We live in times when the fever for reading is waning, social media is fracturing attention spans and an AI glut everywhere is making people more passive and reliant on AI-generated content. Other contributing factors include lack of time, mental health challenges (e.g., depression, anxiety), and, among lapsed readers, poor vision or difficult life events. In a country like Pakistan, these issues are further exacerbated by socio-economic hardships.

According to the World Population Review, the top three countries in terms of books read annually and hours spent reading are the United States (17 books, 357 hours), India (16 books, 352 hours) and the United Kingdom (15 books, 343 hours). Pakistan, in contrast, ranks among the lowest three, with only 2.6 books read per person annually and 60 hours spent reading. This lack of reading is so widespread that statistics aren’t even necessary; lived experience speaks louder than any report. Just ask your friends and family when they last read a book from start to finish.

Public libraries, with their accessibility, non-elitist spirit and ability to offer a wide range of books, can serve as a vital counterbalance, nurturing the literary tastes and intellectual curiosity of people from every background. They are especially crucial in a society where many people cannot afford to buy books, lack quiet space at home to read or study and have limited exposure to a broader literary culture. Beyond free access to books, libraries offer quiet study areas, digital resources, community programmes and a sense of shared civic belonging that few other institutions can match.

There are multiple obstacles [in Pakistan] to transforming public libraries into spaces that can foster a sustainable literary ecosystem. The tragedy unfolds on three levels.

In antiquity, archives and libraries were indistinguishable, meaning libraries have existed as long as written records. A temple at Nippur (early 3rd millennium BCE) housed rooms full of clay tablets; similar collections from the 2nd millennium BCE were found at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt. Ashurbanipal (668–c. 627 BCE), the last great Assyrian king, maintained a vast archive of about 25,000 tablets gathered from temples across his realm. These early repositories show the deep historical roots of libraries and their enduring role in connecting us to the literary world.

The literary hue was evident to me personally during my first visit to a public library in 2019: the Shuhada-e-APS Public Library in Saddar, Peshawar, a silver lining in itself. It was there that I discovered Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali — I still vividly remember the thin volume tucked away in the English literature section, a discovery that felt both intimate and transformative for my impending journey as a poet.

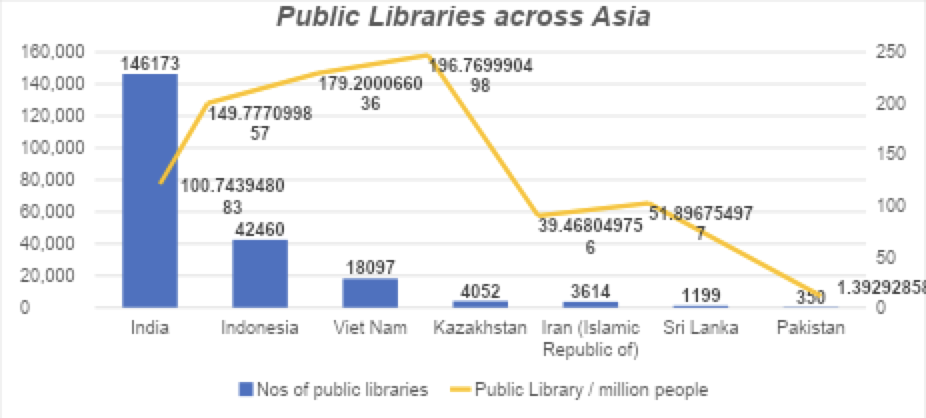

Nonetheless, in this country, the ideal of such literary sanctuaries remains far from reality. There are multiple obstacles to transforming public libraries into spaces that can foster a sustainable literary ecosystem. The tragedy unfolds on three levels. The first is starkly visible: cities either have no public libraries at all, or far too few for the size of their population. A comparison across Asian countries highlights the severity of Pakistan’s library gap and the limited attention it receives from both the government and the public. While many neighboring countries maintain robust public library networks relative to their populations, Pakistan’s coverage remains strikingly low, highlighting the acute deprivation in regions where literary spaces are needed most.

Second, where a library does exist, its infrastructure is often barely functional: dim lighting, broken toilets, and, ironically, a shortage of books. Take, for instance, the Municipal Public Library in Bannu, established in 1905 as the Victoria Memorial Library. It houses a collection of over 5,000 books, periodicals and newspapers on current affairs. Yet, despite repeated requests, it has not received any government-funded renovation and book donations since 2001.

Third, even in places where the buildings and shelves still stand, libraries rarely foster a true culture of reading. Instead of serving as hubs of curiosity and nurturing a sustainable literary ecosystem, they are often filled with anxious aspirants preparing for competitive examinations like the CSS — minds focused on survival rather than exploration. This is hardly surprising in a country where generations have grown up witnessing their parents’ struggles.*

Insecurities born of such uncertainty are often replaced by the pursuit of money, power and social validation. For many, these competitive exams have become symbols of prestige rather than genuine avenues for public service. The aim is not intellectual enrichment but securing a position that carries social capital. Compounding this predicament is an education system that prioritises compliance over innovation, reflecting a lack of national vision. Post-18th Amendment, provincial curriculum development at the primary level has been largely neglected, while higher education focuses on quantitative metrics — new universities and research paper counts — over meaningful learning outcomes. This strained panorama mirrors neoliberal policy priorities, favouring fiscal targets and outputs over human development, and is further compounded by political economy constraints such as fragmented governance and resource allocation driven by political expediency. Funding remains inadequate and often declines in real terms, leaving the system ill-equipped to foster creativity, critical thinking or equitable access to quality education.

Against this structurally skewed backdrop, when schools and universities fail to provide robust curricula or nurture critical thinking and intellectual confidence, students naturally seek alternatives. Libraries, instead of serving as spaces of discovery, often become makeshift training centres — places where students prepare merely to gain the validation and self-esteem that a properly functioning education system should have provided.

On the governance side, several factors contribute to the poor state of libraries. There is no proper planning or national library policy, and no clear framework guiding how public libraries should operate or grow. Libraries are administered by different bodies across provinces, with no unified national library system. Pakistan lacks comprehensive legislation to protect or mandate public library development. The use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) remains weak, with most libraries yet to adopt modern digital systems or online services.

Libraries also lack strategies for public engagement and publicity, limiting their ability to promote services or connect with communities. Professional development for librarians is inadequate, with limited training opportunities, no background in Library and Information Science (LIS), an insufficient career structure and a lack of continuing education programmes, resulting in a workforce ill-equipped to manage libraries or foster a thriving literary culture. Bureaucratic control further hampers progress, as libraries operate under rigid government systems with little autonomy. Other challenges include limited electronic resources, interrupted power supply, low management commitment, insufficient financial resources and low IT awareness among staff. Chronic underfunding and the absence of financial independence leave libraries reliant on small, irregular government budgets.

Libraries also lack strategies for public engagement and publicity, limiting their ability to promote services or connect with communities. Professional development for librarians is inadequate, with limited training opportunities, no background in Library and Information Science (LIS), an insufficient career structure and a lack of continuing education programmes, resulting in a workforce ill-equipped to manage libraries or foster a thriving literary culture.

Addressing the challenges of public libraries in Pakistan requires innovative solutions across short-, medium- and long-term horizons, coupled with a shift in societal attitudes toward learning. Complementing these technical standards, the IFLA/UNESCO Public Library Manifesto (first published in 1949 and most recently updated in 2022) articulates the fundamental missions of public libraries that transcend national boundaries: freedom of access, community development, information provision and fostering democracy and citizenship.

In the short term, libraries can be revitalised with low-cost, high-impact measures: mobile library units reaching underserved communities, pop-up reading corners in public spaces, digital lending via smartphones and interactive workshops for staff and patrons. Incentive-based reading programmes, gamified learning and reading clubs can attract young readers, while designated quiet zones for personal exploration — distinct from exam-focused areas — can help cultivate curiosity. Libraries can also host career guidance sessions, soft skills workshops and book launches to nurture a broader literary and intellectual culture.

In the medium term, structural changes are essential. A national library policy should standardise operations, integrate ICT and digital catalogues and ensure professional development for librarians through training, mentorships and certification programs. Libraries can also evolve into creative hubs with makerspaces, co-working areas and community-driven projects that blend intellectual curiosity with skill-building. Public campaigns, mentorship programmes and partnerships with schools and universities can further encourage diverse learning paths and critical thinking, helping libraries shift from survival-focused study spaces to centres of literary and cultural engagement.

In the long term, libraries should become sustainable literary ecosystems. Financial independence through public-private partnerships or endowment funds can ensure resilience, while nationwide expansion — including mobile and digital libraries — can guarantee equitable access. Education reform must embed critical thinking, research skills and intellectual curiosity in curricula, reducing reliance on rote exam preparation. Leveraging technology — AI-assisted reading recommendations, virtual reality storytelling and digital archives — can offer interactive, personalised experiences, bridging traditional reading with modern learning habits. Together, these measures can transform libraries into spaces that foster a genuine culture of reading, creativity and lifelong learning.

* This makes sense given the context: the macroeconomy itself has remained trapped in cycles of boom and bust, coupled with the abysmal, broken growth model. As the State Bank Governor recently acknowledged, economic growth has been steadily declining — from an average of 3.9% over the last 30 years, to 3.5% over the last 20 years, and 3.4% over the last five years. This has contributed to Pakistan’s current unemployment rate of over 7.1%, one of the highest in 21 years, with over 1 million degree-holders aged 15-29 unemployed. Other disadvantageous economic factors include: decline in real wages, exorbitant inflation, exodus of MNCs and risked investment climate and more.