From at least the early 19th century, South Asian ayahs (nurses and ladies’ maids) were hired to accompany British families on ocean journeys between India and Britain. These contracts were often only for one leg of the journey, with the ayahs having to find new employment for their way back to India. In the 1870s, a boarding house called the ‘The Ayahs’ Home’ opened in Aldgate, London, which lodged and found employment for ayahs. By 1897, the Home was taken over by the London City Mission (LCM) and moved to Hackney in 1900.

I was intrigued to find that the Ayahs’ Home was founded in response to a gap created by the “gendered non-intervention” of the British government in cases of abandoned ayahs. Under the LCM administration, the Home became closely linked to the India Office, acting as its quasi-official domestic branch by taking in indigent South Asian ayahs. It also became a site for Christian proselytising. Analysing representations of the Ayahs’ Home further allowed me to explore how they were racialised and gendered as superior caregivers for children, yet at the same time cast as morally and intellectually inferior in an effort to advertise them as capable yet non-threatening employees to potential British employers, upon whose patronage the Home was financially dependent. While there has been significant research on ayahs in colonial India, there is very limited literature on ‘travelling ayahs’. Historical research on travelling ayahs was pioneered by Rozina Visram. She showed that by the late 18th century, ‘black servants’ had become fashionable in Britain due to cheap labour, fondness for an old servant, or as status symbols.

Discussing travelling ayahs, she notes: “they were the most valuable adjunct to the whole life style [sic] of the Raj” and “were considered indispensable for the long voyage home.” She shows how, in 1825, a boarding house called the Ayahs Home opened in London to house stranded ayahs awaiting employment for their return journeys.

The history of travelling ayahs is inextricably linked with British imperialism. The development of their profession and the spaces constructed to accommodate them all reflected imperial discourses of power, race, and gender. These developments, intended to mitigate the anxieties the ayahs’ presence produced in colonisers, coloured their transient spatial experiences. Using advertisements, articles, and photographs from historical newspapers and the London City Mission Magazine (LCMM), I discovered how the locations, reasons for founding, and business operations of the Ayahs’ Home reflected racist imperial attitudes that had developed in the colonies and how they were embodied in the relationships between ayahs and their British employers (who travelled to Britain with them).

Travelling ayahs have appeared in more historical research in the past five years. Historian Olivia Robinson, expanding on the works of historian and anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler and geographer Alison Blunt, uses ship passenger lists and plans, and the LCMM’s articles to study travelling ayahs. She attends to architectural aspects of their experiences in the colony, at sea, and in the metropole, discussing how imperial domestic discourses on race manifest through the physical separation of the ayahs from their white employers in colonial homes and aboard ships—and being infantilised at the Ayahs’ Home.

The Ayahs’ Home was founded in response to a gap created by the “gendered non-intervention” of the British government in cases of abandoned ayahs. Under the LCM administration, the Home became closely linked to the India Office, acting as its quasi-official domestic branch by taking in indigent South Asian ayahs. It also became a site for Christian proselytising.

Ayahs had been coming to Britain since at least the 18th century, their numbers increasing with the expansion of British imperialism in India. These ayahs were hired to attend to British families on their long and arduous voyages back to Britain. While some stayed on with the families to work with them, many were hired only for the journey and then expected to return to India with another family. Ayahs hired for journeys were either recruited by Anglo-Indian families from within the household staff or they would “[engage] the services of an experienced travelling nurse.”

In my research, travelling ayahs started appearing in newspapers from early 1827 onwards, often in advertisements by British people seeking families headed to India to employ their ayahs who wished to return home. The profession is likely much older, as in 1825, the Morning Herald reported a complaint lodged by an ayah against her employers in a Court of Common Pleas, where she claimed “that [this] was her fifth voyage to England.”

In the late 19th century, British women and children began travelling much more frequently along with their ayahs. With improvements in ship technology and the opening of the Suez Canal came an increase in travel between colony and metropole by British women, their children, and their ayahs. Homeward Mail, from its inception in 1857, regularly published lists of ‘Arrivals of Passengers’ in Britain with every listing mentioning multiple ayahs on board.8 With the increased volume of travel, a formal infrastructure for the hiring of travelling ayahs developed. In 1873, a shipping company called Geo. W. Wheatley and Co., with offices in London, Liverpool, and Bombay, advertised that amongst its other services, it also engaged ayahs.

Upon reaching shore in London, ayahs frequently found themselves waiting for journeys back to their homes. Here, the Ayahs’ Home came into play. Although imagined as a benevolent enterprise meant to alleviate the difficulties these transient care workers would have to contend with, it ultimately became a means of profiting off the precarious situation ayahs found themselves in.

In a 1922 LCMM article, travelling ayahs were described as a “strange group of clannish women that a far-flung Empire and our innate lust for wandering have brought into being as a class.” This statement succinctly shows how British imperialism led to the development of the profession of the travelling ayah, becoming more prominent as the empire expanded, simultaneously developing formal infrastructure to make these services more accessible to Britons, such as shipping agents.

Upon reaching the ships at port, the LCMM notes that: “the ayah is at once on familiar ground... she knows the ins and outs of the floating leviathan, and can suggest many matters for the personal comfort of her mistress and the infant’s well-being.” Despite frequent travel by both the memsahib and the ayah, this article construes the latter as more acquainted with the ship, its spaces, and functioning, expected to take charge on it, while the memsahib was not expected to know any of these details or even to supervise the activities. Here, too, ayahs are servants expected to relieve their employers of any physical exertion.

Once onboard the ship, Robinson notes, “the physical distancing of the ayah in relation to the family was immediate.”According to a 1922 article in the LCMM, “strictly speaking, an ayah travels only as a deck passenger,” spending the month-long journey by steamship (or several months in sailing vessels), sleeping exposed to the elements on the ship’s deck on the bedding they brought with them. The inhumane conditions ayahs were subjected to, including sleeping on the deck, were construed as a positive, something “not to be despised on the sultriest sections of the journey.” In some cases, it notes “by arrangement with the chief stewardess, the mistress may be able to have the ayah sleep in the passageway outside the cabin, in a corner of her employer’s private room if she has one, or if there is space, in the children’s nursery.”

Robinson also writes that white servants never experienced these conditions, usually travelling on second class tickets. The spatial segregation of Indian ayahs from the families they were employed to serve was not just upheld by the employers, but the steamship companies themselves, as according to Robinson, rules for four major Suez-route companies in 1913 stated that “Servants and Ayahs... are permitted to be in their masters’ or mistresses’ cabins only while performing their duties.”

In a 1922 LCMM article, travelling ayahs were described as a “strange group of clannish women that a far-flung Empire and our innate lust for wandering have brought into being as a class.” This statement succinctly shows how British imperialism led to the development of the profession of the travelling ayah.

In an 1862 letter published in the Daily News, passengers aboard the steamship The Ceylon wrote to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) about “some great faults in their otherwise well managed vessels, complaining that their ships were overcrowded, with ladies’ cabins having at least three women, as well as children and black ayahs sleeping on the floor;” they further complained of the lack of a segregated saloon for second class women passengers.

Interestingly, while they complain of overcrowding in ladies cabins, partially due to “black ayahs sleeping on their floors,” they do not ask the company to provide the ayahs a separate space; instead, they ask only that “in no case should one lady’s berth be over another, and that there should never be more than two in one cabin.” Similarly, while they protest for a segregated saloon for second class ‘lady’ passengers, no concern is shown for the ayahs sleeping in unsegregated public areas, like decks and galleries. The deck was also where lascars19 too would often sleep, but for the Britons aboard the ship, the lack of privacy or sex segregation was not a concern when it came to working class Indians.

Imperial discourses of racial differentiation were reiterated onboard ships as they were in the colony, while white upper class employers and working class servants were afforded privacy and luxury, the Indian working class was relegated to sleep on public spaces such as the deck. Class dynamics were also instituted to keep working class people, both ayahs and white servants, away from their employers’ cabins.

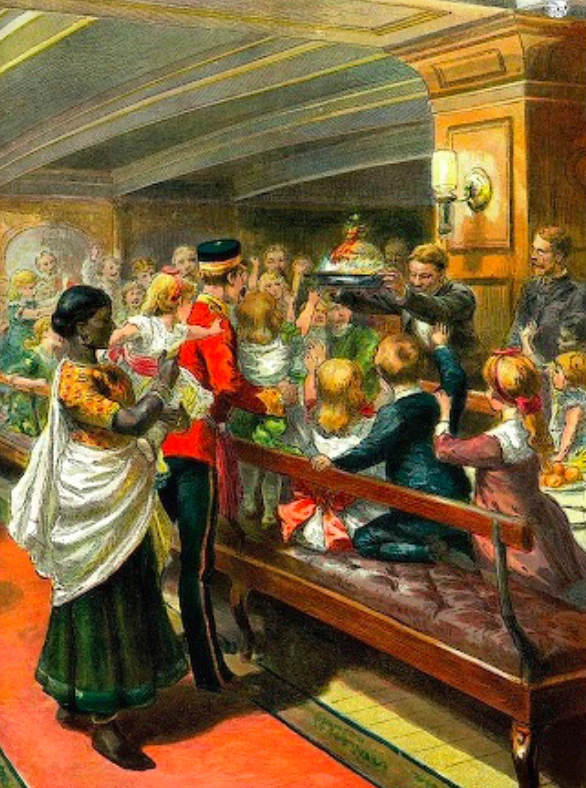

In representations of life aboard ships, travelling ayahs always appear associated with the ship’s deck, and occasionally other public spaces, usually with their charges. An illustration from an 1875 issue of The Graphic shows an ayah seated on the steps of a saloon, holding a white child and, according to the accompanying description, “humouring every fancy and whim which the baby displays, and if it is an Indian baby there is no end to its fancies and whims.” Similarly, an illustration from an 1880 issue titled ‘A Study in Black and White’ shows a white child standing next to his ayah sitting on the floor of the deck, described as “a startling contrast in colour between a fair-haired young Saxon and a dusky ayah, who as a rule ruins her young charge by the most absolute devotion to his every wish and whim.”

Another image, from an article titled ‘Homeward Bound from India’, depicts Anglo-Indians playing roughly all over the deck, disrupting the siesta being taken by adults.21 In this image, surrounded by children climbing things, playing games with one another, and adults lounging on deck chairs, a lone ayah sits with a child on the floor. These illustrations all place the ayahs on the decks of the ship, seated on the floor, denied the option of sitting on chairs like white adults. These images, along their descriptions, reproduce the discourses found in household manuals of Anglo-Indian children being spoilt at the hands of their weak-willed and affectionate Indian servants, reiterating the detrimental effect they had on their charges. At the same time, however, these images also sentimentalise the relationship between them, a representation that some scholars have argued helped naturalise the role of ayahs as gendered and racialised caregivers.

The limited documentation on travelling ayahs leaves many unexplored avenues for research, particularly from a historical perspective. Studies have mostly focused on the question of their agency, with little attention paid to the Ayahs’ Home itself. The Ayahs’ Home’s connections with the LCM, and consequently British imperialism, requires more attention. Furthermore, the Ayahs’ Home as a site for the reproduction of imperial discourse also requires further analysis.

In 1941, the LCMM reported that the LCM’s work among foreigners and Jews had been curtailed, but not stopped, due to the war, although, it said “only one department has been temporarily closed, namely, the Home for Ayahs and Amahs, at Hackney.” The article explained that it had been turned into a “hostel for bombed-out families” and suggested that this arrangement was for a short duration as it hoped “for the early resumption of the splendid work among oriental nurses, for which Mr and Mrs William Fletcher have been so long responsible.” The Ayahs’ Home would not open again, and in May 1952, the Ayahs’ Home’s account at Barclays Bank was closed, marking the complete end of the institution.

Although the profession of the travelling ayah had existed since the early 19th century, it developed rapidly in the aftermath of an event that engendered an existential imperial anxiety: the Great Rebellion of 1857. The untouchability of colonisers, and the imperial project itself, was brought into question and although colonialism emerged from it stronger than ever, it made a lasting impact on the way the colonists viewed their subjugated peoples. Imperial anxieties centring on domestic servants crept into the domestic sphere. As white women became settlers in the colony, supporting the imperial project by maintaining imperial domesticity, their protection was held up as the impetus for sharpening racial boundaries.

The paradoxical representation of the position colonial servants, like ayahs, held in the colonial house is best described by Stoler as “both devotional and devious, trustworthy and lascivious.” Domesticated as an imperial necessity, yet feared for their intimate proximity to the Anglo-Indian family and the “pernicious control” they had in domestic affairs. Imperial power was asserted through infantilising them, treating them as no more than the children they were responsible for. To escape these unfavourable influences, Anglo-Indian children were sent back to Britain to develop metropolitan sensibilities.

The limited documentation on travelling ayahs leaves many unexplored avenues for research, particularly from a historical perspective.

In my dissertation and my research, I have charted the development of the Ayahs’ Home from its time as a private, purely entrepreneurial business, to its acquisition by the London City Mission, turning it into a quasi-official institution. I have argued that the Ayahs’ Home was a complicated space that, like the colonial home, reproduced, and maintained imperial power. Imperial power was expressed through both the functioning of the Ayahs’ Home as an institution that, in the absence of state intervention, took on its role in providing shelter and employment to the ayahs who travelled to Britain, as well as its publications which reproduced discourses on race and gender that were integral to imperial power.

This essay was first published in The Aleph Review, Vol. 8 (2023). Adapted by Hassan Tahir Latif from a master’s dissertation titled The Ayahs’ Home at Hackney: Race, Gender and Empire 1855-1941, submitted at University College London, Bartlett School of Architecture. Please reach out to the author for a bibliography.