets of the wider Mediterranean and across what she calls the Islamic culinary world. A geography shaped by empire, migration, trade and faith.

Born in Beirut with Syrian heritage, Helou left Lebanon at twenty-one, two years before civil war erupted. Her departure, sparked by intellectual restlessness and a fascination with French existentialism, became a permanent exile when war made return impossible. Before she ever wrote a cookbook, she worked at Sotheby’s and later as a consultant in Islamic art, curating collections for prominent Gulf families. That curatorial discipline — the instinct to preserve, contextualise and interpret — would later define her culinary scholarship.

What distinguishes Helou’s work is her refusal to treat cuisine as static or ‘pure’. Instead, she reveals it as layered. Persian court refinement flowed into Abbasid Baghdad; the Ottoman administration absorbed and redistributed flavours across three continents; Mughal kitchens in South Asia adapted Central Asian and Persian traditions to local climates and ingredients. Culinary influence, she shows, moves along the same routes as power and migration.

Helou did not publish her first cookbook until her forties. Yet, she approached food as she once approached art: as a cultural artefact. A recipe, in her hands, is not simply instruction. It is evidence: of migration, of adaptation, of survival.

Her landmark work, Feast: Food of the Islamic World, maps culinary traditions from Persia and the Levant to North Africa, Anatolia and Mughal India. Drawing on medieval Arabic cookbooks from the Abbasid era, historical Ottoman and Persian culinary traditions, as well as extensive regional fieldwork and domestic kitchens, the book traces how ideas travelled across lands long before modern borders calcified them into nations. The book won the James Beard Award and was named one of the best cookbooks of the twenty-first century by The New Yorker — recognition not merely of its recipes, but of its scholarship.

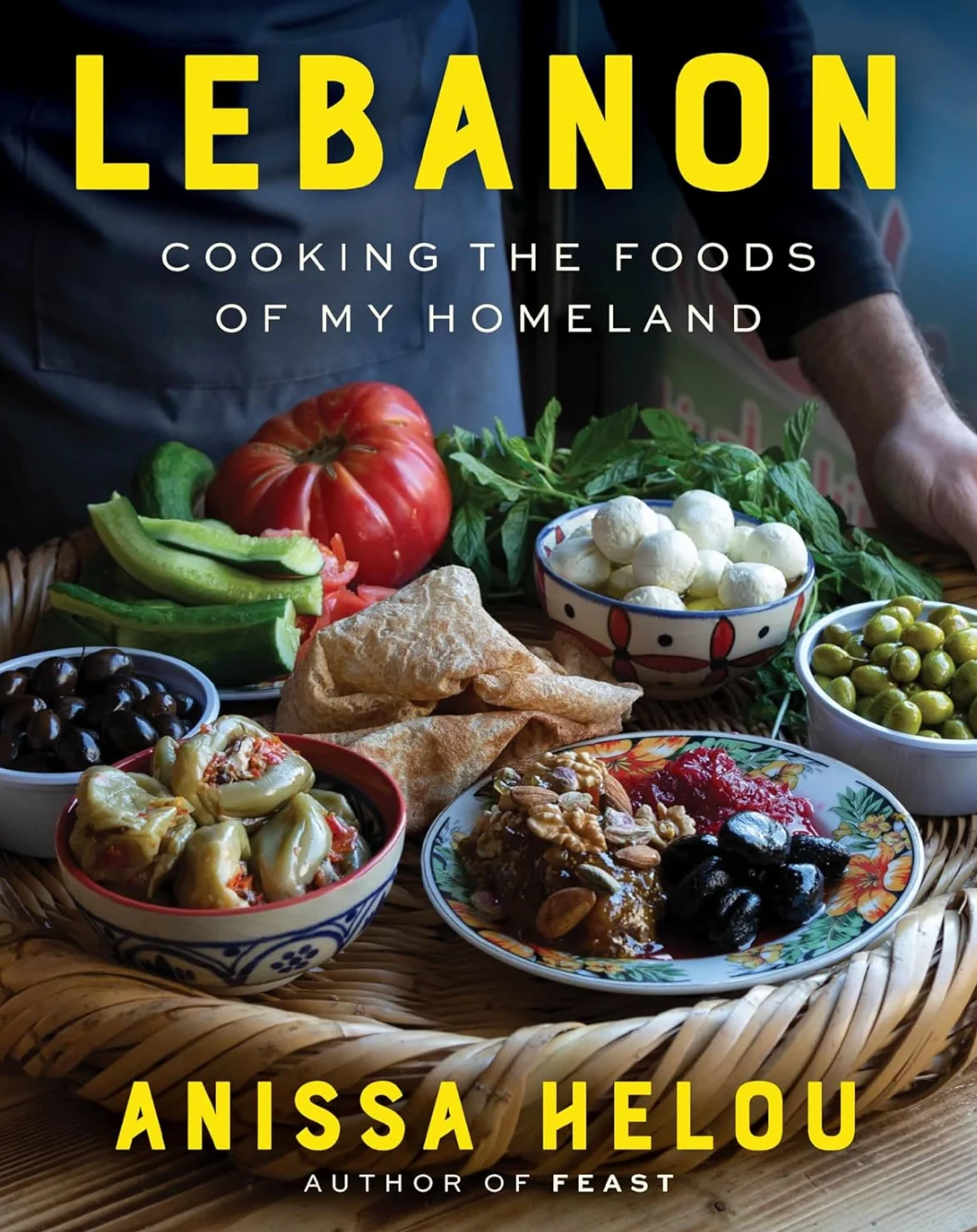

Her latest book, Lebanon: Cooking the Foods of My Homeland, turns inwards. It is at once memoir and archive, a return to her mother’s kitchen and to the culinary language of a homeland fractured by politics yet unified by taste.

What distinguishes Helou’s work is her refusal to treat cuisine as static or ‘pure’. Instead, she reveals it as layered. Persian court refinement flowed into Abbasid Baghdad; the Ottoman administration absorbed and redistributed flavours across three continents; Mughal kitchens in South Asia adapted Central Asian and Persian traditions to local climates and ingredients. Culinary influence, she shows, moves along the same routes as power and migration.

For a reader in Pakistan, this work resonates deeply. It evokes a profound sense of déjà vu. A recognition of our own tables in the distant Levant. We see our samosa in their sambusak; our tandoor culture mirrored in their tabūn ovens; and a shared love of sourness. Where Levantine cooks reach for sumac and pomegranate molasses, we find parallel notes in anardana and tamarind.

Even our festive centerpieces echo shared ancestry. A Levantine roast chicken layered with rice and nuts recalls our Afghan-influenced pulao. Both descendants of Persian rice traditions, adapted to local taste, climate and trade. These are not coincidences. They are culinary footprints of empire and exchange.

Helou herself identifies Persian cuisine as a foundational influence. Not in simplistic hierarchy, but in historical reality. The Abbasid Caliphate absorbed Persian courtly sophistication into Baghdad; from there, culinary ideas radiated westward to Ottoman lands and eastward to the Mughal courts. What emerged were not replicas, but adaptations shaped by geography, ingredient availability and local aesthetics.

If borders are recent constructs — and in both Lebanon and Pakistan they are — cuisine predates them. Pakistan, formed in 1947, inherited Persian, Central Asian and Mughal influences layered upon older Indic traditions. Lebanon, shaped by Ottoman rule, French mandate and earlier empires, similarly carries multiple inheritances. No dish exists in isolation.

Helou’s work gently challenges the modern appetite for culinary nationalism. In an era where identity is often asserted through exclusivity, she demonstrates that food resists such rigidity. A dish like mulukhiyah carries traces of Pharaonic Egypt, Levantine adaptation and regional reinterpretation. Similarly, our yakhni pulao or nihari cannot be reduced to a single origin story; they are the product of layered influence.

Her anecdotes illuminate this beautifully. The Fatimid ruler Al-Hakim once banned mulukhiyah, allegedly deeming it aphrodisiacal; the Druze community is said to observe that ban to this day. In India, the exiled Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s constrained kitchen budget is credited with the potato-laden Calcutta biryani. A reminder that even austerity leaves culinary marks. History, whim, exile — all imprint themselves on what we eat.

Helou also underscores the role of ritual. In Lebanon, hrisseh — a slow-cooked wheat-and-meat dish belonging to a wider family that includes harees and South Asian haleem, is prepared by both Christians and Muslim: Christians for the Feast of the Assumption and Muslims during Ashura. The theological meanings differ; the act of slow cooking and communal distribution remains strikingly similar. In Pakistan, haleem occupies a comparable space, appearing at shrines and religious gatherings across sectarian lines.

What persists is not doctrine, but practice. The stirring of wheat and meat for hours; the sharing; the collective labour. Through such dishes, older cultural memory survives beneath newer political divides.

Helou’s career embodies permeability. Having lived in London, Paris and beyond, she writes as both insider and observer. She documents Saudi culinary heritage, explores Mediterranean street food and returns repeatedly to Lebanese domestic kitchens. Her scholarship is not romantic nostalgia; it is deliberate preservation.

Street food tells a parallel story. Lahore’s winding bazaars, thick with the scent of kebabs and bread, find resonance in Beirut’s bustling alleys. Shawarma, now global, began as an Ottoman technique of stacked, vertical roasting. It evolved regionally, then migrated to Europe and the Americas. In Britain, it became the late-night student staple; in Mexico, it inspired tacos al pastor. Culinary borders, unlike political ones, remain porous.

Helou’s career embodies this permeability. Having lived in London, Paris and beyond, she writes as both insider and observer. She documents Saudi culinary heritage, explores Mediterranean street food and returns repeatedly to Lebanese domestic kitchens. Her scholarship is not romantic nostalgia; it is deliberate preservation.

In regions like ours, where war, modernisation and urban redevelopment can erase physical history, one begins to wonder whether taste is a more durable archive than stone. Buildings fall; recipes adapt and survive. A grandmother’s technique travels in memory, not marble.

This may be the quiet power of cuisine: it resists erasure by evolving. It absorbs influence without surrendering identity. It allows borrowing without annihilation. Where politics draws lines, food draws connections.

Helou’s work ultimately argues — implicitly rather than polemically — that survival has always depended on exchange. The shared sourness between sumac and tamarind, the mirrored rice traditions, the common wheat-and-meat ritual of hrisseh and haleem — these suggest a shared civilisational palate shaped less by separation than by centuries of contact.

In an age defined by sharper rhetoric and fortified borders, this insight feels urgent. The dinner table may not dismantle conflict, but it complicates narratives of purity. It reminds us that what we claim as exclusively ours is often the result of mingling.

Helou does not present cuisine as utopia. She presents it as historical testimony; evidence that civilisations speak to one another, that migration leaves flavour behind, that exile transforms taste and that women’s kitchens often preserve what politics forgets.

Perhaps that is why her work feels so resonant in Pakistan. We recognise ourselves in the Levant not because we are identical, but because we share layered histories. Our plates testify to centuries of contact: Persian refinement, Ottoman diffusion, Mughal adaptation, local improvisation.

And in that recognition lies something quietly radical: the understanding that identity need not be rigid to be real.

Ultimately, Helou reminds us that the kitchen is more than a site of sustenance. It is an archive, a map, and occasionally, a form of resistance. Not loud, not militant, but enduring.

All photographs in the text are courtesy of the author; the main header image is from a cover of Feast.