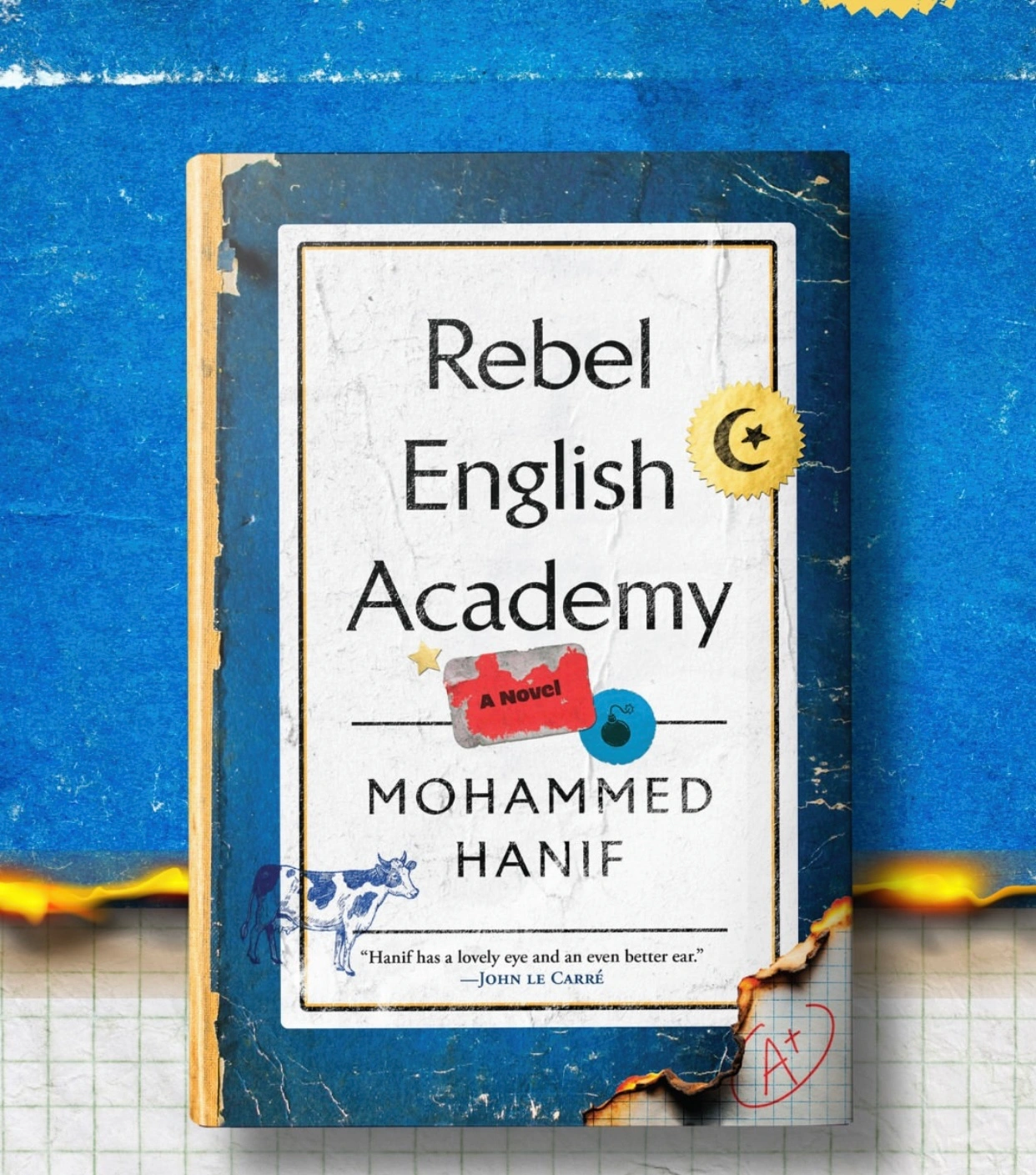

Rebel English Academy (Atlantic Books, 2026) begins on the eve of a famous hanging in Pakistan’s history. It is April 1979, and ‘a very important man’ has been hanged in Rawalpindi. Soon after, the debaucherous Captain Gul is dispatched to OK Town, where rumours abound that Bhutto is still alive, where people are setting themselves on fire to protest the hanging. Gul’s life soon becomes enmeshed with various other characters in town: the godless intellectual Baghi, who runs an English tuition center from within a mosque; Molly, the imam of said mosque; and Sabiha Bano, a girl who shows up at the center with the legs of a runner, a long tongue and a terrible attitude. What will ensue in this B-tier Punjabi city in the aftermath of Larkana’s son meeting Larkana’s soil?

Speaking about the origin of the book at ThinkFest 2026 in Lahore, Mohammed Hanif recalled the silent streets in his hometown on the outskirts of Okara, the day Bhutto was hanged. In this novel, Hanif goes further back in time than he’s gone before — A Case of Exploding Mangoes is set in the late 1980s and the rest of his novels take place in later time periods. Not only that, he also sets the story in a fictionalised Okara, a place he has never visited in fiction before. The small-town, provincial nature of the setting is significant. These are not decision-makers in Lahore or Islamabad we are reading about, nor are they the almost glamourised gangsters of Karachi. These are small, petty people living their daily sorrows and watching in horror and fascination as those prosaic sorrows get muddled with history.

Hanif’s novel will see much richly deserved praise for its dark comedy and bold take on taboo topics, but at the heart of the novel is the same question Hanif has been asking since Mangoes burst on to the world stage in 2008: how does one describe and index grief, without letting grief run the show? As always, this is Hanif’s show; the world is lucky to see it.

Humnava mein bhi koi gul hoon ke khamosh rahuun.

God is a major concern. One of my dearly held orthodoxies is that to write about a religious people, one must be (or become) a religious person; disaffected curiosity is not enough. It is irrelevant whether Hanif believes in God; the writer of Rebel English Academy does. He believes in a God that has set up a funky experiment for His children and then taken off for a drink. Who is in charge now? What kind of God just takes off? Will He return in a good mood, or will He have had one too many? Every character in the novel grapples with God in their own way. They banter and barter with God, cajole Him, or then complain incessantly to Him.

The Queen never came to Okara, and neither did her English. More than any other Pakistani Anglophone writer, Hanif speaks the language of the mongrel. One hears the constant thrum of Urdu and Punjabi in each one of his novels. In Rebel English Academy, he makes the question of language more explicit. The central conceit, after all, is an academy that teaches basic English to small-towners looking to improve their chances of employment. Instead of digging into tired questions of linguistic loyalties and purities, Rebel English Academy shows us the middle-class hustler’s approach to language. Baghi, the godless English teacher, tells his students, “When you go to a court and ask for justice, what language do you ask in? Your lawbooks are not written in Arabic. When you apply for a job, you I-remain-your-humble-servant in English. If you get that job, your appointment letter, the terms of your employment are all in English. When you apply for that sick leave, you lie in English; when they throw you out, your termination letter will be in English. I didn’t design this system. I am just preparing you for it.”

Hanif’s novel will see much richly deserved praise for its dark comedy and bold take on taboo topics, but at the heart of the novel is the same question Hanif has been asking since Mangoes burst on to the world stage in 2008: how does one describe and index grief, without letting grief run the show? As always, this is Hanif’s show; the world is lucky to see it.

Questions of heritage and continuity have little place at Rebel English Academy, where students are busy soaking in every word of English they can, to conjure up the miracle of social mobility. The passages told from the character Sabiha’s perspective are particularly fascinating. Written in the form of homework for English class, they depict the achingly flowery composition style that many of us were taught in schools. The first one begins, “Our English tutor Salim Ahmed Salim alias Sir Baghi has tasked me to write an essay about our cow. I can’t write that the cow is Allah’s splendorous creation because Sir doesn’t believe in the existence of Almighty and His numerous manifestations. Although he knows and has taught us very many muscular words of English lingua franca he doesn’t know zilch about cow.”

Perhaps this is how the colonised lash back — by using these muscular words to such catastrophic effect that the coloniser ends up regretting the day they taught English to the Indians.

The plot is propulsive, full of deep kinetic forces pushing every character towards the worst decision imaginable. The wit sparkles, as always, and the one-liners are brilliant. Yet, what has stayed with me, long after finishing the book, is the fact that once again, Mohammed Hanif has taken our history, the rickety treehouse that is our nationhood, and, without ever ignoring the fractures, made it beautiful.