For those familiar with Lahore’s literary topography, names such as ‘Readings’, ‘Variety’, ‘Liberty’ and more recently ‘The Last Word’ are enough to evoke the scent of fresh paper and binding glue; these are places where many have communed with books and found their love for literature. There are also the occasional book launches hosted at Alhamra during literary festivals, which allow a space for readers to access literature and literary conversations. However, one space exists outside these institutionalised spheres of literature in the city and endures despite all odds.

Early every Sunday, booksellers begin to set up outside the colonial-era facades along The Mall, aptly positioned in front of the Pak Tea House. The footpaths, and sometimes even the inner crevices of Anarkali Bazaar itself, transform into a living archive. Unlike increasingly digitised and commercial literary environments, this weekly market, popularly known as the Anarkali Sunday Book Bazaar, operates at the intersection of affordability, spatial memory and informal circulation, suggesting that literary consumption in metropolitan Pakistan cannot be understood solely through formal institutions or elite spaces. Reading inaccessible classical texts does not necessitate that you have access to thousands of rupees in your pockets, or to even a literature classroom. Here, though, you can simply pick up literature off the footpath.

A central argument in contemporary sociological studies of consumption is that informal markets often sustain practices made invisible or inaccessible by formal economies. In the case of the Sunday Book Bazaar, this includes forms of analogue reading that are increasingly marginalised by digital learning systems and generative AI technologies. As recent trends depict, the expansion of AI-driven summarisation and content delivery has compressed the temporal and cognitive space for deep reading. However, almost as if in response, the Bazaar’s slow, uncurated browsing model becomes a medium of resistance, particularly for students, low-income readers and those pursuing knowledge outside formal institutions.

On my most recent visit to the Bazaar, while I was browsing through the stacks (some on carts, others laid out on plastic sheets on the ground), one seller who was just setting up his display, initiated a conversation about pricing and the value of books. I had not been paying attention to the customers around me, but his tone turned reflective as he asked, almost rhetorically, why people still felt the need to bargain when he was selling a book for just 200 rupees. Barely a dollar in current exchange rates. He then added, almost dismissively, “Lekin humein itna farq nahi padta” (it doesn’t bother us so much) before noting, “Kam se kam kitab khareed to rahe hain” (at least they’re buying the books). He completely caught me off guard, as he posited that the price customers pay for a book does not even come close to the expansive knowledge it offers in return. For him, the fact that people are still buying books, regardless of the price point, was perhaps more important than the negotiation itself. His comments reflected a broader concern: that book purchasing, and perhaps reading itself, has seen a noticeable decline in recent years.

The expansion of AI-driven summarisation and content delivery has compressed the temporal and cognitive space for deep reading. However, almost as if in response, the Bazaar’s slow, uncurated browsing model becomes a medium of resistance, particularly for students, low-income readers and those pursuing knowledge outside formal institutions.

The Sunday Book Bazaar is more than just a shopping site — it is a sensory archive. Early in the morning, one finds vendors unpacking tattered cartons of books under rusting tents, wiping dust off old Urdu digests, translated Russian novels and pirated editions of a myriad self-help books. Many have dedicated spaces that they return to Sunday after Sunday. One stall owner, Ghulam Rasool, a bookseller for over three decades, recounts that he once sold a rare copy of Das Kapital to a lawyer who then returned the next week with photocopies to redistribute to others. These small moments mark the Bazaar not simply as a site of exchange, but of re-circulation and recontextualisation.

The Sunday Book Bazaar's horizontal, non-commercial structure stands in contrast to privatised knowledge economies that dominate educational publishing and retail. A student can buy translated political theory or literary fiction at a fraction of formal retail prices. This informal infrastructure not only addresses market failure but actively challenges the classed boundaries of knowledge access. Which is why it is not uncommon, in fact, for regular visitors to arrive at the Bazaar pulling along empty suitcases. As they move from stall to stall, they methodically fill them with volumes, across genres, disciplines and languages, building personal libraries or collections at a fraction of retail costs. On my most recent visit, I noticed at least two buyers doing exactly that, maneuvering their suitcases between crowds and piles.

This must be located within the broader spatial history of Anarkali, one of Lahore’s oldest continuously active marketplaces. From its Mughal origins to its role as a colonial-era retail hub, Anarkali has long been a site of hybrid social interactions, including trade, politics and cultural life. The Bazaar’s proximity to Pak Tea House, a space central to the Progressive Writers’ Movement, reinforces this legacy. It continues to host an urban counterpublic that is materially and discursively distinct from Lahore’s mall-based bookstores or literary festivals. As Henri Lefebvre (in The Production of Space, 1991) and Edward Soja (in Seeking Spatial Justice, 2010) suggest, space is never neutral, it is produced through power, access and use. The Sunday Book Bazaar, in this sense, exemplifies what spatial theorists call a ‘lived’ or ‘differentiated’ space, operating through informal economies and collective practices that resist top-down planning and exclusionary design.

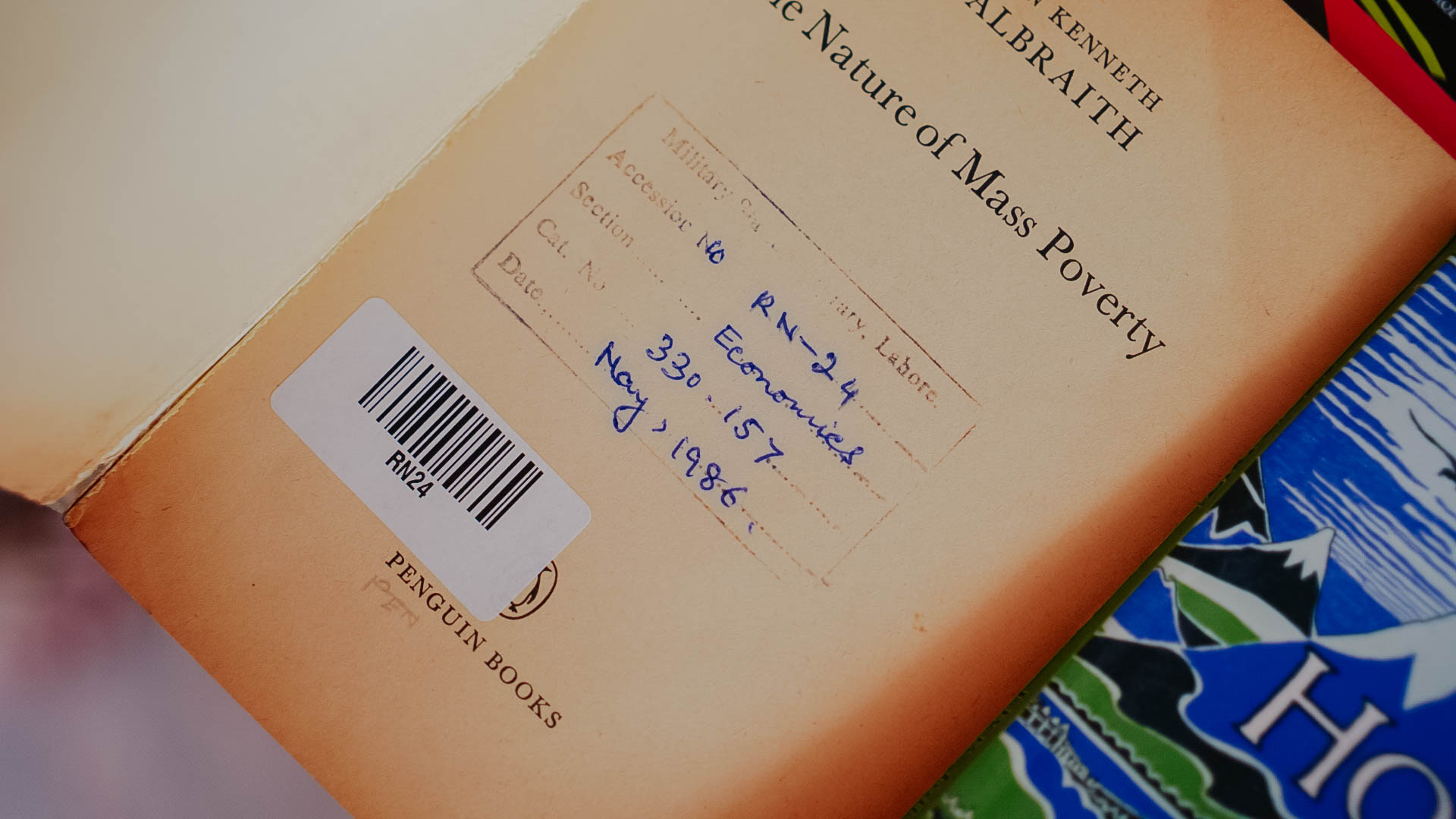

It is worth noting that a common perception among many elite Lahoris, especially those accustomed to curated shopping at high-end commercial plazas, is that items sold on footpaths are either low-quality surplus goods or charity-related commodities (e.g., socks, lighters, or matchboxes). Such goods are often purchased not as necessities, rather as acts of altruism. However, in the case of the Book Bazaar, this assumption rarely holds. The quality and variety of texts on offer rival that of formal retail stores. One can find pristine copies of new novels, academic reference books and literary anthologies laid out in front of decades-old facades of colonial architecture. As for second hand books, the fact that a book has passed through multiple hands enhances its appeal to me personally. Used books offer insight into former readers; their margin notes and underlined passages speak to a shared intellectual lineage.

The Sunday Book Bazaar's horizontal, non-commercial structure stands in contrast to privatised knowledge economies that dominate educational publishing and retail. A student can buy translated political theory or literary fiction at a fraction of formal retail prices.

Yet even more interestingly, the Bazaar’s circulation includes texts that are often subject to formal restrictions, such as politically sensitive memoirs and religious literature. Certain books even on the history of Pakistan, which cannot be found in formal bookstores, have multiple copies available here. In an age of increasing focus on banning films and digital content by institutions such as PEMRA, these books continue to escape such restrictions. The presence of these books in the market underscores how regulatory exclusions are routinely circumvented through informal networks.

The spatial and political implications of such markets are not trivial. They reveal the persistence of public literary culture in a city where public libraries are under-resourced and educational institutions are increasingly oriented toward commercial content delivery. The Bazaar’s continued existence reaffirms the relevance of what Nancy Fraser (in Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy, 1990) describes as subaltern counterpublics — parallel spheres of discourse and exchange that sustain marginalised identities and needs. I do believe that the Bazaar’s informality is not accidental, rather a strategy; an evolving infrastructure that ensures literature remains embedded within the everyday geographies of the city. This endurance is arguably linked to the Bazaar’s makeshift and temporal nature; it does not claim permanent space in Lahore’s high-end commercial zones, but rather appears on Sundays when formal markets are closed. And the Bazaar only attempts to occupy, at most, their footpaths.

Increasingly, every space in Lahore that is not devoted to shopping, food or other contemporary forms of retail finds itself cut down at the hands of the LDA, the Lahore Development Authority. First it was the decades-old nurseries, which have now been transformed into CBD, and more recently, even the pet market. Which is why the Sunday Book Bazaar reflects a collective, low-cost and politically plural reading space that continues to adapt through economic volatility and socio-political constraint.

All photos courtesy of the author.